Staff Sergeant

Albert S. Brown

Infantrymen

Dull Day

Foreword

Do Something,

Even if it's Wrong

Anzio

Southern France

Colmar Pocket

Germany

Epilogue

Contact Al

dogfacebrownie@gmail.com

![]()

Germany

An anti-tank gun and sentry at guard in Rimschweiller facing the Siegfried Line.

A Close Call in Rimschweiler

Following the successful elimination of the Colmar Pocket in the French zone, the Third Division moved to the vicinity of Nancy, France, for a breather and to receive replacements and to train for the final drive into Germany. After a two-week daily training "breather", the Rock of the Marne saddled up and moved out on March 13, 1945, for the big push to end the war.

At 0100 March 15, 1945, the 3rd Division crossed its line of departure and we were on our way to Germany. The vaunted Ziegfried Line was dead ahead. By March 17, the 3rd Division reached the first fortifications of the Ziegfried Line.

The town of Rimschweiler was jammed right up against the main fortifications. It was a very small, compact town. At the very north end of town was a steep hill that rose a hundred feet or more to its crest. The hillside was covered with many concrete pillboxes surrounded by zig-zag trenches for protection of foot soldiers.

With the town as a barrier, and the steep hill behind, it was not a good location through which to launch an attack. Our main attacks would be at other locations, however; the town had to be cleared of enemy. Our commanders did not want any surprises to our flanks and rear coming out of Rimschweiler.

A combat patrol had to go in and make sure that the town was clear. My section of machineguns was selected to be a part of that patrol. We were briefed for the mission at Battalion Headquarters. Only the lieutenant who was to lead the patrol, and sergeants that would be involved, were at the briefing. Being a staff sergeant, I was present.

We were to move out as soon as it was dark. We were to stop in the southern outskirts of Rimschweiler and wait for an artillery barrage on the northern portion of town to end before proceeding farther. They wanted to give us an advantage in case the town was occupied. We were given the name of a specific street where we were to wait for the artillery to stop firing.

The barrage was to begin at 9PM and was to last for twenty minutes. Only after this twenty-minute barrage were we to advance beyond the street specified. I do not now recall the name of that street, but you can bet the farm that it was burned into my brain that night.

After being satisfied that the town was clear of enemy, we were to set up defenses at the north end of town confronting the Ziegfried defenses. They did not want enemy to slip back into town to disrupt the attacks that were to be launched soon.

Our patrol moved out as soon as it was dark enough. It only took about ten minutes to reach the outskirts of Rimschweiler. My section was following close behind the riflemen. I went up close to each street sign so that I could read it in the dark. I believe that the third street we came to was the street where we were to wait. But the troops in front of us kept going. I checked the time. It was about 8:30PM.

My first impulse was to hurry forward to catch up to the lieutenant and warn him. I then thought that the platoon leader, having radio contact with Battalion Headquarters, had probably received a message that changed the plan. Still, I felt very uneasy as we continued farther and farther into town.

Being a small town, it only took about fifteen minutes to reach the northern limits. As soon as we arrived there, I went to the lieutenant to find out where he wanted our guns placed, and, more importantly, to ask about a change of plan. When I reported to him, he began to tell me where he wanted our guns placed. I interrupted him and asked if he had received a change in orders. He said no. I told him that at 9PM we were going to receive one hell of barrage from our artillery. He didn't know what I was talking about.

I told him that we were to wait at the street that had been specified until the barrage ended. He said that he had heard no such thing and ordered me to get my weapons in position, immediately. I told him that he could have me court-martialed tomorrow, but right then, I was getting my men out of there. That is exactly what I did.

About two minutes after my men and I reached the place where we were to wait, the lieutenant and his platoon came up the street on the double. Even as they joined us, artillery shells began to fly overhead. It was a very intense barrage. There was a continuous screaming of shells as they passed over. They were landing in the area that we had just vacated and in such rapid succession that it was difficult to distinguish one shell burst from another.

After twenty minutes of that, the guns stopped firing, and we moved back into town. The lieutenant thanked me.

For a sequel to the above, see "Stupidity at Rimschweiler".

Stupidity at Rimschweiler

The following is a sequel to "A Close Call in Rimschweiler".

My section of machineguns was part of a combat patrol into Rimschweiler on the night of March 17, 1945. Following a softening up artillery barrage, we went through the town to the northern limits that butted up to the Ziegfried Line.

