Staff Sergeant

Albert S. Brown

Infantrymen

Dull Day

Foreword

Do Something,

Even if it's Wrong

Anzio

Southern France

Colmar Pocket

Germany

Epilogue

Contact Al

dogfacebrownie@gmail.com

![]()

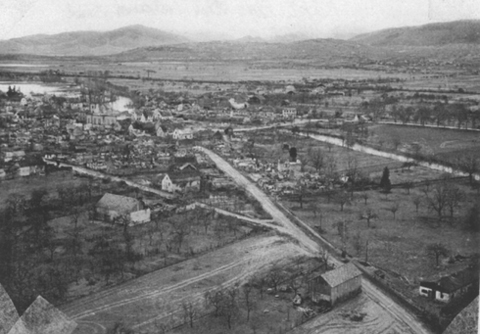

Colmar Pocket

Aerial photo of one of the villages in the Colmar Pocket and its surrounding terrain. (photo by Jack Cole)

Colmar Pocket, the Other Bulge

Almost everyone has heard of "The Battle of the Bulge". Few people have heard of "The Colmar Pocket". Both were very related in the German's scheme.

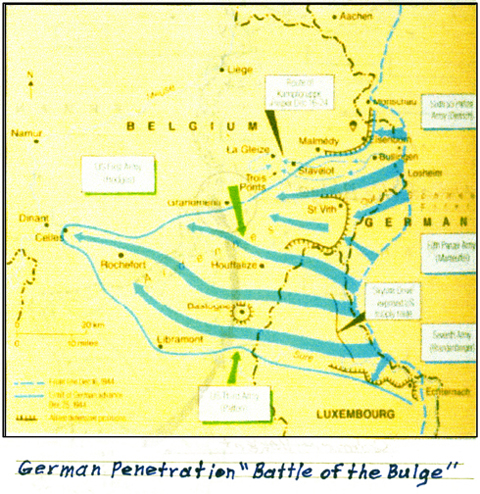

The "Bulge" was caused when the Germans mounted an all-out drive that broke through the Allied lines and gained a very dangerous amount of territory.

The Colmar Pocket was the result of the French First Army's inability to drive the Germans back across the Rhine River. The Seventh Army, the army my division was a part of, was to the left of the French. The French were the most southerly located army. Their zone of responsibility extended to the border of Switzerland.

Patton's Third Army was to the Seventh Army's left (north). By the end of November 1944, the Seventh Army and the Third Army had driven the enemy back across the Rhine and behind its own borders. The only enemy units west of the Rhine River in the southern region were in the vicinity of Colmar, France, in the French sector. This bulge, or pocket, extended 35 to 40 miles west of the Rhine. This pocket posed a serious threat to the rear of the Allied Armies to the north; i.e., Seventh and Third. It had to be eliminated.

Several units from the Seventh Army were sent to join the French First Army. The Third Infantry Division was one of those units to go under French Command. The American divisions were to make the assault to clear the Colmar Pocket. The Third Division was the lead division in clearing this threat to the armies to the north.

At the time, the Seventh Army was just standing guard along the Rhine River. French forces took over Seventh Army positions so that the American units could be sent into the Colmar fighting.

Eliminating the Colmar Pocket began December 15, 1944, and by February 19, 1945, no more German units were west of the Rhine in the southern region.

In the beginning of this operation, the enemy was attacking aggressively in an attempt to break out and drive to the north. However, every attack was stopped cold.

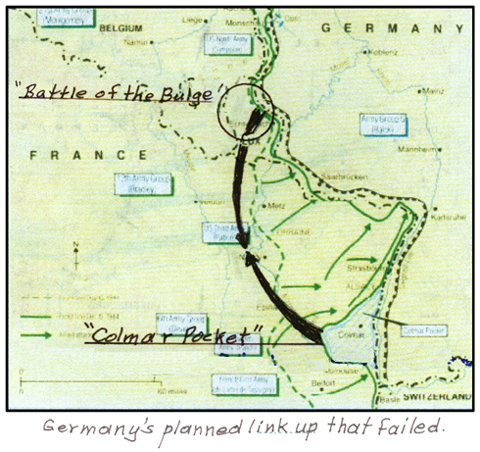

The attacks in the Colmar area were coordinated with the attacks to the north that are so well known as "The Battle of the Bulge". The German divisions from the bulge were to drive south to link up with their divisions driving north from Colmar. The object was to cut off the Third and Seventh armies along the Rhine. (See map.)

