Staff Sergeant

Albert S. Brown

Infantrymen

Dull Day

Foreword

Do Something,

Even if it's

Wrong

Anzio

Southern France

Colmar Pocket

Germany

Epilogue

Contact Al

dogfacebrownie@gmail.com

![]()

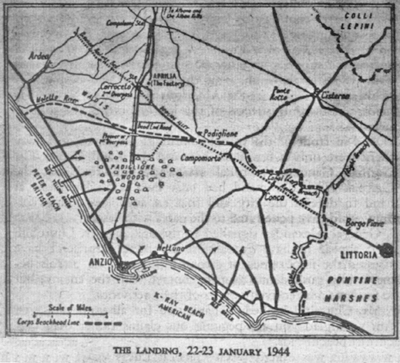

Anzio: Jan-May 1944

A Long, Lonely Night

As stated in other stories of my WWII experiences, I joined the Third Division in Italy on Thanksgiving Day, 1943.

The Division had just been relieved from the frontline and was bivouacked in an area surrounded by a number of artillery batteries that maintained a fairly constant hammering of German positions. This was the nearest that I had been to frontline positions so far.

The next day, I was called for guard duty. There were a dozen or so guard posts in and around the encampment. One was along a ridge overlooking our camp. The ridge was probably five hundred feet above the camp and was about two hundred yards long. It also lay between our camp and the enemy.

The Army has very specific orders pertaining to one's responsibilities while on guard duty. They are in two categories: "General Orders" and "Special Orders". General Orders apply to all posts regardless of location or circumstances. Special Orders apply to a specific post and are special because of that post's location and/or special purpose.

The Special Orders for the post overlooking the camp were:

- To walk the length of the ridge from end to end, back and forth, continuously.

- To be on constant alert for enemy patrols that might try to penetrate our perimeter.

- To watch the sky for possible enemy paratroop drops.

- To alert the camp of a possible air attack.

- If any enemy activity was observed, fire three rifle shots to warn the camp below.

- If there was an enemy ground attack, that post was to be abandoned after giving the appropriate warning, and the duty soldier assigned to that post was on his own to join his unit below.

As you have probably assumed by now, that is the post that I was assigned to. Duty shifts were for four hours. From 6pm to 10pm, 10pm to 2am and 2am to 6am. I drew the 6pm to 10pm shift.

Each guard detail is composed of a number of soldiers equal to the number of guard posts to be manned, plus a Corporal. The Corporal is known as "The Corporal of the Guard." When one shift of guards is relieving another, both Corporals accompany the shift going on duty. The Corporal going off duty goes along so that he can be assured that all of his men get properly relieved.

The trail that led up to the post that I was to guard was very steep and slippery. The old Corporal of the Guard stayed at the bottom of the trail with the other men in my shift, while the new Corporal of the Guard and I made the climb to relieve the man then on duty. It was still light as we made the trip up, but it would soon be dark. I was not real happy with the post that I had drawn, but was determined to make the most of it.

It had been raining a slow, steady, rain for several days and did not show any sign of letting up. Most of the soil in Italy is heavy clay that turns to mud when wet. It is also very slippery. It was very difficult to walk the length of the ridge without losing my footing several times with each trip across.

As I alternately walked and fell, my mind was constantly on my Special Orders for this post. I was especially concerned about number 6). I listened for sounds of possible infiltrators. I watched the sky for paratroopers. For me, every sound was an enemy. Our artillery was booming around me, their flashes lighting the area for brief instants. Often, in one of these flashes, I would think I saw the silhouette of an enemy soldier.

This went on for seemingly endless hours. After I decided that my four hours had passed, I began pausing for a few minutes at the end of the ridge from which my relief was to come, in hopes that I would hear them coming. When no relief came, I began telling myself, that in my impatience for relief, I was letting my mind run in double time. I told myself that if I did not think about the passage of time, it would go faster.

This went on and on until I was absolutely convinced that my time was up, but still no relief. Finally, the sky to the East began to lighten up. This was my confirmation that I had been left to serve three shifts. As 6am and full daylight arrived, I heard voices coming up the trail.

When I met my Corporal, who waited at the bottom of the hill, I asked him why I had not been relieved. His lame, unacceptable, excuse was that he had forgotten that I was up there. I think I knew why he did not come. My first thoughts were to report him to the Officer of the Day, but after having breakfast and more time to think about it, I decided to let it pass. The upside was that the Corporal was not from my platoon and that I would not be going into battle under him. Besides, I only wanted to sleep and put the longest, loneliest night of my life behind me.

This is not the end of the story. About 9:30 am, this Corporal awakened me from a sound sleep and ordered me to get dressed. I was going on guard duty again. This time it was going to be the Battalion Commander's tent. I could see me at my court martial for falling asleep while guarding my Battalion Commander. I respectfully declined the Corporal's kind offer. I told him that I was not fit for guard duty, and that it would be irresponsible for him to give me the assignment.

At this, the Corporal raised his voice and informed me that he was giving me a direct order to get up and to go on duty. If I did not do so immediately, he would report me to the Officer of the Day. I said, "Great idea. Report me to the OD."

He reported me, and before I could fall asleep again, the OD was outside my tent ordering me to come out. I came out immediately and gave the OD my very best salute. He asked why I was refusing the Corporal's orders to go on guard duty. I told the officer that it was because I was unfit for guard duty. I then explained to him that I had just come off the guard post on the ridge after three continuous shifts because I had not been relieved. He asked the Corporal if that was true. The Corporal acknowledged that it was. The OD ordered me back to sleep and left with the Corp oral.

I learned later that the Corporal had pulled that shift guarding the Colonel's tent.

Also , the next day in the chow line, I noticed the ex-corporal was no longer wearing his stripes.

Pete Deanda

I often think of Pfc. Peter G. Deanda, or simply, Pete Deanda, as he was known by the troops.

As I have stated in reports of other events, I came to the Third Division Thanksgiving Day, 1943. The Division had just been pulled from the front. We did not know it at the time, but the Third Division was selected to spearhead an assault landing near Anzio. The landing took place on January 22, 1944. In the meantime, the Division went through very intensive training for the mission. The training included several practice landings from various landing craft.

That two-month period was valuable to me in that it allowed me to learn a lot about combat from the men who had been there. It also gave me the opportunity to really get to know Pete Deanda.

I noticed that Pete was a loner and without close friends in the Company. It wasn't that he was reclusive or standoffish. Actually, I thought that he was very out going and friendly. But for some reason, the men who knew him longer than I, merely responded to him in a friendly way. No one seemed to claim him as a close friend.

He came over with the Division and participated in the landings in North Africa and all battles in Africa, Sicily and Italy up to this time. He had always performed exceptionally well in combat and all that knew him had great respect for him. Yet, he did not seem to have a best friend. It made no sense to me.

I had only been with the Division a week or two when Pete began to cultivate my friendship. I guess it was my small 130 lb frame and baby face that made me non-threatening to him.

Pete was from Tyler, Texas, and immensely proud of it. He idolized the famous Texan. One of his favorite things was to challenge new comers to guess whom Tyler, Texas, was named after.

I soon learned that he was illiterate. He would have me read his letters from his girl friend back in Tyler. He would dictate letters to me to send to her.

Pete was from an Apache father and a Mexican mother. He was very handsome. About six feet tall and perfectly proportioned physically. He had hair that would change from jet black to a very dark auburn, depending on how the light would strike it. He was very proud and always perfectly groomed. He and his uniform were always ready for inspection. He was a very good and disciplined soldier.

All of the above statements about his amicable demeanor and character were true. But, as I learned later, only when he was sober. I say in his defense, that he was sober most of the time. He would only drink when away from camp on leave, or was AWOL.

During this two-month training period, passes were few and far between. About midway in the two-month training period, some of us were granted passes to visit Naples. Pete was one of the lucky ones, or unlucky ones, depending on your point of view.

Pete returned from his night in Naples well past curfew and escorted by two MP's. As a matter of fact, we had already had our daily, before-breakfast, five-mile speed march. We had finished breakfast and were on "police detail" when Pete was brought in. (Police detail is where the soldiers form a line across the Company's camp area and walk along picking up every piece of litter, no matter how small.) The First Sergeant had Pete join in on police detail.