We had been ordered to set up defensive positions confronting the Ziegfried defenses and wait for further orders.

I positioned each of the guns in basements of adjoining homes so that they could fire through the basement windows in the direction of the Ziegfried defenses. I then strung telephone lines between the two positions so that I would be able to communicate with both guns no matter which house I might be in. After establishing watch schedules for both guns, I lay down for a nap.

The next morning, as soon as it was light enough to see, I moved up from the basement into the house. It was a two-story house, so I went to the second level where I would have a better view of the hill to the north. I wanted to see the type and locations of the fortifications confronting us.

I saw several pillboxes and a lot of zig-zag trenches. My immediate concern was a pillbox no more than a hundred yards away. It was so located th at its field of fire was right up the space between the houses that our guns were in. The distance between the buildings was at least twenty feet. That meant it would be suicide for me to try to move from one gun to the other. It was important for me to be able be at either gun. I needed a safer route.

I went downstairs to the front door. I liked what I saw. The houses on the other side of the street were staggered from the houses on my side. This meant that I could cross the street with my house protecting me from the enemy. I could then pass behind the house across the street and approach the house where the other gun was located, again, without exposure to enemy fire.

I followed this route and entered the other house via the front door and proceeded to the basement. There I warned the men of the menacing pillbox and instructed everyone, that, if they wanted to visit anyone at the other gun position, they should take the route behind the house across the street. Under no circumstances was anyone to be in the space between the two houses separating our positions.

Returning to the other gun, I gave everyone there the same instructions. I then went back to the second story to study the defenses against us. After about thirty minutes, I heard machinegun fire coming from the hillside and I saw gun flashes coming from the pillbox directly in front of us.

I hurried to the basement to see what was going on. I was told that one of the new men (I do not recall his name.) who had joined us as a replacement while we were in Nancy, had gone out a side door to go to the other gun to visit a friend he had come from the States with. He had been hit, but was able to make it to the front of the other house, out of the enemy's line of fire.

I talked to my people at the other gun position by phone and asked what they knew about his condition. They reported that the man was badly wounded and that the rifle platoon's medic was tending to him. They managed to evacuate him a little while later. I do not know whether he lived or died.

That night, March 18, we were pulled out of Rimschweiler to join our battalion in the attacks against the Ziegfried Line beginning March 19.

Beer in Zweibrucken

The ruins of Zweibrucken.

My twenty-first birthday, March 20, 1945, all three regiments of the Third Division, in simultaneous attacks, breached the Ziegfried Line and captured its first German city, Zweibrucken.

In Germany, all civilians were to be considered potential enemies. Homes were to be searched for weapons and, of course, cleared of enemy soldiers. In the process of clearing homes in a residential neighborhood of Zweibrucken I, and two of my men, were checking one of the homes. On the dining room table was a pitcher of beer surrounded by several glasses just waiting to be filled. When the men saw the beer, one of them said, "Oh boy, beer." I replied, "Yes, beer waiting to kill you. Dump it out and follow me to the next house."

Without looking back, I went through the kitchen and out the back door to the next house. The two men had not caught up with me by the time I had checked the next house. I was a little concerned. I encountered other men from my section who were checking other houses in the neighborhood. I sent one of them back to find out what was delaying the men who had been with me.

About twenty minutes later, the man who went to check on the others caught up with me. He reported that he had found them rolling around on the floor in pain. He reported that he had located a man with a radio and had called for the medics to come for them. He also said that the pitcher of beer was half empty and that there were two glasses on the table with just a little beer left in them.

Those men were never returned to unit. I never knew whether they lived or died. I just chalked them up as two casualties due to insubordination and stupidity.

Anxious Moments in a Barn

One night, somewhere in Germany, my machinegun section was following close behind the rifle company we were supporting as it advanced through a small farming village. The village had been subjected to artillery fire ahead of our advance. Many houses were ablaze. The flames stood out in contrast to the inky black night. A light rain from low hanging clouds added to our discomfort.

The riflemen in front of us were not in contact with the enemy. They were advancing cautiously in anticipation of ambush from rear guard units. From time to time forward movement would stop as point men (scouts) would see or hear something suspicious.

It was during one of these pauses that I happened to be beside a large barn. A burning building behind me was silhouetting me. Not wanting to be a tempting target, and also to get a brief respite from the rain, I stepped into the barn. The inside of the barn was even darker than outside.

