Staff Sergeant

Albert

S. Brown

Infantrymen

Dull Day

Foreword

Do Something,

Even if it's Wrong

Anzio

Southern France

Colmar Pocket

Germany

Epilogue

Contact Al

dogfacebrownie@gmail.com

![]()

Southern France

Two days before landing in southern France, Third Division soldiers participate in a Mass onboard an LCT

Purple Onion

On August 14, 1944, the day before the Allied landings in Southern France, I was on an LCI (Landing Craft, Infantry) anchored in Corsica harbor. Our craft was part of the huge armada assembling for the invasion the next morning.

An LCI is a small ship and has cooking facilities only for the sailors. Therefore, we were given only the same rations that we have when on the front lines. This did not make us very happy.

The weather was warm and sunny and, in mid-afternoon, some of us decided to go swimming. We would dive in from the ship's railing and climb back up via a rope ladder.

Now, there were many ships in the convoy and they were at anchor all around us. One of the big ships dumped its garbage overboard and the garbage began floating on the tide past our LCI. Well, much of it was not garbage to us. There were whole carrots, potatoes, heads of lettuce and other assorted vegetables in the mix. Some these were not rotted and were without flaws of any kind.

Well, we Doggies had a field day gathering up these prizes to go with our evening rations. I managed to retrieve a huge purple onion that I shared with the men in my machinegun section. We chopped it up and mixed it in our cans of C-Rations. They never tasted so good.

Some of the men made a delicious soup from the assorted vegetables on their one-burner Coleman burners.

It was a day to remember.

D-Day Southern France

August 15, 1944, the Seventh US Army invaded Southern France a few miles east of Marseille and west of Cannes. The Third and 45th U.S. divisions were spearheading the landings.

In our army, infantry soldiers were put ashore mainly in two types of landing craft. One was the LCVP. LCVP stands for: Landing Craft, Vehicles or Personnel. It would transport one jeep with trailer, or, it would accommodate about forty soldiers with their equipment. The other was the Landing Craft, Infantry (LCI).

The LCVP were also known as a "Higgins Boats" after the name of the company that built them. They were much smaller than the LCI and had a flat bottom so that they could normally pass through the surf and drop their ramps onto the beach. They could then reverse gears and back off the beach to return to the mother ship for more troops, jeeps or supplies. Because they could reach the beach (hopefully) with their payloads, they were used to transport troops of the first wave. The steel plates on the bow ramp gave protection to the troops until the last instant, and then (hopefully), when the ramp was dropped, deposit them onto the beach where they could charge rapidly against enemy positions without being slowed by having to wade ashore.

The LCI was larger and had a deeper draft. Its bow would bottom out in about four or five feet of water. It had the advantage of bringing a larger force ashore (about 200-250 soldiers). It was equipped with a long ramp on each side that extended about twenty feet beyond the bow. When these ramps were dropped, the troops were deposited in waist-deep water where they would be exposed to enemy fire while slowly wading ashore. For that reason, they normally were not used in the first wave. It was very important that a beachhead, however small, be established so that the troops wading ashore from an LCI would have a better chance.

At the Southern France landing, I was part of the second wave, and we came in on LCIs. The landings were made in the daylight. The reason for that was that our Special Services "frogmen" had checked the waters and the beaches and had determined the waters were heavily mined with floating anti-ship mines, and the beaches were heavily mined. The boat operators needed to be able to watch for the floating mines, and the troops would need to see the tripwires for the land mines. Landing in darkness would have greatly increased the risks.

I was the Section Leader of the First Section of the First Platoon of Company H. Therefore I was the first man to debark via the port ramp. As I was approaching the bottom of my ramp, I saw an anti-ship mine bobbing up and down only inches from the ramp. It was about two feet in diameter with detonator spikes protruding in all directions. I thought, "Woe am I if that mine bumps this ramp." I moved faster than I have ever moved before and warned my men to do likewise. Fortunately it did not strike the ramp, and everyone got to the beach safely.