It was then I met the other Pete Deanda. I then understood why it was against the law in Texas to sell alcoholic beverages to the Indians.

Pete was mean and surly. He kept trying to pick a fight with anyone and everyone. He screamed for everyone to shut up whenever anyone spoke. Then, when everyone kept quiet, he shouted at us for being too quiet. I was stunned at his behavior. But I understood why the other men never got close to him.

The only way to deal with him was to stay out of his way until he sobered up. Once he was sober, the amicable Pete returned. He would apologize to everyone for his behavior. And he would cry big tears. He cried because he was ashamed of his weakness. He once told me that a good Brave did not lose control of himself, and that his Father would be very unhappy with him.

Pete and I continued in our close relationship. I found a lot of good in him. Also, he was a good man to have on your side in combat.

Our preparation for the Anzio invasion continued. Pete stayed out of trouble until January 20, 1944. He went AWOL after the evening meal. When we were rudely awakened about 3AM, January 21st, to stand muster, Pete was not there.

At this 3AM muster we were instructed to prepare our packs for combat, strike tents, leave our duffle bags at a specified point for pick up by our Quartermaster, and to be ready for breakfast at 4AM. We were to load on trucks at 5AM for transportation to an unspecified destination. From our special training we knew we would soon be aboard a ship. We just didn't know its destination.

When Pete was reported AWOL, Captain Greene, our Company Commander at the time, announced to all assembled, that, if Pfc. Deanda missed this upcoming event, he would spend his next twenty years in prison doing hard labor. We all knew that he meant every word.

Our platoon leader asked me to prepare Pete's combat pack and to get his duffle bag of personal belongings to the pick up point. He then persuaded the Company Commander to leave me behind to watch for Pete. I had to come with the cooks on one of their jeeps with or without Pete. The cooks would be last to leave because of the time it would take them to pack up all the stoves and other cooking paraphernalia.

I was happy that Pete was going to be given a chance. I gladly put his pack together and gathered all his personal belongings into his duffle bag and dragged his and my bag to the pick up point. I got his mess kit out and filled it with the morning's bill of fare, snapped the lid on tightly and hoped that he would show in time to eat it.

Trucks arrived on schedule. Everyone except the cooks and me loaded onto the trucks and, shortly after 5AM, Company H, 30th Infantry, moved out for the docks at Naples harbor.

I kept my eyes on the ridge that Pete would be coming over if he returned. I guess a half an hour went by, but no Pete. I could see by the progress they were making that the cooks would be ready to leave within another ten or fifteen minutes.

About that time, in the gray light of dawn, I saw Pete coming over the ridge. I ran to meet him. He was drunk. He looked at where the camp had been and asked what was happening. I told him that he was going to prison if he didn't shape up.

I told him the deal. I helped him with his pack and rifle. We got in the back of one of the jeeps where Pete made a stab at eating breakfast as we bounced along toward Naples harbor.

When we arrived at the dock, I helped Pete from the jeep, and we headed for the area where I had been told Company H would assemble. In another ten minutes, Pete and I were back with our Company.

Naples harbor was a busy place. There were more ships anc hored in the harbor than I could count. Every foot of docking space was being utilized by a variety of ships. Everyone had his orders and deadlines to meet. Troops and vehicles were all vying for maneuvering space on the dock. Troops had to be loaded of course. But the supplies t hat they were going to need also had to be loaded.

As we were pushing our way toward the LST that we were to board, a truck w as inching along very slowly. The driver was being very careful not to endanger the troops that practically surrounded his truck. I saw Pete, still wobbly on his feet, very close to the truck's left front fender. Pete moved a little sideways and encountered the truck. Pete was in his usual mood when drunk. He blamed the driver for crowding him. In a burst of anger, Pete opened the driver's door, pulled him from the truck and began punching him hard with both fists.

Several men, more his size than I, moved in to stop Pete. It took about four men to hold him. A First Lieutenant that was nearby moved in and ordered the men to restrain Pete until the MP's could take over. With that, Pete freed his right arm and flattened the Lieutenant on the spot.

When the MP's arrived, Captain Greene instructed them to put Pete aboard the LST to be dealt with later.

Finally, after we were all loaded, I wanted to check on Pete. I found him in his bunk crying so loud that everyone in the compartment could hear. Huge tears flowed down his face. He wanted me to help him find the officer that he had punched so that he could apologize.

After Pete was fairly sober, he was summoned before the Company Commander. Capt. Greene told him that he was going to give him one last chance. But, if he messed up again, he would be court-martialed and that Capt. Greene would charge him with every past breach of discipline on his record. The charge of striking an officer would be a very serious charge. He would be dishonorably discharged, and would definitely be in for some prison time.

Well, Pete made the landing and participated in the Beachhead fighting for about three months until one night, Pete and a shell fragment met. His wound was severe enough to end his career as a soldier.

After release from the hospital, he was honorably discharged and returned to Tyler, Texas.

Pete Deanda's wound was a blessing. It saved him from disgrace and prison. It would have been impossible for him to not foul up again.

My First Day

A few minutes before 2 AM on a dark moonless morning, January 22, 1944, many assault boats moved at full throttle toward a beach near Anzio, Italy. The sea was very calm. I was in one of those assault boats. Not only was this to be my first assault landing, it was to be my first day in combat.

I was the number three gunner in a water-cooled machinegun squad. My combat load consisted of a canister of water for cooling the gun and a canister of ammunition for the gun. Other members of the squad carried two canisters of ammo each for the machinegun. The canister of water and the canister of ammunition weighed 20 pounds each. In addition to this 40-pound combat load, I also carried a nine-pound rifle with ammunition for it, entrenching tool, combat pack with blanket, shelter half, extra clothing, personal items, rations for three days, and a gas mask. My total load had to be eighty pounds or more. My body weight at the time was 130 pounds, and my height was five feet four inches. You could say that I was not dressed for swimming.

We were in LCVP's, Landing Craft Vehicles and Personnel. These craft carried up to forty men. The craft I was in hit a sandbar about 100 yards from shore. We were all thrown forward as the craft stopped abruptly. Being in the front, I was slammed hard against the forward bulkhead, that was also a ramp when dropped, and was a reluctant cushion for the men behind me.

An LCVP is rectangular in shape and sits very deep in the water when fully loaded, as it now was. Because of this rectangular shape and deep draft, it creates a very large following sea, or wave. As this following wave passed under our craft, it lifted us off the sandbar. Our coxswain was prepared for this lift and immediately gunned the engine to full throttle. The boat lunged forward twenty or thirty feet, but not enough to clear the sandbar. Our craft was now stuck with its stern on the sandbar and its bow over deeper water. The coxswain made several full throttle efforts to move forward, but it was useless, the boat was stuck fast. The coxswain dropped the bow ramp and ordered everyone out.

When the ramp dropped, the entire front of the boat was open to the sea. A huge wave rushed in, and in one or two seconds the water was above our knees.

As mentioned, my position was in the very front and on the port side. As I stepped off the ramp, I was completely submerged. My helmet was lifted off my head as I went under, and as I learned later, flipped over and floated away. I know this because my squad leader found it when he went back into the sea looking for me.

By tiptoeing, I was just barely able to keep my mouth above water, but had almost no traction for forward progress. The taller men behind me were crowding me in their haste to get ashore, making it difficult for me to maintain my balance. I turned to my left to let them pass, and in so doing; I stepped into a hole that put the water about two feet above my head.

There I was, in deep water and weighed down with a heavy combat load. It never entered my mind to drop the ammunition and can of water. The can of water is especially important to the machinegun. The gun cannot fire long without water for cooling. Besides, I still would not have been able to swim if I had released the ammo and water cans.

I knew that I was in big trouble at this point, and that panic was now my enemy. I must not panic! Some people say that when you are in this kind of a fix, your entire life passes before you. Well, in my case only a small portion of my past came into play.