I stood just a few feet inside, with the door ajar so that I would know when the troops began to move. I had been there for less than a minute when I thought I heard someone move inside the barn. I listened intently. In a few seconds I heard it again. It was a very faint noise like feet moving in the straw on the floor.

I thought of how vulnerable I was in the open doorway. Anyone inside would surely see me. Was it a patriotic citizen with a pitchfork, or possibly a German soldier who had fallen asleep and had failed to wake up when his comrades left? It was very common to encounter enemy similarly left behind. There was also the possibility that one of our men had decided to "take five" and had just awakened.

I leveled my rifle in the direction of the sound and gave a challenge. There was no response except that, whoever it was, began moving faster toward me. I gave a second challenge and got the same result.

When I gave my third challenge, it was in a much louder voice and I promised to shoot. Again there was no verbal response, only faster movement toward me. By this time whoever it was, was within pitchfork range and I tightened my finger on the trigger. An instant before my rifle would have fired, I got a response. The farmer's cow said, "Mooooooo."

Bad Decision Leads to Mini Bridgehead Across Rhine

Engineers work on a pontoon bridge across the Rhine River near Worms, Germany after initial Third Division assault troops secured the far bank.

I joined the Third Division on Thanksgiving Day, 1943, and was assigned to First Section, First Platoon, Company H, Thirtieth Infantry Regiment. I served in the First Platoon, Company H, to the end of the war.

I arrived as a private, and by the time we were ready to cross the Rhine River the night of March 26-27, 1945, I was a Staff Sergeant and Section Leader of the First Section, First Platoon, Company H. Our primary weapons were two water cooled, 30 caliber, heavy machine guns.

Under the cover of darkness on the night of March 26th, we moved up to the west bank of the Rhine River to wait for the Engineers to bring up the boats that were to transport us to the east bank of the Rhine where the Germans awaited and expected us.

The boats were brought up some time after mid-night. After heavy artillery bombardment of the German positions, we were ordered to load into the boats and proceed to the east bank.

I helped the men load themselves and their equipment into one of the boats and took up a position in the bow. The Engineers provided a coxswain (a Corporal) to operate the outboard motor, which I think was a twenty-five horsepower Johnson.

Our coxswain had a bit of difficulty getting the motor to start. But after a dozen pulls on the starter rope, and a few choice expletives, the motor started, hesitantly for a while, and then it smoothed out to full throttle and we were on our way. However, when we were maybe 100 yards out, the motor quit abruptly.

The coxswain began trying to restart the motor. After several fruitless pulls on the starter rope, I ordered everyone to get their shovels out and to begin paddling to the east bank.

The motor never restarted, and by the time we reached the east bank, the fast flowing Rhine River had swept us maybe a half-mile north of the scheduled landing site. I suddenly realized that I had not made the best decision when I had us paddle to the east bank. At the time I made the decision, I expected the motor would restart, and with its power, we could buck the strong current and land with the others.

Having landed so far from the main body, I fully expected that we would be annihilated or taken prisoners. By good fortune we had landed at a sheltered spot where the bank was not too high. We tied the boat off to some heavy brush and unloaded without a sound.

Leaving the men and equipment by the boat, I crawled over the bank and explored a fan-shaped area to about fifty yards out. Not encountering the enemy, I returned to the men.

While we were still paddling across the river, the main body was already engaged with the enemy to the south of us. We could hear the shooting and see tracers flying everywhere. Apparently, the fighting to the south had drawn the enemy troops from our landing site. Whatever the reason, I was thankful that we were not fired upon. However, I really did not expect to make our way through the two firing lines to join our troops without a fight.

The men, being burdened by the heavy equipment, would not be able to respond quickly if fired upon. It was necessary for me to be the point man. I would move ahead about fifty yards at a time, return to my unit, and bring the men to the limit of the area I had just explored. By repeating this sequence, we began moving toward the main body, where by now, the fighting was really picking up.

I kept as close to the river bank as I could. If we were fired upon, the bank would provide a protective palisade to fight from.

Another big concern was time. It would be daylight soon, and it would be impossible to move this group of men and equipment in full daylight without detection. I moved as fast as I dared, but avoiding detection required patience and caution.

I was able to distinguish enemy machinegun positions from ours. The Germans' tracers were white, whereas ours were pink. Of course, not all guns fired tracers, but those that did, provided me a pretty good idea where the main firing lines were and the locations of the strong points. Also, it was easy to tell the difference between their machineguns and ours from the sound.