If the enemy had succeeded in breaking out of the Colmar Pocket, the situation could have gotten very serious indeed. Supply lines to the US Third and Seventh armies would have been cut. Patton's Third Army would have had to eliminate the threat from its rear and would not have been able to drive to the north to rescue US troops in the bulge as it did.

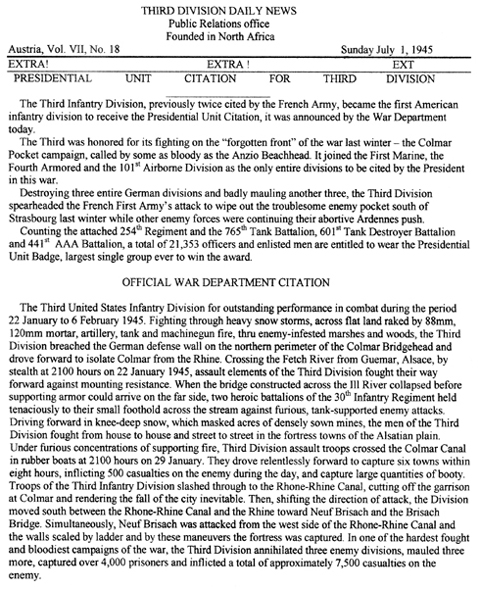

Holding the enemy inside the Colmar pocket was just as critical as driving him back from the Bulge. The Third Infantry Division was at the forefront of all the Colmar fighting and was primarily responsible for stopping the enemy from breaking out as he had planned. The Third Division also took the lead in driving the enemy back and ultimately eliminating the Colmar Pocket. For these actions, the Third Division was awarded a Presidential Unit Citation.

The Night Before Christmas - 1944

December 24, 1944, my machineguns were in the basement of a farm house on the outskirts of Sigolsheim, France. The guns were positioned to fire through ground-level basement windows.

It was brutally cold and a time to be indoors whenever possible. The temperature outside was below zero with more than a foot of snow. We were told that temperatures were at a fifty-year low in that area. Our machineguns, being water cooled, required the use of anti-freeze to keep the water from freezing. We were out of anti-freeze, so we had filled our guns with schnapps from a barrel in the basement to tide us over until new supplies arrived.

Above us, on the second floor, leaning against the sill of an open window, was a German soldier, frozen stiff. He was still holding his rifle pointing in the direction from which we had attacked earlier that day. He was older than the average frontline soldier. I guessed him to be 45 to 50 years old. He was wearing military issue wire-frame glasses with circular lenses. On his finger was a wedding band. He was obviously a husband and, in all probability, a father. He would never share another Christmas with his family. How sad.

For the most part, frontline positions were quiet. There was an occasional short machinegun burst from one side or the other and random, harassing, artillery shells could be heard intermittently, but none of this was in our immediate area. Then, suddenly, about 10 PM, there was an intense in-coming artillery barrage in front of our position. It lasted only a minute or two, and then it was over. A reconnaissance patrol from one of our rifle companies had been detected as it was returning from its mission and the enemy was really giving it to them.

A couple minutes later, the patrol entered our basement carrying a badly wounded soldier and left him with us. There was nothing anyone could do for him. His brains were protruding through a shrapnel hole in the center of his forehead. I guessed the hole to be an inch and a half square. There was no exit hole. The shrapnel was still inside his skull.

I reported the wounded man to our command post and asked for a medical evacuation team. The litter bearers did not arrive until just before dawn, Christmas Day. In the meantime, the man just lay there motionless, except for light breathing. I found it difficult to believe that he was able to live with such a horrible wound. Mercifully he was not conscience.

So this was my Christmas Eve 1944, a dead enemy above me and a dying fellow soldier at my feet. While my men slept around me, I had no desire to sleep. I just sat in a chair, wondering if there was something I could and should do for this man. But nothing came to mind. It must have been about 2 AM when I could no longer see signs of breathing. He had made it to his last Christmas. One thing for certain, I knew that I would never have another Christmas Eve without this night coming back to me. I was so right.

The Other Murphy

Almost everyone in the US has heard of Audie L. Murphy, famous war hero who earned every medal for valor that our country has to offer. Audie was in Company B, Fifteenth Infantry Regiment, Third Infantry Division.