I grew up in northwest Florida and our family took frequent outings to swim in the Gulf of Mexico. Before I was able to swim, my favorite thing to do was to work my way into water beyond the breakers, and then, I would continue moving out to a depth where it was necessary to tiptoe to permit my mouth to be above the crest of the waves. From there I would crouch in the trough and leap toward deeper water. The momentum of the leap would carry me over the crest and a little farther out. By repeating this maneuver, again and again, I would reach a depth where, if it were calm, the water would be over my head. I would then do what I called, "ride the waves." In the trough my feet would be on the bottom so that I could crouch and leap, with my momentum carrying me over the crest. This allowed me to be with kids much taller than I.

I cannot say that I consciously remembered the boyhood pastime. I think my reaction was just instinctive, but I am sure that it was an instinct borne of that boyhood fun. Without hesitation, I dropped into a crouch and leapt up and forward as hard as I could. The momentum of my jump carried me to the surface for a quick breath before being sent to the bottom again, where I crouched and leapt to the surface for another quick breath. I repeated this procedure again and again, still clinging to all my equipment, including the water and ammunition canisters. With each leap I made a little progress toward shore.

I finally reached a depth where I could keep my mouth above the surface. I just stood there on my tiptoes filling my lungs with much needed air and thinking how fortunat e I was that the water was very calm that morning. Had there been waves of any consequence, I doubt that I would have made it.

After a minute or two, I regained enough strength to work my way into shallower water and finally wade ashore. As I drew near to where the other men from my squad were waiting on the beach in the darknes s, I heard my squad leader, Cpl. James Pringle, telling them that he had found my helmet floating upside down near where I went under, but that he had n ot found me. Then I heard Pfc. Leonard Troutman, number one gunner, exclaim, "Oh my god, he had the water can!" In response to Troutman's concern for my good health, I wanted to announce my arrival by dropping the water can on his foot.

I did forgive Troutman. His concern for water to keep his gun operative was well founded. He and all the men were overjoyed that "Brownie" had not drowned as expected.

I had been the only man not present when the squad checked off on the beach. Cpl. Pringle went back into the sea to look for me. That is when he found my helmet. He told me that he had even felt for me with his feet.

Now that everyone was accounted for, we moved out to a pre-determined assembly area where our Section Leader, Sgt. Marcantel, reported to the Commander of the company we were to support that day. We were ordered to follow close behind the riflemen and to be ready if needed. The riflemen moved out with First Section, First Platoon, Company H, following closely behind. Thus began my first day of combat.

Daylight found us, still wet from our dunking in the Mediterranean, moving cautiously through a forest. Sgt. Marcantel, armed with a carbine, was walking in a crouch like an Indian stalking his game. Sgt. Walla, Squad Leader of the Second Squad, said, "Hey, Marcantel, what are you going to do if a bunch of krauts jump up in front of you?" Marcantel replied, "I'll empty this carbine into the lot of them."

Before I give Walla's reply, you need to know that the carbine was fed ammunition via a clip that was inserted from the underside of the carbine. The clip held fifteen rounds. On the right side, just in front of the trigger guard, were two buttons. One was the safety release. The other was the clip release. Press the clip release button and the clip will drop out.

Walla replied, "How many do you think you will get with one shot"? At that, Marcantel, and all that were in on the exchange between them, took a good look at his carbine. There was no clip in it. The clip of ammo was still back at the assembly area where we began. Intending to take his weapon off safe, Marcantel had pressed the wrong button and ejected the clip.

To compound matters further, the carbine was still on safe and would not have fired anyway. Sgt. Macantel took the ribbing that followed in good spirit. This broke a lot of tension as we continued forward. It helped me a great deal. I learned that you could take humor into battle if you chose to.

By mid-morning we were moving through an open field. The sun had dried our clothing completely. I was carrying the machinegun at the time. It was common practice for us to exchange loads with the number one and two men to give their shoulders a rest. Number one carried the tripod. Number two carried the machinegun. I was number three, as stated earlier, and had traded with number two to give him a break.

Suddenly, there was shooting ahead of us. The call went out for the machineguns to come forward. Cpl. Pringle and Pfc. Troutman dashed forward to a shallow ditch where Pringle wanted the gun set up. I followed close behind with the gun. Troutman set the tripod where he wanted it and I placed the gun on the tripod and moved to one side so that the number two gunner could take over and assist with the firing of the gun.

To my surprise the number two gunner had hit the ground when the shots rang out and had not moved. The rest of the squad behind him had followed suit. They were all flat on the ground. I called to soldier X (I choose not to use his name.) to bring the water can and ammo forward. But he was frozen and could not move. I ran back and took the water and ammo from him and told the others to get their ammo up to the gun position. I returned to the gun and helped Troutman prepare the gun for firing.

We never knew what the shooting was about. We were never given a target to fire on and in a couple of minutes were up and moving again. Cpl. Pringle changed my assignment to number two gunner and moved soldier X to last position in the squad. Soldier X was transferred to Battalion Headquarters Company the next day. So, before noon of my first day, I had moved up one position in the Squad.

In fairness to soldier X, I must report that he overcame whatever it was that caused his inaction that morning. He later volunteered for the Battalion Battle Patrol and served honorably to the end of the war.

My First Foxhole

Note: Foxholes are not for foxes. They are for soldiers. That's just what they are called.

Defensive positions on one of the "wadi" at Anzio.

Slit trenches and foxholes can be seen on the upper bank. The bridge and

the road further on have been destroyed, but the obstacle is spanned by

a temporary bridge. (photo by Jack Cole)

January 22, 1944, we landed on the shore of the Mediterranean Sea near Anzio, Italy, at 2AM. (See "My First Day") The Germans were caught by surprise and the landings were almost unopposed. We met very minor resistance as we moved inland. We knew that the Germans would be sending opposition forces as rapidly as possible. But, not knowing the enemy's capabilities or timetable, we were prepared for contact at any moment. We spent the entire day moving cautiously forward until, by nightfall, we were five or six miles from the beach where we had landed.

Soon after dark, we were ordered to dig in and establish defensive positions. Leonard Troutman and I began to search for a good location for our machinegun. Troutman had arrived from the States just a few days ahead of me. This was going to be our first foxhole under combat conditions.

We noticed a concrete wall about two feet high that was well enough in line with the other defensive positions being established. We decided that the wall would be a good protective palisade to fight from if we were attacked. The wall should stop small arms fire with no problem, and the machinegun could easily be set up high enough to fire over the wall. It seemed like a winner, so we began to dig our hole as close to the wall as practical.

We had barely begun when we became aware of an unpleasant odor. There was a masonry outhouse about ten feet from our hole, but that was not what we smelled. Investigating in the dark, we discovered that the wall we were digging behind was one of two walls at the edges of a concrete slab about fifteen feet square. The walls met at one of the corners of the slab. Stored on the slab, and against the two walls, was animal manure.

With this discovery, we considered digging in another location. But, the anticipated protection from small arms fire outweighed having to put up with the odor. Anyway, we figured that we would get adjusted to the smell after awhile. So, we stayed with our first choice and continued digging.

The ground was very hard, and diggi ng was difficult. We would break loose an inch or two at a time with our pick and then remove the loose material with our shovel. After an hour or more we were only about a foot deep. But, the real problem was that water was beginning to seep into the hole. Water would splash on us every time the pick struck the ground. But, so what, if it rained we would be wetter than from the splashes. Besides, there was the protection from small arms fire to be considered. So, we continued digging.

The water made digging more difficult. The clay soil that we were digging in became very plastic and gooey after we hit the layer where the water began. The wet clay would stick to the pick and we had to pull it off with our hands. Progress became even slower. But that was OK. Once the hole was completed we would have protection from small arms fire. Also, we would have our own private john with the outhouse only ten feet away. So, we kept digging and bailing water.

Finally, after about two hours, we were barely two feet deep, and water was coming in even faster. We decided that, because of the water, we would not be able to make this a hole that we could stand up in. But that was OK. We would just lengthen it to what the army calls a slit trench that we could lie down in. We would be below ground for protection from artillery and mortar shell fragments, and we still had the wall for protection from small arms fire. So, we kept digging and bailing.

