Staff Sergeant

Albert S. Brown

Infantrymen

Dull Day

Foreword

Do Something,

Even if it's Wrong

Anzio

Southern France

Colmar Pocket

Germany

Epilogue

Contact Al

dogfacebrownie@gmail.com

![]()

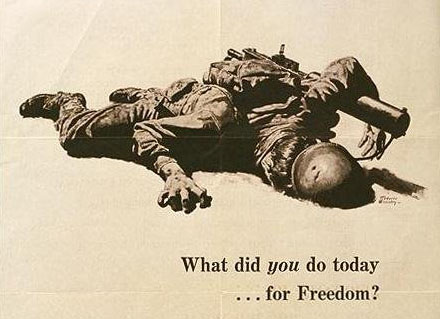

Do Something, Even if it's Wrong

WW2 recruiting image.

In our basic infantry training it was constantly drilled into us that we should "do something, even if it's wrong". This rule applied, no matter what the situation or circumstance. The rule was intended to emphasize that it was better to do the wrong thing than to do nothing. Doing nothing when confronted by the enemy was the worse thing possible. Even doing the wrong thing might turn out to be the best thing, because the enemy would not be expecting it.

This episode is about the time that an officer seized upon a golden opportunity to demonstrate this point to us.

We were in the hand grenade-throwing phase of our training. We had been drilled in the proper way to throw grenades, but using dummy grenades. Now we were at the hand grenade range for our first experience in throwing real, live, grenades.

They were running one squad at a time through the training procedure. There were a total of twelve men in a rifle squad. So, for safety, there were thirteen foxholes previously prepared for participants to jump into after the grenades were thrown. Twelve holes were in a line, one for each man in the squad. One hole for the Range Officer was located to the right of the enlisted men's line of holes. It was also a few feet in front of the enlisted men's line of holes so that he could observe each man to see if he was using the "proper" technique and "form". Under the procedure, all twelve grenades would be thrown simultaneously.

The procedure required four specific commands from the Range Officer. They were:

- "Stand". At this command, every soldier was to take up his throwing stance that called for both hands to be in front of the thrower and below his waist. The grenade must be in the throwing hand with the safety lever against the palm. (If the fingers hold the safety lever, it could be accidentally released prematurely if the thrower relaxed his grip on the grenade.) The ring that is attached to the safety pin must be well in the grasp of the index finger of the non-throwing hand.

- "Pull pin". At this command, the soldier simply pulled the safety pin and remained motionless with both hands still below the waist while the Range Officer checked each man to determined that his pin had been properly pulled, and that the soldier was still maintaining proper form.

- "Prepare to throw". At this command, the soldier must bring his throwing arm up and behind him in the proper manner. The non-throwing arm must be extended horizontally and pointing at the intended target, and with the fingers also extended. The soldier must hold this pose while the Range Officer checked each man for proper form and technique.

- "Throw". At this command, the soldiers finally get to throw their grenades simultaneously and jump into their foxholes for protection. At this point, the Range Officer also jumps into the hole prepared for him.

When my squad was having its turn at demonstrating its throwing skill, we only got as far as the "Pull pin" command. After pulling the pin on his grenade, one of the soldiers lost confidence in the safety provided by the safety lever. He promptly threw his grenade. When the grenade is thrown, or released, the safety lever flies off, permitting the firing mechanism to strike a percussion cap, which in turn, ignites the fuse. At this point the grenade will explode in five seconds.

When the percussion cap is struck, it makes the same sound as a cap pistol. Hearing the cap pistol crack of the other soldier's grenade, the rest of us immediately threw our grenades and leapt into our holes without awaiting further orders from the Range Officer. The first grenade exploded, and two seconds later, eleven more exploded almost as one.

When I, and the other soldiers, raised our heads above the ground, there stood the Range Officer outside his hole. He had not moved. Not expecting what happened, he was caught off guard and had done nothing. By some miracle he had not been hit by one of the fragments from the twelve grenades.

I saw this incident as an excellent example of the "Do something, even if it's wrong" rule. The eleven soldiers, who threw the grenades after hearing the firing cap of the first grenade, did what was wrong under the range procedures, but were much safer than the Officer who did nothing.

Wheeet!-Wheeaa!

I had been in the army about two weeks when the following events occurred. I, like a few million others, was a civilian one day and a serviceman the next.

I was in the army but had not yet made a full transition to soldier. I was referred to as "soldier", but was not yet a soldier. That came later.

On this day I, and another "soldier", were on garbage detail. A corporal, who drove the truck, was in charge of the detail. We would pull up to the garbage rack outside each mess hall in the regiment. The cans were loaded onto the truck with all of their contents. When the truck was full, the cans were taken to the camp dump and emptied.