It was near Holtzwihr, France, on January 26, 1945, that Audie earned the Congressional Medal of Honor, our Country's highest honor.

Three days prior to that, on January 23rd, and within two miles of the place where Audie earned the CMH, another Murphy willingly gave his life in order that about twenty of his comrades could live. For his sacrifice, Sgt. Jack H. Murphy, Company H, Thirtieth Infantry Regiment, Third Infantry Division, was awarded, Posthumously, The Distinguished Service Cross, our Country's second highest award for bravery.

The following is Sgt. Jack Murphy's story

Sgt. Murphy was Squad Leader of one of the two squads in my section. He was in command of one thirty-caliber machinegun and seven men.

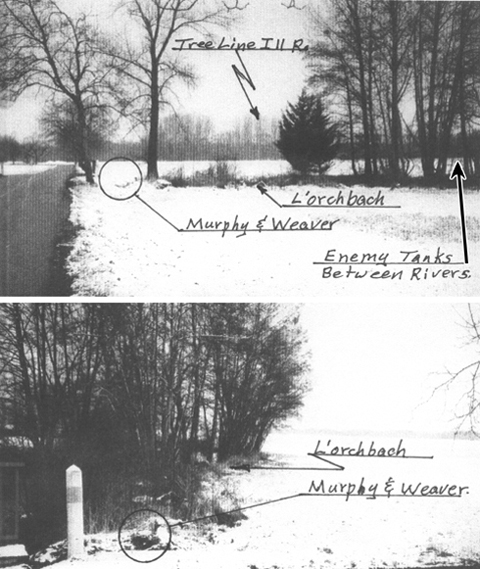

Late in the day on January 23, 1945, the 30th Regiment was advancing without tank support toward Riedwihr and Holtzwihr, France. We had no tanks because the bridge across the Ill River had collapsed when our first tank attempted to cross. We crossed on a footbridge that our engineers had built. Our lead elements were about a mile beyond the Ill River at this time.

The 1st and 3rd Battalions, 30th Regiment, were leading the attack. The 2nd Battalion (our battalion) was in reserve and following close behind the 1st and 3rd.

Knowing about the bridge collapse, the enemy sent several tanks against the infantry. He need not fear opposition from our tanks. This forced portions of the 1st and 3rd Battalions to fall back rapidly. The 2nd Battalion was ordered to set up defenses along the banks of a smaller river named "L'orchbach" on our maps. The Orchbach was about 200 yards beyond the Ill River where the bridge had collapsed. The Orchbach Bridge was not damaged and was very capable of supporting tanks.

My people and I had just crossed the Orchbach when the word was sent back to defend there. Sgt. Murphy and his squad set up positions at the bridge. I took the Second Squad and set up position about 80 yards to the north. There was no time to dig in. I chose a large bomb crater for the second gun's position. The bomb crater was about eight feet in diameter and was only a few feet from the bank of L'orchbach.

Our guns would be useless against the tanks. But, if their infantry accompanied the tanks, our guns could be of some use.

We had barely set up our machineguns when our troops came into view. They were coming out of a stand of trees about 400 yards to our front. The enemy tanks were in close pursuit. Knowing that our thirty caliber weapons were useless against the on coming tanks, Sgt. Murphy ordered his men to withdraw while he took over the machinegun. Murphy's number one gunner, Pvt. Clifton Weaver, refused to leave and stayed on to help operate the gun.

As our troops were attempting to escape the withering fire from the German tanks, a group of about twenty men took refuge in the roadside ditch about fifty yards in front of Murphy's position. As one of the tanks approached this group of men, it kept them pinned down with its machinegun. It was obvious that the intention was to hold the men there until the tank was close enough to depress its cannon and eliminate them at point blank range.

Realizing the plight of these men, Sgt. Murphy opened fire on the tank to take its attention from the men in the ditch. The tank switched its fire to Murphy and Weaver. The dual that followed was short lived. After a few exchanges with its machinegun, the tank ended it with one round from its cannon. However, while Murphy was dueling the tank, the trapped men were able to escape.

Murphy and Weaver knew that they could not survive such an exchange with a tank. They willing gave their lives that others could survive. Pvt. Clifton Weaver was awarded the Silver Star Medal, Posthumously, for his part in that engagement.