It must have been about 2AM the next morning when we decided to call it quits. The hole was long enough, and we both agreed, grudgingly, that it was deep enough. Besides, we didn't have enough energy left to dig another grain.

January nights in Italy can be very cold. We discovered this once we stopped the vigorous exercise of digging. We bailed the water from the hole, wrapped ourselves in our blankets, and settled in for what was left of the night. We both fell asleep almost immediately.

At the crack of dawn we were jarred awake by a bang as loud as a thunderclap. My first thought was that one of our tanks must be close to our hole and had fired at something. I looked around. There was no tank in sight. I saw other guys from our platoon with their heads up looking around as puzzled as I was.

Then it happened again. This time I knew what it was. A German Tiger tank was firing at a road intersection about five hundred yards behind us. Our "private" john was directly in line with his target. The shell passed no more than a foot above the outhouse. I happened to be looking in that direction when the shell passed. I saw the red tile shingles jump in its wake.

When a high velocity shell passes that close, it makes the same shark crack that the gun makes. It's as though the cannon is right there, not several hundred yards away.

The firing continued for at least half an hour. It fired one shell every minute or two. But this was not our only concern. While we had slept, the hole had filled with water. Our blankets and clothing were completely soaked with foul smelling water. We were also shivering in the cold morning air.

We wanted to get out of the hole to bail it out and to wring the water from our blankets, but did not feel safe getting out of the hole with 88mm shells shaking the outhouse every minute or two. So we just laid there, speculating as to what would happen if the Tiger lowered its aim by a foot and hit the outhouse. We concluded that we would get a lot of concrete chunks along with shell fragments in our hole if that should happen.

I then began to wonder what would happen if the Tiger's crew spotted our positions and put a few rounds in the manure pile. Or, even worse, what if a shell struck our little two-foot wall? I figured we would get even more concrete and shell fragments than if the outhouse were hit.

Finally, after ten minutes had gone by without a shot being fired, Troutman and I decided to get out of the hole. First we bailed the water out. Then we wrung out our blankets. All this was done while lying down, because we were afraid that we would be seen if we rose higher than the wall. Next, we stripped and rolled up in our blankets while we wrung out our clothes. After putting our clothes back on, we left the blankets spread out on the ground to dry in the sun that was now up pretty high.

Not wanting to get back in the hole unless our lives depended upon it, we lay spread-eagle on top of the ground next to the wall to soak up the sunshine.

About mid-day we got the word to move out to another location. Before leaving, I examined the slab and its pile of manure. I discovered that a hand pump was located next to the other wall so that water could be pumped over the wall and onto the manure. It was obvious that the pile was kept wet intentionally. Water was constantly draining out of the manure and over the open edges of the slab and was finally absorbed into the ground. This had probably been going on for several generations. I now knew the source of the water that was in our hole.

Troutman and I took a good dip, fully clothed, in the first stream that we came to. This got most of the odor from our clothing. We were cold and wet most of the day, but by sundown were nearly dry again.

That was a miserable experience. But, most of all, it was a very valuable learning experience. Never again would I dig within a hundred feet of a manure pile or building if I had a choice.

A Darby's Ranger, Almost

I entered the US Army in March of 1943. I received my basic infantry training in Fort Jackson, S. C. After our basic training was completed, we were placed in the Army's replacement pool and began our journey to assignments to various combat units overseas. This involved processing through Replacement Depots in Africa and Italy.

As we were processed through these depots, we would become more-and-more separated from the friends we had trained with. In an effort to stay in touch, we would meet in front of the mess hall at the end of each day, at each new camp. By the time we reached the replacement camp in Italy, there were about ten of us that were still together. That first night in Italy, knowing that our next assignment would be a combat unit, we made a vow to do everything we could to be assigned to the same unit.

The next morning (being a Private) I was assigned to work in the mess hall (known as KP duty) and was not finished until about 9PM that night. As soon as I was off, I went to see my friends and learned that they had volunteered to join a Ranger Battalion. In keeping with our vow, I immediately reported to the First Sergeant and asked that I be assigned to the Ranger Battalion that my friends had joined. The sergeant explained that he had no control over that. An officer from the Darby's Rangers had recruited my friends. He told me that the officer would be back the next day, and that I could sign up for the Rangers then. The Rangers took their name from their Commanding Officer, Colonel William O. Darby.

The next morning, at first muster, the First Sergeant read an assignment list for replacements being sent to the Third Infantry Division. My name was on that list.

When we were dismissed, I reported to the First Sergeant and asked that I be taken off the list so that I could join the Rangers. He said that the orders could not be changed and that I would be sent to the Third Division. I was assigned to Company H, 30th Infantry Regiment, Third Infantry Division. That was in November of 1943. I served with the Third Division for the remainder of the war, ending in Salzburg, Austria, in May o f 1945.

Portions of the above are important background for the following story.

The Third Division was one of two divisions to make the assault landings near Anzio, Italy, on January 22, 1944. The Anzio Beachhead landing was considered a success at the beginning. But, the number of ships available for our support was limited because of Prime Minister Churchill's insistence that all but a limited number be sent to England to prepare for the Normandy Invasion. Because the number of ships was limited, th e Germans were able to build up opposition forces faster than could we. They had us outnumbered by the fifth day. This prevented the Allied Forces from expa nding the beachhead immediately.

By January 30, 1944, when this story takes place, the Germans were well prepared for our forthcoming attacks.

The Allied forces planned a major attack to begin in the early morning of January 30th. The initial objective was to take and hold the town of Cisterna di Littorria, which was about a mile in front of our current defensive positions.

Two of Darby's Ranger Battalions were to move by stealth through the German lines to be in positions behind the enemy to aid elements of the 3rd Division in a frontal attack at daylight. These were the 1st & 3rd Ranger Battalions, the Ranger Battalions that my friends had joined.

I was manning a machinegun next to a bridge over which the Rangers would pass as they moved out for their mission. The Rangers began coming past my position about 0100. I got up on the road and walked with them for a short distance, looking for my friends. I did find two of them and was able to wish them success.

It was later learned that the Germans were aware of our plan, and permitted the Rangers to pass without opposition. They then formed a circle of infantry, tanks and artillery around them. At daylight the Rangers stormed out of a streambed where they had been waiting and were immediately engaged by the Germans. They were caught in a crossfire of small arms, tank and artillery, all at pointblank range.

From our positions we could see the smoke and explosions but could do nothing to help. The Rangers fought desperately and held out until almost mid-day.

Efforts to come to their rescue were blocked by the enemy's superiority in men, tanks, and artillery. The 4th Ranger Battalion participated in the attempt to break through the Germans' defenses, and was so decimated that it was no longer a fighting force.

Of the 780 men in the 1st & 3rd Rangers, only seven returned.

Darby's Rangers were written off and never reactivated.

It was very difficult to watch and know that my friends from basic training were being killed without a chance. Had I not been put on KP the day they joined the Rangers, I would have been there with them.

Koppelschloss

At our briefing, after boarding the LST in Naples, Italy, we were told that we would be awakened at midnight to load into LCVP's for a 2AM landing on an undisclosed beach. We were advised to get as much sleep as we could.

Following that advice, I decided to hit the hammock about 8PM. I was, of course, very anxious about coming events. I had not yet been in combat and did not know what to expect or how I would perform.

I was not given to praying often, but decided that maybe I might try one. My prayer was a very selfish one. I was to be the only benefactor. I then climbed into my hammock to get some sleep. But sleep would not come. The prayer had not relieved any of my anxiety.

I lay in the hammock thinking about home and my parents. I knew that they were praying for me constantly. Then it hit. There are many Christians in Germany. My mother was from Germany. My enemies' parents would be praying for them just as diligently as my parents were for me. Boy, did we have God boxed in!

I decided that frightened, selfish, prayers were not going to get it done. I dialed in again and asked God to scrap my first request. I asked that He not favor me over my enemy, but to help me meet what trials were to come with courage and not be a disgrace. I promised to do my part by using my wits and brains that He had provided. I felt better and fell asleep in a few minutes.