After getting to the beach, I began leading my men, single file, through the land mines. What I saw was large artillery shells planted in the ground with their detonator nose tips protruding from the ground. They were planted in clusters of five shells. They were in about ten-foot squares, with one shell at each corner of the square, and one shell in the center. Every shell in the cluster was connected via trip wires. This included diagonal trip wires to the center shell. If any one of the wires were struck, all five shells would detonate.

I immediately saw the wisdom of the daylight landing. I very carefully located each trip wire and pointed it out to the man behind me, who in turn, pointed it out to the man following him. Each man pointed each wire out to the man behind him. The width of the minefield was about twenty yards and, necessarily, progress was slow. It took my section about five minutes to cross this strip of mines.

Fortunately for us, the fighting in the North following the Normandy invasion had drawn many of the German defenders from the area to oppose our forces there. As a result, the beach defenses were not fully manned. Because of that, our landing in the South was not as difficult as some of the four landings made by the Third Division during the war. Even so, it still was no "walk in the park."

A Sergeant's Revenge

With the troops ashore, the German 19th Army was being driven north from the beaches of the Riviera. It was their intention to make a determined stand at what was called the Belfort Gap, the entrance to the Vosges Mountains. They needed as much time as they could buy to prepare defenses and to get as much of their Army through the pass as possible.

The Germans were very skilled at delaying our advances while utilizing a minimum of personnel and equipment. Ambush with Tanks, Anti Aircraft Halftracks, Self Propelled Artillery and Snipers were their weapons of choice. Just a few of these scattered throughout an area could be very disruptive to our advance.

In the afternoon of September 17, 1944, we were advancing from the town of Lantenot toward the town of Belmont, France. The enemy was not attempting to hold ground stubbornly. He was only using delaying tactics.

Our lead troops were coming out of a stand of trees and entering a clearing. When our lead scout was some distance into the clearing, a shot rang out and the scout went down. A sniper claimed another victim. The scout was not killed. We could see that he was trying to crawl back toward us.

His platoon medic raced out to treat him. The medic was well identified as a non-combatant. He had Red Cross insignia on four sides of his helmet and Red Cross armbands on both arms. Also, all front line medics wore two large pouches filled with medications and dressings, one on each hip. They resembled the pouches you see on the back of motorcycles. It was easy to identify a medic by the large bulges on both sides. Even at night, medics stood out from other soldiers by their silhouette. There is no mistaking one of our medics for a combatant. The sniper picked him off before he could reach the man he was going to help

Then the most amazing thing happened, a second medic dashed out in spite of having just witnessed the sniper's lack of respect for the Red Cross symbol. He was also shot.

Our advance was halted and a search for the sniper began. After about ten minutes his hiding place was discovered. Our troops kept firing on his position to keep him pinned down while two of our men moved in close and took him prisoner. He was a sergeant.

The prisoner was brought in to the edge of the clearing. As the German stood with his hands in the air, the sergeant of the men he had shot, walked up to him and, with his rifle, delivered a horizontal butt stroke that removed his ear and a portion of his face.

The prisoner was then escorted, bleeding profusely, to the rear.

About an hour later I was wounded. (See "Saved by a Chapel".) I was taken to what was called an evacuation hospital to have shrapnel removed from my leg.

About nine PM I was taken into a tent and placed on an operating table. On the operating table to my left was the German sniper. He was being fed blood plasma from a bag hanging above the table.

When the doctor that was going to work on me came in, I asked him how the German sergeant to my left was doing. He said that it was a fifty-fifty chance that they could save him.

I then told the doctor what had happened and how the German got his wound. The doctor put his finger on the side of my head and said, "When you see the sergeant again, tell him to aim about here. He will save us from having to use our precious blood plasma the next time".