Finally, when we were maybe 200 yards behind the enemy's main defense perimeter, I observed white tracers coming from two positions very near the river. It was obvious that we would have to break away from the comfort of the riverbank. I chose an area that seemed to have the widest space between firing positions and began moving toward it. When I had gotten the men to within about fifty yards of the Germans' firing line, I told the men to stay put until I came for them. Even if we succeeded in slipping between the enemy strong points, we would likely be cut down by our own troops, who would logically mistake us for attacking Germans.

I found a shallow gully between two firing positions and worked my way past the Germans a few feet at a time. Divine Providence was with me that morning. I reached our positions unscathed. I reported that I had sixteen men and two machine-guns behind the enemy positions and that I was going back for them. I asked that they keep the enemy busy, but not to fire in the direction we would be coming from.

It was truly a miracle. We succeeded in getting through to our side without a scratch, and about 30 minutes before daylight.

I have often wondered what happened to that Engineer Corporal that I left stranded on the Germans' side of the river. I hope that he did not fall into their hands.

He probably wanted to get his hands on the stupid sergeant who paddled across the Rhine when he could have returned to the west bank and taken another boat.

Nurnberg Medic

Albert S. Brown — Somewhere in Germany, April 1945.

Nurnberg was declared by Adolph Hitler to be the most German of all German cities. It was the primary source of his political support that propelled him to power. In the center of Nurnberg was the infamous Adolph Hitler Platz where most of his political tirades were carried out in front of many thousand cheering, fanatical followers.

Many Nurnberg citizens joined their soldiers in the fighting for Nurnberg, vowing to hold the city past Hitler's birthday as a birthday gift to him. The battle for Nurnberg began April 17, 1945. It ended on Hitler's birthday, April 20, 1945, when the Adolph Hitler Platz fell to the 2nd Battalion, 30th Infantry.

On April 21, 1945, the Third Division held a special flag raising ceremony in Adolph Hitler Platz, renaming it "Eiserner Michael Platz" (Iron Mike Square) in honor of the 3rd Division's Commanding General, Major General John W. O'Daniel, who was known to his troops as "Iron Mike." When the ceremony was over, a huge American flag hung atop the Zeppelinfeld in front of the Hakenkreuz (Swastika) totally eclipsing it.

A podium was erected for Third Division pomp and circumstance on April 21, 1945 in the former Adolf Hitler Platz in Nurnberg.

General Patton, commander of the Third Army, sent Iron Mike a message asking him to preserve the Hakenkreuz, that he, Patton, wanted to have it removed and added to his personal collection of war memorabilia. The next day, Iron Mike had a demolition crew blast it into very small pieces.

The remants of the Hakenkruez litter the field in front of Nurnberg's Zeppelinfeld stadium. The day before it was destroyed, five Third Division soldiers were honored with the Medal of Honor on the podium under the U.S. flag-draped swastika.

The above victory did not come without its price. It came after four days of hard continuous fighting during which an incident involving a frontline medic occurred. It is that incident that I want to be the real focus of this story.

The inner city was almost totally destroyed by bombs, tanks and artillery. The enemy made good use of basements and piles of rubble to delay our advance. Snipers were everywhere and difficult to locate in the rubble.

American tanks enter the destroyed city of Nurnberg.

Just before dusk of the third day, we received fire from a sniper hidden in the rubble. The lieutenant in command ordered everyone to take cover and dispatched four men to out-flank the sniper and eliminate him.

While we were waiting in an area that was out of the sniper's field of fire, I struck up a conversation with the platoon medic. He was very young, probably eighteen. His uniform was much cleaner than most of the other soldiers, and I suspected that he had not been in the frontlines very long. He told me that he had completed his training as a frontline medic a few weeks before, and had just arrived from the States and was assigned to this platoon two days earlier. This was his first battle.

As we talked, we noticed one of our soldiers across the clearing that was being covered by the sniper. The soldier looked our way and went into a crouch. It was obvious that he intended to join us. Several of us motioned to him to stay put and shouted "SNIPER" as loud as we could.

The soldier did not heed our warning and made a dash across the open area that was about fifty yards wide. When the soldier had made it about halfway across the clearing without being fired at, I thought that maybe the sniper had left. Then, with only ten yards to go, a shot rang out, I saw the soldier's body flinch as the bullet struck him. He continued to run and fell into our protected space.