A couple of weeks later, I had my first opportunity to examine a dead German soldier closely. I noticed the impression that was molded into his aluminum koppelschloss (belt buckle). It was an army issue buckle that they all wore. In a circle around the center symbol were imprinted the words, "Gott mit uns", God with us. As I looked at the buckle I remembered my thoughts aboard the LST. I was right. My enemy has as much right of access to God as I. I did not want to ever forget that, so, I removed the soldier's koppelschloss and put it in my pocket. I wanted something to keep me reminded that my enemy and I were the same. Only the uniforms were different. I also wanted something to keep me from hating him. I would kill if I must, but I did not want it to be driven by hate.

I carried the koppelschloss in my right-front pocket from that moment on, until the war was over. I put it with my personal things and brought it home with me. It remained with my war souvenirs until May of 2001.

Jo and I were planning a trip to Europe to follow my trail in the war. In my planning, I learned of several annual events and ceremonies that took place in Europe at different times of the year. Other Third Division veterans had participated in them and told about them in our Society newspaper.

There was one of particular interest to me. It was scheduled at a time that would fit into our schedule. It was a memorial service held annually at a monument near Jebsheim, France, near Colmar, where much vicious fighting took place. The monument has three sides, each side representing French, German and American soldiers that fought there. The center of the monument is left open in the shape of a Christian cross.

They meet with the theme "Our Enemies Became Our Friends". They are committed to promoting peace in the world.

I had fought in the battles that took place there and decided that I wanted to attend the ceremonies. In writing to various people in France and Germany, I made contact with a German who was in the German 19th Army that we fought against from the shores of France, up the Rhone Valley, across Germany and into Austria.

He seemed to be a very nice man and I wanted to meet him. He told me that he would be at the ceremonies. I decided that I would take the koppelschloss with me and give it to him. It was time for it to go back home.

At the ceremonial dinner following the ceremonies at the "Cross at Jebsheim", which is what they call the monument, I gave Albrecht Englert the koppelschloss. Through an interpreter, I explained how I took possession of it and why I had kept it. I wanted him to keep it on behalf of the soldier that wore it.

Albrecht was very pleased to accept the buckle, and in return, he removed a pin from his lapel and insisted that I take it. The Commander of the 19th Army had awarded the pin to him. It was for some honorable deed that he had performed in the war. I did not want to take something of that nature, but he would have it no other way.

Albrecht and I correspond regularly. We have exchanged a few experiences from the war.

Albrecht was a radio operator in the 19th Army Headquarters. In that capacity, he was privy to many historic al events as they unfolded. One story that he shared with me was his part in saving the lives of a group of fairly high-ranking German Officers.

The incident took place a few days before the official surrender on May 8, 1945. This group of officers, appalled at the useless slaughter of their men and ours in a cause who's outcome was known, appealed to the top Generals of the 19th Army to permit them to surrender.

The appeal backfired. They were all court-martialed and found to be guilty of treason. They were sentenced to execution by firing squad. However, the court-martial board did not have a uthority to carry out the executions without approval of the highest army command.

They brought their execution request to Albrecht to transmit to the higher command. Albrecht signaled his assistant to turn the transmitter's power to its lowest setting. His transmitter was a 1,000-watt transmitter when at its highest setting. It could reach any station in Germany with no trouble. But, at its lowest setting, its range was just a very few miles.

Albrecht sent the message. The generals stood behind him waiting for a reply. When no reply came back, they ordered Albrecht to send it again, which he did. Still there was no reply. Several more attempts were made, but none brought a reply.

The Generals finally gave up, thinking that perhaps something tragic had happened at the high command headquarters. A few days later, Germany surrendered and there was no legal authority to carry out the executions.

Beyond a doubt, Albrecht's actions saved the lives of those good officers. In so doing, he put his own life on the line. If the Generals had gotten wise, Albrecht would have surely been executed with the officers.

Ringside Seat

In the early weeks of the Anzio Beachhead campaign there was a real battle for dominance of the skies. The Allies finally won that battle and during the latter weeks we were only occasionally attacked by enemy planes.

One morning in February our positions were attacked by a German ME 109 fighter plane. It came in low strafing our positions. After its first run, it climbed to a minimum maneuvering altitude and made a 180 degree turn and was dropping in for another pass. Before he reached our positions a second time, a British Spitfire fighter plane that was patrolling the beachhead came in from above to intervene in the ME 109's plan.

With the Spitfire on its tail, the ME 109 broke off from its strafing run and turned upward to gain altitude and to attempt to get above and behind the Spitfire. Thus began a very exciting dogfight above us.

We had ringside seats to the best show of the day. There is no doubt as to which side we were on. Our dogfaces along the entire front were yelling and cheering for the Spitfire. And, as was expected, we could hear the Germans in their positions yelling and cheering whenever the ME 109 gained the advantage.

This dogfight lasted about ten minutes until finally the Spitfire got into great position and opened fire with all its guns. The bullets were on target and the ME 109 began to trail smoke. Then we saw a parachute open as the German pilot escaped the burning plane.

Of course the cheering stopped on the German side while we dogfaces went wild. My foxhole mate, Chester Borowski, and I were yelling and slapping each other in glee when I changed my gaze from man and parachute to the ME 109. To my horror, the burning plane was coming in on a steep angle and headed dead straight for our foxhole.

I pointed to the plane and Chester saw it too. Our celebration came to an abrupt end. To abandon our foxhole in broad daylight would be suicidal, but staying put appeared to be worse. Just as we decided to run for it, the plane did a barrel roll to the left and crashed about twenty yards from our hole. A hot blast swept over us as the plane exploded into flames.

Our attention was then turned back to the pilot and parachute. Both sides at the front were calling for the wind to bring him to their side of the line. For awhile it was not clear where he would land. Finally a gust of wind brought him down close to our frontline positions. Two riflemen darted out and took him prisoner. The enemy did not fire because they did not want to risk killing their man.

That was a very exciting show that we chattered about for days afterward.

Paint Brushes, Stencils, and Blue and White Paint

(More about Iron Mike O'Daniel)

Lt. General Lucien K. Truscott, commanded the Third Infantry Division in North Africa, Sicily, Italy and during the early days on Anzio Beachhead. A few weeks after the Anzio invasion, the Corp Commander, Lt. General John P. Lucas, was replaced by General Truscott. As Corp Commander, Truscott had command of all units on the beachhead, including the British units.< /p>

General Truscott moved the Corp Command Headquarters from the cellars in Anzio to a two-story farm house within a half-mile of the most advanced positions. From there he could observe firsthand almost the entire front-line perimeter.

He placed General John W. O'Daniel, who had been his Assistant Division Commander, in command of the Third Infantry Division. General Truscott and General O'Daniel were cut from the same cloth, as the saying goes.

Known by his troops as "Iron Mike", General O'Daniel was, like Truscott, a very aggressive leader. He was always close to where the fiercest fighting was. It was not uncommon for his troops to see him in areas of great danger.

Iron Mike knew the importance of maintaining high morale. His motive for staying close to the fighting was to enable him to make better and quicker command decisions, but he also knew that it gave a great boost to morale.

Soon after taking command, Iron Mike made an important morale boosting decision. He acquired paint brushes, 3rd Division Insignia stencils, and blue and white paint. He had these distributed to every 3rd Division soldier with orders to paint the 3rd Division insignia on both sides of their helmets.

With the order, he explained that the 3rd Division was the best damn unit in the US Army and he wanted the Krauts to know that it was "The Blue and White Devils" that were kicking their butts. Normally units prefer to conceal identities lest the knowledge be of advantage to the enemy. It gave us a great sense of pride to know that our commander had such a high opinion of us. It was a tremendous morale booster.

The 3rd Division did not name itself "The Blue and White Devils". That is the name the Germans gave the division back in Sicily.

At Anzio Beachhead, replacement troops would arrive almost daily. The first requirement of each soldier who was being assigned to the 3rd Division was to paint the blue and white insignia on their helmets, with Iron Mike's above explanation. Whenever it was possible, Iron Mike met the incoming replacements and gave them the message in person.

From that beginning to the end of the war the 3rd Division insignia was on our helmets.

Anzio Shep

Normally, we only think of people casualties in a war. Seldom do we measure war's cost in innocent animals.