We had just stopped at this mess hall next to one of the camp's main roadways. I had jumped out of the truck to hand cans up to the other private who stayed in the truck when I heard a large number of marching feet. I turned my back to the garbage cans to see what was going on. Well, I saw at least 40 WACs (Women's Army Corp) marching four abreast (no hidden message intended) marching toward where I was. They were being led by a lady colonel who counted cadence occasionally to keep them in step.

They were all officers of every rank from second lieutenant to major. They were dressed in cotton olive drab fatigues. Around their waists was a regulation army cartridge belt which supported a canteen of water on their hip. The cartridge belt gathered their uniforms in at the waist, thus accentuating their already hourglass figures. I being a guy found this to be very pleasant to watch.

Now, in those days it was quite common for guys to whistle approval of a cute chick. It was considered a way of paying a compliment. Well, with me being still more civilian than soldier, I could not resist. As the marchers were almost in front of me, I let out one of my very best Wheeet!-Wheeaa! whistles. I watched the ladies a few more seconds and then turned to pick up one of the garbage cans. When I turned, I came up against a body in my path. My eyes were about level with the middle of his chest. I looked almost straight up and saw a very angry one star general looking down at me. I suddenly felt two feet shorter than I already was. I took one step back and attempted a very awkward salute, which the general ignored. He asked, "Private, who is in charge of this detail?" I replied, "The corporal in the truck, sir!"

The general turned toward the cab of the truck and ordered, "Corporal, stand down, now!" The corporal sailed out of the truck and saluted the general. Without acknowledging the salute, the general gave that poor corporal the chewing out of his life. He told the corporal that if he could not maintain proper discipline over the men under his command that he would pull his stripes and pass them on to someone who could.

The corporal took his chewing like a man and never took it out on me. I just wanted to crawl away and hide.

6X6X6

I entered the Army March 12, 1943, at Camp Blanding, Florida. I and my brother, Frank, were sworn in together and then sent to Fort Jackson, S.C., for basic infantry training. We were assigned to the 106th Infantry Division. I was in the 422nd Infantry Regiment and Frank in the 424th.

Prior to Pearl Harbor, our army had been reduced to a mere token of a fighting force. Too many of our citizens would not lend support to a strong defense. After all, we had two oceans protecting us. Ha!

According to www.history.army.mil/documents/wwii/ww2mob.htm: Actual active army strength, April 1940, was 230,000, and actual army strength on 31 December 1942 was 5,397,674 with a goal of 8,800,000.

Because of the great and sudden need for combat troops, existing divisions were not in sufficient number and several new divisions were commissioned. The 106th was one of those divisions. Because there were so few trained soldiers, regular army soldiers were reassigned to other divisions throughout the country to act as a nucleus training cadre. As a result, about 90% of the training cadre was made up of new inductees. The ones who enlisted earlier were selected to train those who followed. The greatest deficit was in trained commissioned officers. It was a sort of blind leading blind scenario.

I write the foregoing to provide an understanding of the setting and situation under which the following experience occurred. One can easily see that there could be a professionalism deficit under such circumstances. I will add that, by the time basic training was completed, we looked and acted like real soldiers.

The following took place toward the end of the first month of basic training. The division's Commanding General decided that the enlisted men were far too negligent in showing proper respect to commissioned officers i.e., there was not enough saluting going on to make him happy. His solution was to detail "saluting police" to catch and report infractions. Of course, these "saluting police" were junior commissioned officers (1st & 2nd lieutenants). Since most infractions took place during off-duty hours, the officers had to perform these duties during their otherwise free time. Complicating matters more, the officers were assigned a quota that they had to meet each day before they could be free to do other things more enjoyable.

Well, we enlisted men were aware of the general's campaign and were doubly motivated not to be caught. One, we did not want the punishment that followed being reported. Two, we did not mind if the officers were up past midnight trying to meet their quotas. It was not long before the officers began working in teams to set traps for us.

One Sunday afternoon I was returning from visiting my brother in his barrack. I was passing through a little park area that had several shade trees and benches scattered about. As I was approaching one of these benches located about twenty feet to the right of the sidewalk I was on, I noticed a soldier sitting on the end of the bench, but not in the normal fashion. He was turned at 90 degrees to the normal sitting position, and with his back toward me. Well, I was immediately alerted that this might be an officer, but could not be certain at first. As I got closer, I saw that it was an officer, so I intended to salute him as soon as I was in a position that he could see me and could acknowledge the salute. I kept my eyes on him constantly hoping that he would turn my way, but he did not. I waited until I was just a little past him so that he could not help but see me. I then turned in his direction and rendered the required courtesy, which he reluctantly acknowledged.

I then turned to continue on my way and, after two or three paces, I heard a loud "soldier!" from behind me. I turned around to see another lieutenant stepping out from behind a tree that had been on my left. While I was distracted by the officer on the bench, I had bypassed the one behind the tree without saluting him. I did salute him after he stopped me, but it was too late.