I did not approve of our sergeant's action. I did understand his motivation. Perhaps justice was done. I just know that I would not have abused a prisoner.

Stop it Yourself

We invaded Southern France August 15, 1944. The German 19th Army that opposed us began a withdrawal up the Rhone Valley. They wanted to pull back to the Vosges Mountains where they would have a tremendous advantage in setting up a defensive front and would have much shorter supply lines.

The enemy was making a controlled withdrawal, something the Germans were very skilled at. They always left combat units behind to delay us, while the main body withdrew as rapidly as possible. We never knew where these delaying units would be. This required our constant probing with combat patrols to locate them before our main body was caught in their defensive traps. One night my machinegun section was assigned to a rifle platoon on one of these combat-reconnaissance patrols.

Now, I mean no disrespect toward the officer in command, but many of our officers had no more military background or training than the enlisted men. Since there was only one officer commanding a platoon of thirty to forty men, and since he was always at or near the front of his men, the casualty rate was quite high among platoon leaders and they were constantly being replaced by officers straight from the States. Until these officers acquired a week or two of on-the-job training, we had to be very careful in following their orders.

Our patrol had been moving westerly along a two-lane paved road. When we came to a "T" intersection with another road of the same design, our column turned right onto the other road in a northerly direction. After traveling a short distance along this road, the column stopped. My machinegun section followed immediately behind the rifle platoon. This put us at the rear of the column and still very near the intersection.

I never knew why we had stopped. I guessed that the lieutenant at the head of the column was under a blanket referring to a map. After a wait of a few minutes I heard "sqwueeck-sqwuack, clank clank" about a hundred yards behind us. The sounds continued and it was obvious the sounds were getting closer. I had recognized the sound instantly. It was a German tank changing its position and was moving very slowly in an effort to keep its noise level as low as possible.

On night patrols we communicated by whispering to the man next to us and having him pass it along via the man next to him. I sent the following message forward to the lieutenant: "Tank approaching from the rear." This message was passed forward. The lieutenant passed back the following message: "Stop it. If it is one of ours, send it forward."

Well, there were two important elements missing from the lieutenant's order: One, how were we to stop the tank with nothing heavier than a 30 caliber machinegun? Two, what we should do if it was not one of ours.

By this time, the tank was getting uncomfortably close, so I passed back the following message, "Stop it yourself. I'm getting my men off the road." Soon after moving my men a comfortable distance from the road, the lieutenant decided that my advice had merit and he and his men joined us.

As we lay quietly off the road for a minute or two, the sounds changed into sounds that told me the tank was making a slow turning movement on a paved surface. The tank was turning right and proceeding up the road we had come from. The tank had been parked a hundred or so feet south of the intersection. We had passed right under its nose, so to speak, when we passed through the intersection. The benefits of silence on night patrols was clearly demonstrated by this experience.

We waited about ten minutes until we felt it was safe and then moved on.

Saved by a Chapel

Late in the day on September 17, 1944, near Belmont, France, I had another close call. Thanks to a beautiful black and gray granite chapel, I was able to escape from a very tight situation.

This day began early. At 3:40am 1st Battalion, 30th Regiment, was committed to an attack on the town of Lantenot. Company F, 2nd Battalion, attacked to the southeast from Rignovelle to assist in the 1st Battalion's attack on Lantenot. My machinegun section was assigned to Company F.

The enemy stayed very active throughout the day. He was making a controlled withdrawal and was never out of contact for more than a few minutes at a time. His intention was to make a determined stand a few miles to the north at what was known as the Belfort Gap, entrance to the Vosges Mountains. He was buying as much time as possible with these tactics.

Companies E and G, 2nd Battalion, attacked toward Belmont. Belmont is about three miles north of Lantenot. Belmont fell to Companies E and G shortly after 2pm and Company F entered the northern part of Lantenot a few minutes later.