Hardly a day of combat passed without my witnessing the death and maiming of animals. They were farm animals, wild animals, and household pets. The Germans used a number of horse drawn wagons and artillery pieces. These animals became targets of war, but still were innocent in my mind.

Anzio Beachhead was by far the worst for animal slaughter that I witnessed. For four months, the beachhead perimeter was a fan shaped piece of real estate. It measured about ten miles along the shore and was about eight miles deep at the deepest point.

Thi s area was mostly flat farmland. In addition to the usual assortment of farm animals you expect to find in farm country, was a flock of sheep. The size of thi s flock was estimated at the beginning to be as many as two hundred.

The owner of these sheep obviously was no longer tending them. However, a large sheep dog was still faithfully at his post. We called him Shep. The sheep were forever getting caught in the war's exchanges of artillery and small arms fire.

Whenever the flock was scattered after being caught in our crossfire, Shep would go right to work rounding them up and calming them down. If the sheep got caught in a minefield, Shep would remember the area and would guide the sheep away from it after that.

Weeks went by, the flock grew smaller and smaller, but faithful Shep was still on the job guiding and calming them. And then one day, Shep was no longer seen. Our only conclusion was that he was finally a casualty himself. The sheep, now fewer than fifty in number, began to wander in ever smaller and scattered groups until eventually they were no more.

Somewhere in heaven is a beautiful sheepdog with a CMH medal hanging around his neck.

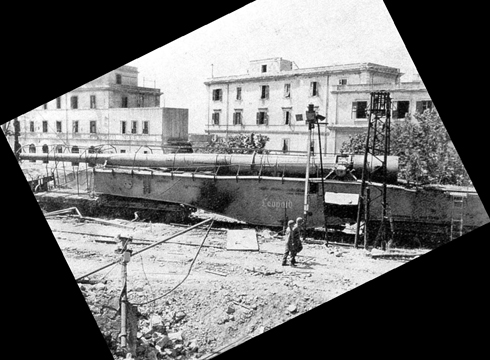

Anzio Annie

Anzio Annie captured by Allies at Civatavecchia near Rome

Almost everyone that knows much about Anzio Beachhead has heard of "Anzio Annie." Unfortunately "Anzio Annie" was not a voluptuous female. It was a very large artillery piece that fired a shell 280 millimeters (11 inches) in diameter. The gun was mounted on a railroad car and was moved in and out of tunnels some twenty to thirty miles from the beachhead. It was capable of hurling a 550 pound shell a distance of 38 miles. Actually, the Germans had more than one of these poised around the beachhead.

The German's had another, even larger, railroad gun that had limited use at Anzio Beachhead. It could hurl a 16" diameter 1,600 pound shell even farther than the 280mm gun. Its use was limited because it could fire only one round per day. It had to be lowered and allowed to cool or the barrel would bend from overheating. Both guns were dubbed "Anzio Annie."

However, it was the 280mm gun that did most of the firing and was more famous. This huge canon was capable of reaching any spot on the beachhead and, during the four- month period that the campaign lasted, few places on the beachhead had not been targeted.

Because of its great range, its projectiles reached a very high altitude before returning to earth. If the beachhead happened to be quiet at the time it was fired, the sound could be heard at the frontline. But, because of the time required for the sound to travel the twenty to thirty miles between the gun and our positions, the projectile was well on its way to impact by the time we would hear it. At night, the flash could often be seen. This provided more warning than in the daylight. Following the sound of firing, we would listen for the sound of the projectile as it climbed higher and higher. It made a soft whispering sound (whooah-whooah-whooah) with small pulsations.

The only way to know if you were going to be in the impact area was if the sound suddenly stopped. If the sound stopped, you were in the impact area. Two seconds after the sound stopped, the shell would impact. We called it the two-second warning. One second to realize that the sound had stopped. One second to hit the ground.

This phenomenon was created because of the long range and great height of the trajectory. The muzzle velocity was 3,700 feet per second. The shell's velocity would be diminished by the restraints of gravity to about 2,600 feet per second as it reached its high-point. It would then gather speed as it turned downward toward the target. By the time it reached the ground it would be back close to its original velocity. Its average velocity for the entire flight would be just over 3,000 feet per second, or about three times the speed of sound. At sea level, sound travels about 1,040 feet per second.

Therefore, even though the projectile traveled a longer path than the sound, it would still arrive well ahead of its own sound. Actually the shell would impact the target at about the same time that the sound from the highest point in its trajectory was arriving at the impact area. This gave a false sense of security. From the sound, one was given the impression that the projectile was s till high above the ground when, actually, it was only a few seconds from impact.

I am certain that scientists can explain the sound cut-off phenomenon. My guess is that the shockwave surrounding the projectile canceled out its distant sound waves so that the distant flight sounds arriving at the target area were blocked by this shockwave when the shell was near impact. While I cannot claim to understand it, I can attest to the fact that it occurred.

If the shell was destined for impact a substantial distance beyond or to the left or right of our positions, the sound would fade somewhat, but not stop, and build right back again as it plunged to earth. In this case we could hear the projectile all the way to impact. Being aware of this phenomenon was just another tool for survival and was quickly learned.

I would always tell the new men arriving from the States that in combat you do not live and learn. You learn and live.

Beachhead Spies

At the beginning of the war Italy was an ally of Germany and we were at war with both countries. During the fighting in Sicily, Italy surrendered and supposedly became our ally. But there were many die-hard Fascists in Italy that did not come over to our side.

After the landings at Anzio, civilians were allowed to stay if they chose to. Many stayed.

After a period of time on Anzio Beachhead our intelligence people began to suspect spies in our midst. The Germans knew too much of our plans too soon.

A beachhead-wide search and investigation was launched. The search discovered a two-way radio in the cellar of a civilian occupied farmhouse. The woman's clothesline was the antenna. When she hung her clothes on the line it was the signal for the Germans to get on their frequency. The spies had a message to send. It worked well, because the Germans held all of the high ground and had visual observation of the entire beachhead.

The spies became suspects when it was noticed that the woman often hung out clothes on rainy days.

The spies were caught and dealt with.

After that, all civilians were evacuated whether they wanted to leave or not.

It is strongly believed t hat this spy group was responsible for the details of the first attack on Cisterna being compromised to the Germans. The Germans were aware of the details of that plan, and permitted two Ranger Battalions to pass through their positions at night and then surrounded them. Both battalions were annihilated.

See "A Darby's Ranger, Almost"

Get off the beach.

The Third Division had received much specialized training for amphibious assault landings prior to leaving the US to invade North Africa in November of 1942. Because of this, it was frequently called upon for amphibious operations. The Third Division made a total of four amphibious landings during the war. My battalion, 2nd Battalion, 30th Infantry, made six amphibious landings. In addition to four with the division, it made two more battalion-strength l andings behind the enemy lines in Sicily.

The Third Division always resumed training for amphibious assault landings whenever it was no t committed to active combat. The necessity to get off the beach was constantly drilled into us. During the critique that followed every practice landing, our Battalion Commander, Lt. Col. Lyle W. Bernard, had his own unique way of making this point to us.

His favorite expression was, "horse sh--". He ran the two words together so that they came out as one word, "horsesh--". As a matter of fact, all the troops referred to him as Horsesh-- Bernard. He knew this and never seemed to mind.

He was never satisfied with the speed with which we got off the beach. At the beginning of every critique, he would say, "What I saw out there was a lot of horsesh--. You were too slow getting off the beach. That's pure horsesh--."

You may ask, "What about the enemy machineguns?" I say, "Horsesh--. Get off the beach." "What about the mine fields, sir." I say "Horsesh--. Get off the beach." "But sir, what about the enemy tanks?" I say, "Horsesh--. Get off the beach."

Then he would remind us that the beach was the most vulnerable place to be. All of the enemy weapons had fields of fire covering the beach. Mortars and artillery pieces were always pre-aimed to cover the beach. Enemy planes always flew paralleling and in line with the beach in bombing and strafing runs. Staying on the beach was worse than charging the enemy's positions.

This became painfully true at Normandy on June 6, 1944. Some units sustained unusually high casualties because they were slow getting off the beach.