In all, I lost five of my men at the bridge. Three of Murphy's men attempted to swim the river rather than be exposed by crossing over the bridge. These men drowned in the ice filled river. I did not mention it before, but the temperature was around minus 15 Deg. F, and the ground was covered with about two feet of snow.

A Dash in the Snow

Third Division soldiers wearing snowsuits

in the Colmar Pocket — January 1945

Late in the day on January 23, 1945, the 30th Regiment was advancing without tank support toward Riedwihr and Holtzwihr, France. We had no tanks because the bridge across the Ill River had collapsed when our first tank attempted to cross. We crossed on a footbridge that our engineers had built. Our lead elements were about a mile beyond the Ill River at this time.

The 1st and 3rd Battalions, 30th Regiment, were leading the attack. The 2nd Battalion (our battalion) was in reserve and following close behind the 1st and 3rd.

Knowing about the bridge collapse, the enemy sent several tanks against the infantry. He need not fear opposition from our tanks. This forced portions of the 1st and 3rd Battalions to fall back rapidly. The 2nd Battalion was ordered to set up defenses along the banks of a smaller river named "L'orchbach" on our maps. The Orchbach was about 200 yards beyond the Ill River where the bridge had collapsed. The Orchbach Bridge was not damaged and was very capable of supporting tanks.

My people and I had just crossed the Orchbach when the word was sent back to defend there. Sgt. Murphy and his squad set up positions at the bridge. I took the Second Squad and set up position about 80 yards to the north. There was no time to dig in. I chose a large bomb crater for the second gun's position. The bomb crater was about eight feet in diameter and was only a few feet from the bank of L'orchbach.

(The above four paragraphs are copied from my WWII Experience entitled "The Other Murphy." The following events occurred simultaneous with and immediately after Murphy and Weaver's heroics.)

The crater was not large enough for the entire squad. The men would be without protection on top of the snow, and with a river full of ice to their backs. Their rifle fire would be useless against the tanks. I had them leave their ammunition for the machinegun and instructed them to follow the stream to Illhausern, a small town to the north that was under Allied control. Two of the men and I stayed with the gun. Our machinegun would also be useless against the tanks. But, if enemy infantry accompanied their tanks, our gun could be of some use.

Between the bomb crater and Murphy's position was a 57mm anti tank gun with a two-man crew. They were partially hidden in a clump of small trees growing along the bank of the river. This gun belonged to one of the two lead battalions and had been placed in position prior to the collapse of the Ill River Bridge.

We had barely gotten our guns set up when our troops began falling back from a stand of trees 400 yards to our front. Soon I saw three enemy tanks pursuing them. The tanks were about 200 yards behind and firing their machineguns. Our boys were taking casualties.

The 57mm gun to my right fired on one of the tanks. The shot was not effective. And, about ten seconds later, our 57mm was history. The tank had returned the fire and knocked the gun out with one shot.

Shortly after this, I heard our machine gun at the bridge firing. Their position was not visible to me because of the small trees growing along the bank of the stream. I saw the lead tank firing its machinegun in that direction. It was obvious that Murphy and his men had just bought into some big trouble. After a few exchanges with its machinegun, the tank fired its cannon. I heard the shell impact near the bridge. After that, there was no more firing from the bridge site.

Some of the men who had been flushed from the trees, fled to the north toward Illhausern. Others fled along the road past Murphy's position and crossed the Ill River using the footbridge. Some hid in small depressions in the snow in the field in front of our position. All of our troops were wearing white snowsuits that made it difficult to be seen in the snow if they did not move.

Two of the tanks crossed the Orchbach in pursuit of the men headed for the footbridge. This put them between the Ill and Orchbach Rivers, and behind our position in the bomb crater. My men and I laid low in the crater. We would have no chance if spotted.

It was dusk when all of this activity began. Within a half hour it was quite dark. It was my intention to withdraw to Illhausern. But first I had to check on my men at the bridge. Now that it was dark I would have a chance to check on them without being seen. I slipped out of the bomb crater and, staying below the riverbank as much as possible, made my way to the bridge. As I passed the 57mm anti tank gun, I saw that both crewmembers had been killed and the gun was lying on one side.

When I reached the bridge position, I saw that both Murphy and Weaver were dead and their machinegun was destroyed. I did not see any of the other members of the First Squad. I learned later from two of the men that Murphy had ordered them to withdraw. They had withdrawn to Guemer. They told me that three of the men attempted to swim the river rather than risk exposure on the bridge. They were never seen again.