After clearing Lantenot, Company F was committed to an attack to the north to clear the road between Lantenot and Belmont. We met sporadic resistance as we made our move toward Belmont. By about 6pm, we had reached a point very near Belmont and were told to hold position and wait for orders.

The position selected for one of my guns was very exposed. The other was placed in a more protected location. I decided to help my men dig the hole for the more exposed position.

This gun was being placed about three feet from the end of a thick hedge approximately four feet high. The hedge was to the left of the gun, and about another eight feet to the left was a very large log. The log was parallel to the hedge and partially under it. I had left my rifle leaning against the log. It was my thought that, if we had to return fire from this location, I could use the log for small arms protection while firing through the hedge with my rifle as I also directed the machinegun's fire.

About twenty yards behind the gun was a granite building about 20'x30'. I guessed it to be a chapel of some sort, or possibly a Mausoleum. To our front was an open field that was cleared all the way to a heavily tree-lined road about three hundred yards from our gun position.

I was taking a turn at digging when I heard a voice behind me. I looked around and saw a First Lieutenant with his radioman. They were artillery observers and were giving coordinates to their guns for possible future use. They were sitting on the ground in full view of any enemy that might be around as though they were on a Sunday picnic. I cautioned the Lieutenant that it was very risky for him and his radio to be so exposed. His reply was, "It's alright Sergeant. G-2 reported this area cleared of enemy activity." In response, I informed him that we had been in contact with the enemy only twenty minutes earlier, and that I thought it very likely that we could be fired upon.

As I turned back to my digging, I thought, "What a beautiful target we make, a machinegun and an artillery observer with radio." All are very high priority targets. The enemy could not pass up an opportunity to get all with one long burst of fire. Before I could take another shovel of dirt it happened. The enemy opened up with a long burst from twin 31 caliber machineguns followed by four or five 40mm anti aircraft shell bursts. The first shell exploded a few feet in front of me and about three feet above ground. A piece of shrapnel from that shell caught me in the inner part of my left thigh.

I dropped into the hole and looked back over my shoulder to see if anyone else had been hit. I saw a First Lieutenant and a radioman heading for the crest of the hill. The Lieutenant was leading by a good three strides and pulling away. Pfc. Goble, my number one gunner, whose hole I was digging, was only a few feet behind. Further to my right I saw a number of GI's breaking for the crest of the hill. They were all doing what is prudent when caught in the open without foxholes for protection. I told myself, "You are the only toy left for them. You are going to get a lot of attention."

I knew from the machinegun fire followed by aerial bursts that I was up against one of their anti aircraft halftracks. It is armed with a 40mm cannon and two 31caliber machineguns. The machineguns are mounted coaxially with the cannon so that they all fire on the same line. Even though designed for anti aircraft use, it was very effective against troops and lightly armored vehicles. This was their favorite weapon for delaying actions. It was mobile and had a lot of firepower. It had to be located on the tree-lined road below me. I thought that if I could spot its location, I would try answering with my machinegun.

I raised my head to take a look. My helmet was barely above ground when I received another long burst from their machineguns followed by four or five 40mm bursts. I saw leaves flying from the hedge as the bullets sprayed through it. I tried a second peek with the same response.

It was obvious that the officer in command had his field glasses on me, and his gunner had his finger on the trigger. I now knew that I would never be able to spot them nor return their fire. I also knew that I could not last long in such a shallow hole with 40mm shells bursting a few feet above ground.

I had been hit in the left thigh and did not know the severity of the wound. I knew it was not a bad wound unless it had broken the bone. I did not think that it had. I knew that, regardless of the severity of my wound, I had no choice but to make a run for it.

I formulated my plan. I decided that I would pull my right leg up like a frog before leaping. I would raise my head one more time to provoke another burst of fire. Then, when the last shell exploded, I would push off with my right leg and duck low behind the hedge. I would grab my rifle as I passed the log and, staying as low as possible, dash for the protection of the chapel.