The young medic was on him immediately looking for his wound. I watched while the wound was located. The bullet had passed cleanly through the soldier's chest, from side to side, leaving two holes that were bleeding profusely. The wounded man was alive and trying to talk.

The medic rolled the man face down, and got on his knees straddling him. Then, with thick medical pads in each hand, he reached around his patient and began pressing the pads against both wounds in an effort to slow the bleeding.

Having heard the shot, the lieutenant in command came to investigate. He saw the wounded man face down with the medic over him. The lieutenant ordered the medic to get off the man and to roll him onto his back. Without removing his hands from under the man, the medic attempted to explain to the lieutenant what he was doing. The lieutenant would not listen and again ordered that the man be placed on his back. Still, the medic resisted and tried to explain to the officer that it would be wrong to do so.

The officer shouted at the medic, "Soldier, this is a direct order. Roll that man over, now." The medic reluctantly moved to one side of the soldier and rolled him over as ordered.

With the soldier on his back, the medic got two fresh pads and began holding them on the wounds. Within a minute, as all that were near looked on, the man drew his last breath and closed his eyes. The officer walked away.

The medic checked the soldier for a pulse to confirm that he was gone. He got up with moist eyes and said to me, "Sarge, I killed him." I said, "No, the war killed him. You did everything you could to save him." He then explained that he had the man face down so that the blood would drain away from the lungs and that when he rolled him onto his back, the lungs filled with blood, drowning him.

I remember thinking, "Why isn't he blaming the lieutenant?" I wanted to, but decided against it. I did tell him that he did not have to follow the lieutenant's order in that situation. The lieutenant was acting outside of his authority. That he, the medic, was the one trained in first aid, not the lieutenant.

Nurnberg was the last big battle of the war that ended May 8, 1945, eighteen days later. There were a few more skirmishes, and only a few more casualties. It is a good possibility that the sniper victim was that medic's only patient in the war. I have often thought of him and wondered if he returned home feeling like a total failure.

Our frontline medics have never been given much, if any, publicity since the war. The heroics of those who got medals for killing people get a lot of publicity. We hear very little about our medics for saving people.

They did their jobs under the most difficult conditions. Often they performed first aid on the wounded in exposed places while combat troops could find cover in shell holes, ditches and other depressions. The medic did his work wherever the wounded man happened to fall.

We always took special care of our medic. He was like a security blanket. There were many times that we would be without a medic for a few days while waiting for a replacement for one that had been killed or wounded. Moving forward without a medic gave me a naked feeling, like being without my helmet.

During the war, the War Department decided that combat infantry soldiers should be given extra hazardous duty pay and recognition. A Combat Infantryman's Badge was developed. We were issued the badges and began receiving a monthly bonus of ten dollars. The frontline medics were not authorized to receive the badges or the ten-dollar bonus because they did not fight. Our hero, Bill Mauldin did a cartoon in protest of that idiotic decision.

Nein Heil

After the war ended, my regiment was assigned occupation duty in and around Kassell, Germany. There was a German citizen who worked with us in our search for war criminals. He was very helpful to us in identifying and locating German war criminals. This man's right arm hung to his side like the arm on a rag doll, and it was just as useless.

He was a very patriotic German who did not agree with Hitler and the Nazi Party. He chose not to abide by the political "Heil Hitler" requirements.

One day, as part of a huge throng gathered to hear one of Hitler's tirades, he would not do the "Heil Hitler" thing along with the vast majority. His failure was observed by Gestapo agents who watched for "enemies" of the state. He was dragged from the plaza into a building where his right arm was secured to a table and the Gestapo agents repeatedly smashed his arm with their rifle butts until the entire arm and hand were like jelly. He was then released and told that if he would not use his arm and hand to salute their Fuehrer, he would never use it for anything else.