I returned to the bomb crater to join the two men that I had kept with me. Just as I reached the bomb crater, a tank left the road and pulled to a stop about fifty yards in front of us. Two men from the 1st Battalion were flushed out by the movement of this tank and joined us in the crater. I told the men that we would withdraw as soon as the tank moved away. In the meantime we had to remain motionless.

The Third Division frequently used what it called artificial moonlight to light up the battlefield at night. They would shine a number of huge searchlights into low hanging clouds and the reflection would make it possible to see objects for short distances. The lights were on and I was wishing that they would turn them off.

As we waited, I saw something moving on top of the snow a short distance to our left front. It turned out to be one of the 1st Battalion men crawling toward the tank. I could just make out that he was dragging something about four feet long. I then realized that he had a bazooka and intended to fire on the tank. In basic training we were taught that the bazooka would knock out a tank. We soon learned that it would not, but it was difficult to convince new arrivals from the States.

I knew what the outcome would be if he fired on the tank. When the soldier was about thirty feet from the tank, he stood up and shouldered the weapon. Without rising, I shouted at the man not to fire. It did no good. He fired into the right side of the tank. We watched from our crater as the tank swung its turret toward our man and cut him down with its turret-mounted machinegun. It was what we called "bazooka suicide."

Apparently this activity caught the attention of one of the tanks that had crossed the Orchbach and gotten behind us. It pulled up very close to the riverbank, directly opposite our hiding place. The river was only about twenty feet wide at this point. The tank was barely ten yards from us. We could see the tank commander's head above the turret as he gave orders and looked for targets.

The riflemen who had joined us began to get edgy. I was afraid they would bolt. I grabbed them, one with each hand, and whispered to them not to move or breathe.

The tank that was in front of us moved toward the road shortly after the other tank pulled up to the river. We had traded one tank fifty yards away for one ten yards away. I was not in favor of the exchange. However, I was determined to wait it out. I felt certain that, if we did not move, our white suits would save us from detection. After what seemed to be forever, but what was probably less than five minutes, the tank commander gave an order, and almost immediately the driver revved the engine. I was pleased at this. It told me that they were going to move. But the riflemen were spooked by it; and leaped from the hole to run.

I heard the tank commander shout, "Auchtung Amerikaner." I ordered everyone to run for it. We stayed close to the riverbank that ran nearly ninety degrees to the left of the tank's front. In order to track us, the machinegun's aim had to be constantly changing to the left. The gunner would not be able to see his sights at night and had to rely largely on guesswork. If we had run straight away from him, his work would have been greatly simplified.

In spite of his aiming difficulties, the gunner was able to track us very well. Bullets were flying all around us. They were only missing by inches. One of the rifleman was running about ten feet in front of me. A swarm of bullets barely missed me but apparently caught the rifleman in the head. His helmet flew off and he hit the snow in front of me. He landed like a dropped brick. One bullet spun my helmet 90 degrees on my head. I later discovered that the bullet had removed the metal connector that secured the right half of the chinstrap to the helmet.

After a dash of about eighty yards, we came to a bend in the river that put it in our path. We went feet first into the ice filled water. We grabbed bushes above the water line and pulled ourselves up out of the water but stayed below the top of the bank.

The tank continued to sweep the area above us with machinegun fire for another minute or two. My next concern was whether the other tank that was on our side of the river would come for us. I decided not to wait for the answer. We got out of the river and headed for Illhausern. Of the five who began the dash from the bomb crater, four made it to safety.

When we reached Illhausern, we were directed to an assembly area that had been established to reunite units that had been scattered. Outdoor gasoline heaters had been fired up to warm and dry us out. Our cooks served us hot C-rations that warmed our insides.

Ordinance issued us new machineguns and ammunition to replace the ones left at the Orchbach.

By morning, our battalion was completely reorganized, and moved out to reclaim the ground that had been lost. This time we had our tanks with us. The engineers had completed a bridge during the night.

Rude Awakening

It was about January 27 or 28, 1945, during the fighting for the town of Holtzwhir, France, when I had the following experience:

The Germans had constructed numerous concrete bunkers in this area. Some were not designed for firing weapons from. They were more suited for storing material. As we approached one of those bunkers, I decided to make sure the bunker was clear of enemy soldiers. The bunker was a hundred or more feet long and about ten or twelve feet wide.