I raised my head as planned and got the expected response. As the last shell exploded, I pushed off. They had not expected such a move and were unprepared for it. Fortunately my wound was not serious and I had full use of both legs. By the time they could react, I already had my rifle and was headed for the chapel. This required them to adjust their aim a bit, and by the time they fired again, I was rounding the corner of the building. I saw pieces of granite flying off the building as I dove behind it.

There was a side door that I entered. Inside were a number of other GI's who had taken refuge. Had that chapel not been where it was, there is good chance that I would not be writing about it now.

Romberger's Close Call

Pfc Roland R. Romberger

On March 19, 2007, I received an email from Roland R. Romberger telling me of his close encounter that occurred simultaneous with my close encounter with the enemy on September 17, 1944 near a granite chapel near Belmont, France. (See my memoir, “Saved by a Chapel” above.)

Roland was number one gunner for one of the machineguns under my command. As stated in my memoir, I was assisting with digging a position for one of the machineguns while Roland and his assistant gunner were digging for the other gun about fifty yards from where I was.

With Roland's permission, I am reproducing his email below just as I received it:

I just finished reading your memoirs for the fifth time, and being with you a good bit of the time, it sure brings back memories during our good and bad times. Who can forget the chapel we used for protection after you were wounded. I don't remember that I ever told you what happened to me during those minutes when they opened fire.

When the shells were exploding above us we had not dug our gun in, nor did we have time to dig a fox hole, so we ran for the back of the church, but before I made it to the rear of the chapel machine gun bullets were hitting the ground near me and I dove on top of some riflemen who had dug a fox hole about 3 ft deep next to me. Since I was the third one on top in the hole I felt I must be crushing the one on the bottom. So, in a matter of seconds, I got out and ran to the back of the chapel for protection from the shrapnel and machineguns.

My brother-in-law had just sent me a smoke pipe which I carried in my shirt pocket. Somehow it fell out of my pocket when I dove on top of those men in the hole. So, after the firing stopped, I went back to see if I could find it. The men in the hole were both dead from the shells that exploded above them. My pipe was in the bottom of the hole, lying in their blood. I never picked it up, but felt sick about the men in the foxhole.

Had I stayed another half minute, my life would have ended as I would have been the first to get it. I guess I can never understand the way things happen during war time.

Wishing you happiness and God's daily blessing,

— Roland

Another close one for Roland

In frontline combat there are many close calls, but some are a bit out of the ordinary and stay with you forever. Another such event occurred about a month following the event recorded above.

I had another close call in the Vosges Mountains fighting. It happened late one night in mid-October, 1944. I was in a crouching position when three enemy soldiers suddenly appeared above me. The leader was carrying a submachine gun. The other two were carrying two large anti-tank land mines each. They were obviously on a mission to mine a roadway and had lost their bearings.

I saw the leader making a move to bring his weapon to bear on me. (My parents were German immigrants and my entire family spoke German fluently. This was very instrumental in my survival.

Seeing the enemy's intention, I shouted in perfect German for the soldier not to shoot. This apparently caused the soldier to think I was a friend. At any rate, he hesitated just long enough for me to grab the muzzle of the machinegun and move it to one side. At this same moment, the soldier fired the weapon, putting a burst of bullets through my hand.

I ran a few steps and dove for cover and at the same time shouted for our man, who was manning one of our guns nearby, to fire. Our man opened fire without knowing what or where his target was. Of course, his fire was not a threat to the enemy, but in the dark they had no way of knowing that, so the three of them took off running at top speed, leaving four anti-tank mines behind.

I was returned to my unit after my hand was healed several weeks later.

— Roland Romberger

Oops!

In late September, 1944, I was in a hospital ward recovering from surgery to remove a shell fragment from my leg.

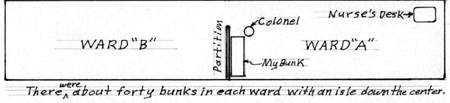

I was assigned to the bunk that was next to a partition that divided Ward "A" from Ward "B".