The last time I saw Col. Bernard over there (I have met him a few times at our reunions since the war.) was on February 19, 1944. He had been severely wounded and was in a large bomb crater giving orders to his field commanders on his radio. A medic was tending his wound and trying to persuade him to allow himself to be evacuated so that he could get better attention.

His reply to the medic was, "Horsesh--. This fight ain't over yet. Horsesh--."

My section continued forward behind the rifle company and I could still hear him using his favorite word until we were out of earshot.

ALTEO

February 19, 1944, our Battalion Commander, Lt. Col. Lyle W. Bernard, was wounded and evacuated. Lt. Col. Woodrow W. Armstrong was given command of the 2nd Battalion.

Soon after taking command, Col. Armstrong decided that the 2nd Battalion needed a battle cry. He wanted something the men could shout as they left their line of departure and charged the enemy positions, something that would inspire comradeship and unity, and that would be intimidating to the enemy (ha ha).

He sent down word that there would be a contest to find a suitable battle cry. He would accept suggestions for one week. Only enlisted men could participate. A panel of two officers and two enlisted men would review all entries and determine a winner.

The winner would receive a thirty-day furlough to the US of A. A large number of men sent in their suggestions. After the end of the one-week entry period, the review panel met and made its selection. They chose, "ALTEO". Pronounced: al as in Albert, tay is in take and o as in oh.

A-All

L-Loyal

T-To

E-Each

O-Other

The driver of the supply jeep that was to deliver supplies to the winner's company that night was instructed to carry the good news to the winner. He was further instructed to bring the winner back to Battalion Headquarters to begin processing of his furlough papers. On that particular night, supplies were being brought up between 0100 and 0200 hours.

Unfortunately, the winner had been on a reconnaissance patrol into enemy territory. The patrol was discovered as it was sneaking back through enemy positions on its return from the mission. (I have to refer to him as the winner because I cannot recall his name.) Enemy machineguns opened fire on the patrol, killing the contest winner. This happened about an hour before the jeep arrived.

Instead of a ride back in the jeep to begin a trip to the States, the winner rode back on the hood of the jeep for burial. He was then turned over to a Grave Regist ration Team, which is the military unit that records the necessary paper work and buries the dead.

The entire battalion was saddened by this tragic event. To my knowledge, the battle cry was seldom, if ever, used in combat. However, in non-combat situations, ALTEO was sometimes used to signify comradeship, and/or support, for a fellow soldier. Even today, at our reunions, ALTEO is used on occasion in the manner stated in the preceding sentence.

One Tiger-Three Shermans

In many instances, Germany's equipment was superior to ours. The best example of that was in their armor (tanks). Their most impressive tank, Mark VI, also known as Tiger, was a monster weighing more than seventy-six tons.

The armor plating in the front was nearly eight inches thick and sloped so that our tank shells just glanced off it. We had nothing that would penetrate the front. Our tanks could only attack it from the sides or rear.

It featured an 88mm cannon. This cannon fired projectiles at 3800 to 4200 feet per second, depending upon the type of ammunition. High explosive shells were in the 3800 f/s range. Armor piercing rounds were in the 4200 f/s range. For a benchmark, consider the fact that this is four times the speed of sound. Not only does the shell arrive ahead of the sound of the cannon, it is ahead of its own sound that it makes traveling through the air. If you hear it, it has passed you.

One morning, on Anzio Beachhead, a German Tiger tank made its presence known. It was hidden somewhere in a stand of trees and brush about one thousand yards to our left front. It was just firing on targets of opportunity. It being well hidden, we were not able to get an exact fix on its position so that we could place heavy artillery on it. Also, it kept changing position. This made it even more difficult to spot.

Finally, about mid-morning three of our General Sherman medium tanks appeared from a group of buildings about 300 yards to the left and rear of my position. These tanks began moving along an unpaved road in the general direction of the Tiger Tank. The land between our tanks and the Tiger was flat farmland. The Germans had to be watching them. I watched in disbelief as they kept rolling along at about half speed. Had they not been warned of the presence of the Tiger?

Suddenly there were two explosions less than a second apart. The first explosion was the Tiger's cannon when it fired. The second explosion was when the shell struck our lead tank. The lead tank stopped dead and the surviving occupants began to exit it.

Immediately, the second tank broke to the right and crossed the shallow roadway ditch and headed into the field. At the same time, the third tank broke to the left and headed for a masonry farmhouse that was very close to the road.

The second tank had barely crossed the ditch when, again, there were two explosions within a second. The second tank was put out of action and the survivors began exiting.

The third tank succeeded in taking cover behind the masonry farmhouse. Our tankers had no intention of taking on the Tiger. They only hoped to survive.

There was a long wait, maybe as much as ten minutes, our tank did not mov e and the Tiger did nothing. Just as I was feeling good that at least one of our tanks was safe, then again, there were two rapid explosions. I looked to the farm house and saw a gray dust cloud rising from the mason ry structure. Black smoke was already coming from our tank and men were scrambling to get out.

The crew of the Tiger had grown tired of waiting for our tank to show itself, and had fired an armor piercing round right through the building and through our Sherman.

After witnessing that episode, I had the greatest respect for our tankers who had to go up against tanks like that.

A Tragic Night

What does it take to survive in combat? Mostly luck! However, experience and composure are great allies on the front line. Some soldiers survive months of combat, while others may only survive a few minutes.

Soldiers with experience react better and make fewer mistakes. Therefore, the longer one survives, the greater is his chance of continued survival. The story related below is a good example of how panic can reduce one's longevity on the front.

Background Info: The Germans used rockets a lot to supplement artillery and mortars. An incoming artillery shell gives you, at most, a one second warning before it hits. A mortar comes in so silently that you get no warning. But a rocket gives you ample warning if you are alert and paying attention, especially at night. In the daytime, if you are looking, you can see the trail of smoke as the rocket rises above the horizon. At night it is much easier to see them because of their fiery tail.

We always had two men assigned the responsibility to watch for rockets and to sound the alarm if they spotted any headed for our positions. It is easy to determine if you are in their line of flight. If the smoke trails or fire trails are vertical, you are in their path. The only unknown is the distance they are set for.

One night in February, 1944, we received two new men as replacements for losses we had taken a day or two before. The new men had no prior combat experience. After interviewing the two replacements, I assigned them to a foxhole that had been occupied by the men they were replacing. In my briefing, I went into great detail about our rocket warning system. I warned them to stay near their foxhole if they chose to get out to stretch. I pointed out that they would have only five to ten seconds to take cover if rockets were on the way.

We received the two men about ten o'clock that night. It was around mid-night when rockets were spotted and the warning was given. Everyone except the two new men took quick refuge in their foxholes. I heard the new men running around shouting to each other in panic. They couldn't find their foxhole in the dark. Unfortunately for them, our positions were the chosen target this time. About six rockets struck our positions in rapid succession and the new men were no longer shouting.

I investigated and found them both dead within a few feet of their foxhole. This was a case where luck was not involved, panic was. Who's to say that these two wouldn't have survived the war if they had only remained calm and reacted intelligently?

I witnessed several other incidences where men became casualties because of their own carelessness or panic. I chose to relate this incident as an example only because these deaths were so clearly avoidable.

Party Line

After about two months, Anzio Beachhead became stalemated. The Germans discovered that they were not going to drive us into the Mediterranean as Hitler had ordered. We did not have the resources to break out.

This began a period of patrol activities to test for weaknesses, and of small-scale attacks to improve positions. Both sides attempted to gain ground without fighting for it by digging new positions at night a few yards in front of present positions.

Finally, our lines, in some places, became so close that we could hear each other milling around or talking at night, even if we spoke in lowered voices. Some of our food rations came in cartons secured with wire bands. The enemy could hear the snap of the wire when it was cut. This told them that we were out of our foxholes distributing supplies. We quickly learned to wrap the wire in cloth and to cut the wire slowly th rough the cloth. This technique would safely muffle the sound.

We had to be extremely careful not to establish predictable schedules and patterns. The enemy would take advantage of our timetable and rake our positions with rockets, artillery, mortars and machineguns when they suspected that we would be out of our holes. Every night, ammunition, food rations and other essentials were brought forward and distributed. It was necessary that these activities take place at widely different times.