He already had his pad and pencil out and was demanding my name and the company that I was from. I protested the entrapment, but to no avail. I was reported and, the following Sunday afternoon, my First Sergeant ordered me to dig a 6X6X6 behind the company supply building. (A 6X6X6 is a hole six feet square and six feet deep. By the way, I was a towering 5' 3" at the time.)

The general's campaign did little to promote respect for our officers. We understood their plight, and had some sympathy toward them. All sympathy vanished when they began to cheat. We did respect the rank and the responsibility that went with the rank, but not the man.

The sergeant had already marked off the 6'X6' square in which I was to dig, so with shovel in hand, I began. After an hour or so I had dug about half of my six-foot depth requirement when my shovel hit something metallic. I got down on my knees and dug around the object with my hands. It turned out to be a real live fragmentation hand grenade, not a training grenade.

I took the grenade to the Company Orderly Room to show the First Sergeant, thinking that he would allow me to dig in another location. Instead, he ordered me to continue digging. He wanted to know what else might be there. I pleaded with him to let me fill in the hole and I would gladly begin another 6X6X6 at another location, donating the work I had already done. I did not win. He ordered me to continue the excavation and to pile everything I found outside the hole.

Within the next two feet of digging I found enough ordinance to over-fill a large wheel barrow. I found another fifteen or twenty hand grenades, a number of bazooka rockets and mortar shells plus several canisters of machinegun and rifle ammunition. Of course, that two feet of excavation was done largely by hand, and very slowly.

Also, as the hole got deeper, the berm of excavated dirt got higher and steeper, the dirt would slide back into the hole as I threw it out with my shovel. To overcome this, I had to climb out of the hole occasionally and move the berm farther back from the hole. By the time I was about four feet deep, I had difficulty climbing out of the hole. I found an empty wooden crate in the back of the supply room that I dropped in the hole to serve as an exit platform.

The sergeant had provided lanterns for me to see by, and the hole was finally completed about 9PM, having worked non-stop and without the evening meal. After the sergeant checked the depth to see that it was 6', he had me hand up the wooden crate that I had been using to get in and out of the hole, and kindly helped me out. He then tossed a cigarette butt into the hole and ordered me to bury it. There is an army regulation somewhere that prohibits work details as punishment. The detail must have some legitimate purpose. Burying the cigarette butt was his justification for having the hole dug.

It was nearly midnight when the backfilling was completed and I could go to my barrack, hungry and exhausted, where I slept like a rock until 5:45 AM, when we were awakened with the usual lights on accompanied by the sergeant's loud whistle to begin another week of training.

To my knowledge, they never determined when or why the explosives were buried there. My guess was that there had been a Supply Sergeant involved in some shady dealings in military hardware and had to bury the evidence prior to an audit.

Shell Holes and Bomb Craters

There are three types of holes made by bombs, rockets, mortar shells and artillery shells.

Type I Hole: No hole

Now, "no hole" sounds like a very good thing, but really it is not. No-holers are the worst kind because they produce a much wider dispersion of shrapnel. No-holers are normally produced in three ways. One way is by fuses set to explode a certain height above ground. Another way is when, in a forest, the shells strike tree limbs and explode prior to reaching the ground. No-holers also occur in rocky, mountainous terrain. Shells exploding on rocks do not make holes, but they do produce a maximum of shrapnel in all directions. This type is especially vicious because one cannot dig a hole in rocky terrain. All three No-holer types should be avoided whenever possible. All are equally effective on the target.

Type II Hole: Small narrow hole

These are the best kind and are most favored by those on the receiving end. They are produced by what is termed "dud". While these are the most favored, it is also very wise to move away from one as fast a possible. You never know when a dud will change its mind.

Type III: Relatively large bowl-shaped hole

These are made by bombs, rockets, mortar shells and artillery shells that strike the ground and do what they are supposed to do, explode.

The diameter and depth of these holes vary substantially. There are many factors that affect the diameter and depth of Type III holes. The most common factors are:

- Size of the projectile.

- Angle of approach.

- Condition of the ground that it lands in. Soft, wet, ground permits deeper penetration prior to exploding, thus, creating a deeper and wider hole than if it lands on hard ground. Ground can be naturally hard or it can be frozen.

- Type of fuse. The fuse can be timed for ignition at impact, or it can be set for a brief delay. Delayed fuses are used when trying to penetrate buildings, bunkers, or armored vehicles. When these shells miss the intended target and strike the ground, they make a deeper and larger hole than the so called "point detonation" shells do.

Generally speaking, the larger and deeper the hole, the better the recipient likes it. Deeper penetration results in more shrapnel being absorbed into the ground. Deeper penetration also results in shrapnel flying more upward than outward.

Albert S. Brown |

Infantrymen |

Dull Day |

Foreword |

Do Something, ...

Anzio |

Southern France |

Colmar |

Germany |

Epilogue

Reprinted by permission. |