A partition divided Ward "A" from Ward "B"

About three times a week, the staff would distribute a can of beer to all those who wanted it. Of course we had no way to cool the beer, so we just drank it warm.

To open the beer cans we used a small can opener that came with our rations. The can opener had a beak-shaped blade that punctured the lid next to the rim by way of a forward rotation of the handle that it was attached to. Each forward rotation would make a cut about one quarter inch in length. After each rotation, the cutting blade had to be moved slightly to lengthen the cut with another forward rotation. By repetition, the cutter would finally make a full trip around the lid so that it could be removed.

However, for beer drinking, we only made a few cuts for an opening to drink through, and on the opposite side of the can we made a single cut for an air breather hole.

One afternoon my friend, Errol Johnson, in the adjacent bunk, offered me one of his cans of beer which I accepted. When I made the first cut with my can opener, a stream of beer shot out that would have gone at least twenty feet if it had not hit a colonel full in the face. The colonel was coming from Ward "B" and entering Ward "A" around the partition between the two wards. His timing was very unfortunate for all involved.

The following events happened so quickly that I cannot put a time line on them. They were so closely spaced that they were almost simultaneous. I had been sitting on the edge of my bunk when I opened the can. When the beer shot into the air, I dropped the can opener and placed my right hand over the can to stop the fountain of beer. Next, I was suddenly aware of the colonel's presence and the consequences of my actions. So I jumped to my feet and, in a panic, gave the colonel a salute with beer dripping from my right hand. I held that salute waiting for the colonel to return it, while beer still over-flowed from the can in my left hand.

The colonel did not return the salute, but stood there staring me down while beer dripped from his chin, and, after what seemed an eternity, turned and headed for the nurse's desk. I dropped my salute and decided not to report the colonel for failing to return it.

When I turned to my friend, he was trying to stuff a pillow into his mouth to stop the laughter. I then knew what had happened, and what he finally admitted to. He had vigorously shaken the can of beer before offering it to me.

By the time the colonel reached the nurse's desk he had his handkerchief out and was drying his face. He called the poor nurse to attention and dressed her down one side and up the other for all to hear. He told her that there was never to be another can of beer opened inside the ward. If the patient was confined to his bunk and could not take his beer outside, it would be her responsibility to take it outside and open the can for the patient.

I felt very badly for the nurse, but it was my friend, Errol Johnson's fault. He mischievously had put the chain of events into motion.

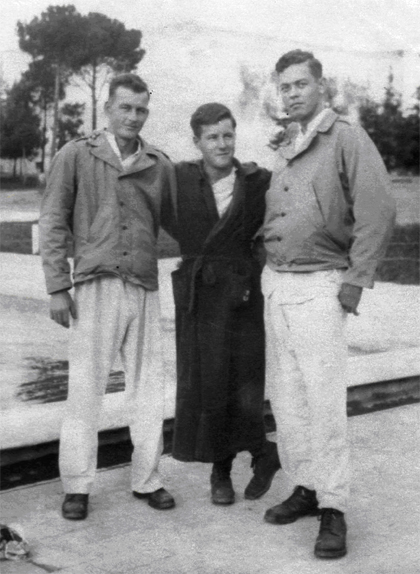

This picture was taken outside our ward in an Army hospital in Italy, September 1944. Billy Canfield is on my right and Cecil McDonald on my left. We were classmates in Bay County High School, Panama City, Florida. We went into the service about the same time. The next time we met was in this hospital ward. Billy was in the paratroopers and Cecil was in the 34th Infantry Division, my brother, Frank's division. We frequently ran across our friends over there. Seemed like everyonw was in the service.

Albert S. Brown | Infantrymen | Dull Day |

Foreword | Do Something, ...

Anzio | Southern France |

Colmar | Germany | Epilogue

Reprinted by permission. |