For a period of time my section was assigned to positions that were at the most forward position on the beachhead. Our defenses made a very pronounced curvature at this point.

Late one night, my foxhole partner, Chester Borowski, and I heard a strange sound. It gradually grew louder as the source got closer. The sound was a "squeak squawk", "squeak squawk", "squeak squawk". We recognized the sound. It was the sound of a metal spool turning on a heavy metal wire through its center hub. It was someone laying communication wire for telephones. But, was it German or American?

Borowski and I decided to check it out. We put ourselves in the wire layer's path and waited. Just before he reached our ambush point, two riflemen from Company G nabbed him.

It was a German who, because of the nearness of our positions to his, and because of the bend in the front lines, he had unwittingly passed through our defenses and was passing behind us.

His captors ordered him to continue laying the wire and directed him to the Company G command post where the Company Commander hooked on his own phone and listened in on the "party line". We were told that this was good for about a day and a half. It ended when the Germans got wise and cut the line leading to our positions.

My Encounter with a Flare

Anzio Beachhead Mid-April 1944

January through March was a time of much fighting. The Germans were trying to drive us into the Mediterranean Sea. We were fighting to hold onto the ground we had, and to expand and improve our positions as much as possible. By mid-April both sides were ready to call it a stalemate. This began a period of mutual harassment from both sides, consisting of small-scale attacks, artillery and mortar bombardments, and much patrol penetrations into the other's territory.

It was during this stalemate period that I had the following experience: One night, around 1AM, the telephone communication from my machine gun position to my platoon leader's position was lost. I left my position to find the cause and to restore our communication.

It was a very dark but clear night. Every star in the sky was visible and bright. To find the break in the wires I crawled on hands and knees, letting the telephone wires slide through my hand as I moved. As I was searching for the break, I was keenly aware of two possibilities: 1) the wire was cut by an artillery or mortar shell. Or 2) an enemy patrol had cut the wires and was prepared to ambush anyone coming to repair it. With that thought in mind, I proceeded very cautiously.

After proceeding some 50 yards, I came to a clean break in the wires at the edge of a shell crater. After a few minutes of searching in the darkness, I found the other ends of the wires and began spl icing them back together.

In order to see anything at all in the darkness, I had to lie on my back and work above my head. With the stars a s a background, I was able to see just well enough to perform the task.

At one point, while working on the repair, an enemy flare suddenly lit up the entire area where lay. I instantly froze in position, knowing that even the slightest movement would be detected. But, on the other hand, if I did not move, there was a chance I would not be seen.

It was one of their largest flares. It was suspended by a parachute. It was directly above me. The air was cold and still and the flare was not drifting, but coming straight for the spot where I lay.

When it was about twenty feet above the ground, it was evident that, if it did not change course, it would land right on me. A burning flare can burn a hole right through you, so I had to have a plan. If I had to move, I was prepared to roll away from the enemy positions at the last split second. By letting the flare land between us, the enemy would not be able to see through the glare. On the other hand, if it landed behind me, I would be silhouetted by the flare, and they would surely see me.

When it was about five feet above me, and just as I was going to roll away, a gust of air sprang up and moved the flare toward the enemy positions. It landed about three feet from me, and I did not have to move. I remained motionless another thirty seconds while the flared burned itself out.

After recovering from being blinded by the flare, I completed the splice and returned to my position and thanked God for the timely gust of air.

Sacrificial Lambs

After much activity during the first six or seven weeks on Anzio beachhead, the fighting subsided substantially. Both sides became content to just hold the lines where they were. This began a period of mostly patrol activity with an occasional "limited objective" attack.

It was near the beginning of this phase that our machineguns were in positions along a creek bed. The guns were positioned about five feet back from the creek and about 30 yards from each other. The creek provided an obstacle for the enemy in the event of an attack. The down side was that an enemy patrol could use the creek bed to get dangerously close to our positions without being detected.

The creek varied from ten to fifteen feet in width and was six to ten feet deep. Following heavy rains in the nearby mountains, the creek bed would run nearly full. During dry periods it only maintained a foot or two of water that ran in a sub-channel pretty much in the center of the creek bed. It was possible to walk along this creek and avoid the water by staying just outside the sub-channel.

The following incident happened during a period when this creek was at minimum flow.

It was late at night after both sides had settled in for what each hoped would be a quiet night. I was standing watch at one of our machinegun positions when I heard what sounded like rocks falling into the water. I was well aware of our vulnerability to enemy patrols and was immediately alert.

We always kept a good supply of hand grenades beside the machinegun. I picked up one of the grenades in my right hand and inserted a finger from the left hand into the ring that you pull before tossing the grenade.

The first sounds that I heard seemed to be twenty or thirty feet from me. In a few seconds I heard another rock go into the water. I dared not act too quickly. This could very well be one of our patrols returning from a mission.

I gave a challenge and got more rocks in the water in response. I gave a second challenge, louder than the first. The second challenge only produced scuffling of feet and more rocks in the water. The sounds were closer each time. I gave a third challenge with the same results as the first two. By now the sounds were almost directly in front of me.

It was time to act. I pulled the pin on the grenade I was holding and lobbed it into the creek. I followed the first grenade with three or four others as rapidly as I could.

The explosions of my grenades brought the front lines to life. Both sides thought that they were being attacked and opened fire at nothing in particular. This firing spread in both directions from our sector until almost the entire beachhead front was a blaze of tracers. The firing continued for about five minutes and gradually subsided to just an occasional shot, and then finally, all was quite again.

Of course, Troutman, who was asleep in the hole with me, was awake in an instant. He grabbed the machinegun to open fire. But I stopped him and explained what had happened. We both listened for more sounds of activity in the creek, but none came.

Finally, in the gray light of dawn, I ventured out of the hole to see what might be in the creek. I saw five or six hapless sheep, victims of my hand grenades.

These were some of the few sheep remaining from a flock of sheep that were wandering and grazing over the battlefield from the beginning. (See my story entitled "Anzio Shep".)

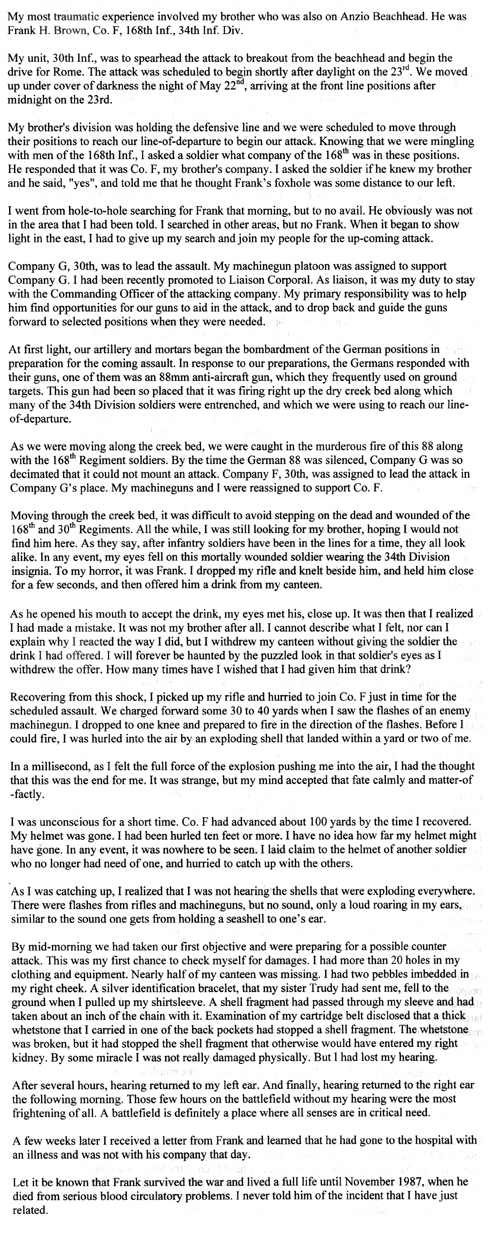

Walla from Walla Walla