Final Thoughts and Memories

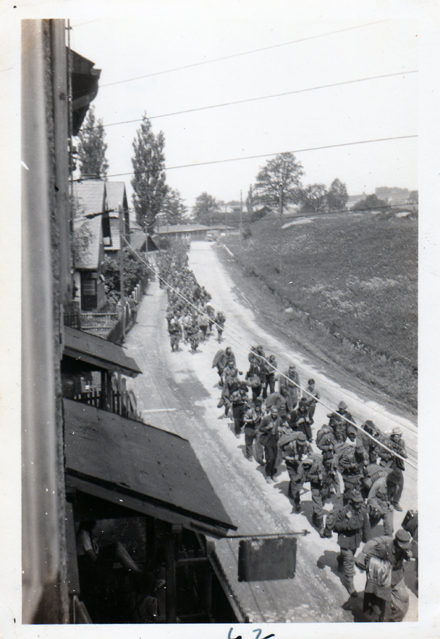

Salzburg, Austria, May 7, 1945, disarmed German soldiers as seen from the second story window of a Salzburg residence.(photos taken by S/Sgt. A.S. Brown as he observed the procession with mixed emotions.)

The place was Salzburg, Austria. The date was May 7, 1945, one day before the official, unconditional, German surrender in WWII on May 8th. The 30th Infantry Regiment had just liberated the city of Salzburg on May 5th after 31 months and ten campaigns of hard fighting that began November 8, 1942, with assault landings on North Africa. I had fought in the final seven of those ten campaigns and was watching from a second story window of a Salzburg residence as a column of unarmed German soldiers, three abreast, marched past in the street below.

As I watched this column move past, it gradually seeped into my mind that the war was over and that I was alive. For many months my future had been limited to one minute at a time, from one shell burst to the next, from one machinegun burst to the next, and now it was dawning on me that my future had the potential of lasting a normal life span. It was like waking from a dream and wondering whether the dream you had just experienced was real or just a dream.

As the reality took over my thinking, I experienced a euphoria that I had never experienced before or since. However, as this joy was reaching a peak, I began thinking of comrades left behind in cemeteries across Africa and Europe and my emotions did a 180 degree reversal until I reached a state of sadness never before experienced. I was no longer that innocent high school kid who went to war on March 12, 1943. The war had changed who I was and now am.

As I continued watching these defeated soldiers pass beneath me, I began to feel sorry for them. What must they be feeling? What would be their future in their destroyed country? Then I remembered that my mother had come from Germany and had left six brothers behind. I began to wonder if any of these men were my relatives. I wondered if somewhere among the older soldiers was one of my uncles and if among the younger ones was maybe a cousin.

Then I wondered if I had possibly, somewhere along the way, killed or seriously wounded a cousin or an uncle. Had any of these relatives nearly killed me?

With all of these thoughts racing through my mind, I fully realized the madness that war really is. And, I recall a feeling of great satisfaction coming over me because we had just concluded the war to end all wars. That was the promise the politicians had made to us. Wow, how wonderful the future was going to be. Think of it, no more of this madness. How na´ve that 21 year old was.

False Alarm

WWII had ended on May 8, 1945. A few days later, after we had finally convinced ourselves that we were not dreaming, that the war was really over, and we had survived, it was a time to relax. We were not concerned about tomorrow. Whatever tomorrow brought, it would not be more combat. We could handle it. Bring it on!

Then, whamo! The order came down for the 15th and 30th Regiments to move out with full battle gear. Intelligence reported that there were an unknown number of SS troops holding out in the mountains near Hitler's infamous Eagle's Nest. The word was that they were led by the notorious SS General Heinrich Himmler, and that they were prepared to fight to the last man rather than surrender.

What a bummer! Our sense of safety was abruptly taken away. Here we go again. What a shock this was to our psyche.

So off we go into the mountains searching for an enemy we really didn't want to find. Over a period of four or five days we swept through the area where the SS were supposed to be. No enemy troops were encountered. Finally it was decided that our commanders had received bad intelligence and we moved back to Salzburg where we awaited orders for occupation duty.

For once, bad intelligence was good. However, this served to remind us that we were not civilians yet, but soldiers who could be ordered into danger at any time.

Why Not Me?

On my trip to hell and back,

I learned that bullets, inches from your ear, do not whine, they crack!

Bombs and shells have launched me bodily.

How many times? I'm not sure, but more than three.

I have walked with comrades 'midst swarms of tracers in the night.

And once, in broad daylight, I even saw an angry shell in flight.

Again and again we charged the enemy lines.

We moved against bullets, shells and mines.

We moved together, my comrades and I.

How was it determined who should live and who should die?

For years I have pondered this mystery.

Why was it them? Why not me?

Albert S. Brown |

Infantrymen |

Dull Day |

Foreword |

Do Something, ...

Anzio |

Southern France |

Colmar |

Germany |

Epilogue

Reprinted by permission. |