It had entrances at each end. About five feet inside each entrance was a concrete wall in front of the opening that went more than half way across the width of the bunker. This wall was designed to stop projectiles or shrapnel from entering the bunker. Not wanting to expose myself to possible enemy fire, and staying behind this wall, I reached around the wall and fired my rifle into the bunker. Almost immediately, there was a banging and clanging of what sounded like someone stampeding through a lot of pots and pans.

I waited a few seconds before looking around the wall. When I did, I saw two German soldiers in the far entrance-way. They were obviously extremely frightened and uncertain as to what to do. I had apparently awakened them from a sound sleep. I ordered them to go outside.

As they exited their end, I moved outside and covered them with my rifle and ordered them to come to me, which they did.

When I disarmed them, one of the weapons was a knife of very high quality steel. It is hollow ground and will hold a very sharp edge. This knife is now in my wife’s kitchen and is one of her favorite knives.

Clark's Helmet

January 28, 1945, my Battalion had cleared the enemy from north of the Colmar Canal near Colmar, France. We had reached the north bank of the canal shortly after dark. We were ordered to dig in pending further orders.

Corporal Thomas L. Clark, Jr. was our platoon liaison at the time. Clark and I were going to share a foxhole this night. I wanted him with me in case I needed to communicate with the rifle company that we were then supporting.

After about two hours of digging, we had a hole that we felt was adequate, except that the fresh earth that we had thrown up from our excavation stood out in dark contrast to the two feet of snow that was on the ground. It was our intention to rest a few minutes before pulling surrounding snow over the freshly excavated earth. After all, we thought that as long as we hid our excavation before daylight it would be OK.

We were resting with our heads above ground trying to get acquainted with our surroundings. We were especially interested in what might be on the other bank of the canal. Suddenly, there were white flashes of a machinegun from the opposite bank of the canal. Simultaneous with the flashes, dozens of bullets were cracking within inches of our ears. Miraculously, we were not hit.

Obviously, our excavation was visible against the white snow. The canal was only about thirty feet wide, so the distance was very short. Also, our heads were easily seen at that distance.

Let me slip in a little "side bar" here. The enemy machinegun fired 1,500 rounds per minute. That calculates to twenty-five rounds per second. It only needed a very short burst of fire to spray a target like a shotgun.

After a minute or two with our heads down, Clark announced that he was going to get that SOB. I told him that he would do no such thing. I pointed out that our antagonist was obviously part of a patrol that had just moved in. It was not a permanent position or they would have fired on us during the two hours that we were digging. I also knew that they would not charge our position with the canal between us. All we had to do was stay down and wait for the patrol to move on.

Clark seemed satisfied for a while, but he was not known for his patience. He wanted to take a shot at them. I tried to explain that if they were still there, the gunner would have his gun trained on our position with his finger on the trigger. Clark would never get a shot off if he tried. If they had moved on, Clark would have nothing to shoot at. So what was his point of taking the risk? I suggested that we wait an hour. Then it should be safe and we could finish our foxhole by hiding the fresh dirt under some snow.

Clark refused to listen, he raised his head above ground and instantly there was a burst of machinegun fire. Clark's helmet landed in my lap. Clark's body fell back against me. My thought was that he would be dead. If he wasn't dead, I would not be able to evacuate him. Also, how could I treat head wounds in a dark foxhole?

With these thoughts racing through my mind, I ran my hands over his head and felt blood. Clark said, "Damn". Good. At least he was alive.

I examined him as best I could and determined that he had three wounds, but they were only scalp wounds. I wrapped his head with gauze from his first aid kit. All soldiers are issued first aid kits and are required to carry them at all times.

Clark never lost consciousness. The bandages soaked up most of the blood and bleeding stopped in a short time.

After a good two-hour wait, he helped me pull snow over our position and then walked himself back for medical attention.

I examined his helmet. The helmet had eight holes in it where four bullets had entered and exited. The fiberglass helmet liner, on which the steel helmet sits, had four long gashes in it. Every support strap (six) that contact the wearers head had been cut in two.

Clark told me later that he had sent the helmet and liner home for a souvenir.

Albert S. Brown |

Infantrymen |

Dull Day |

Foreword |

Do Something, ...

Anzio |

Southern France |

Colmar |

Germany |

Epilogue

Reprinted by permission. |