Staff Sergeant

Charles O.

Beardslee

Prelude

Signing Up

Africa

Sicily

Italy

Anzio

Southern France

Vosges

Colmar Pocket

Wounded

Going Home

![]()

March 1945 : Twist of Fate

With gun emplaced what do you do but wait.

In the second week of March1945 my platoon left Neuf Brisach with a move to Nancy, France where the division received replacements and did a lot of training.

I ran a .50 caliber machinegun school. I showed the men in the rifle companies how to load, fire and aim properly. I was finally promoted to staff sergeant and that helped my morale a little.

One day I was reading the company bulletin board and found a notice that said any of the first three grades of enlisted man (that meant staff, tech, or master sergeant) with a Purple Heart award or better who could pass the army intelligence and aptitude test at 110 or above could sign up for Officers Candidate School in Paris.

This sounded like the greatest news I had heard in a long time. I was dreaming of 90 days in Paris and by the time I had completed the school the war would be over. The men could smell the end of the war in the air. The Remagen Bridge had been taken only five days earlier. Two full divisions across were across the Rhine, the biggest obstacle to the American Army sweeping across Germany.

I went to the company commander, Captain Davis and he informed me that I didn't have to go to O.C.S. to become an officer he would take me to regimental headquarters and they would make an officer out of me within the hour and I could command a platoon in B Company. Wow, he scared the hell out of me and all I wanted was 90 days in the safety of Paris to give my nerves a chance to heal.

Charles with Swastika.

Captain Davis told me if I went to the O.C.S. that I would have to stay in the service and the army of occupation for an additional year. I said that it would be fine if I could break into the officer ranks by going to school. I said I really wanted it.

I didn't tell him that I wanted it because I felt had to get off the front line. Battle fatigue was eating into the core of my body and I needed a rest. I didn't know how long it would take before they sent me to Paris. Maybe it just wouldn't happen at all.

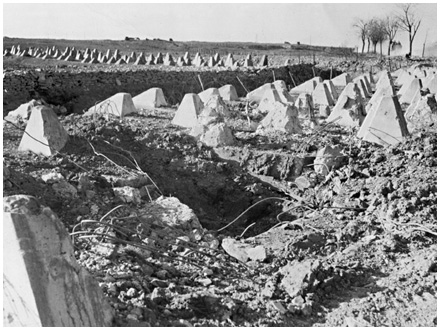

The Siegfried Line

Tank traps on the Siegfried line.

It was around March 12, 1945 that my battalion was loaded into trucks and driven 50 miles north and to the east of Nancy. We spent the night waiting for orders to get back to the meat grinder. We finally got orders to attack on March 14.

I will never forget that night.

The battalion was assembled in the darkness of a muddy farmyard. C Company was chosen to move out first. As the men got beyond the farm's coral they ran into the worst minefield I had ever seen. We had 19 men killed or wounded trying to find a way through.

The engineers came up with mine detectors. It took two hours before we could get on with the attack.

I was outside the minefield so I looked around in the dark trying to find a place to lie down and catch a few winks. I found a jeep with a trailer so I thought maybe I could lie down in the trailer. As I was feeling around in the dark I found a half dozen or so dead soldiers.

I never found a spot to sleep so I spent the two hours standing around in three inches of barn slop.

The engineers marked both sides of the trail through the minefield with reflective white tape. The trail was about 18 inches wide and it had to be followed it in the dark.

The anti-tank platoon was attached to B Company and we followed them. It was still very dark as we moved across a large field and up a ridge and the Krauts must have heard us coming. They threw up flares that lit up the whole area and there we were standing like a row of fence posts along the top of the ridge.

As we moved along I kept looking to the front for signs of enemy action when I saw the flash of a large bore gun. I automatically hit the ground, something I had learned in my years of combat. The shell went right over my back and landed and exploded only eight feet on the other side of me. I heard someone in the dark say, "Beardslee just got it." I replied, "To hell he did, now let's get off this God-damn ridge."

As soon as we got off the ridge the Germans quit shooting flares. Our progression speeded up until B Company approached a village and ran into some machinegun fire.

A Lot of Guts

Morning was coming on. There was a slight fog but I could see what was happening to our troops 200 yards ahead.

I saw the Kraut machineguns hit two men. I ordered my squad forward on the double to where our bazookas could reach the machineguns. The bazooka teams took out all three machineguns with two rounds each. Then Baker Company moved on.

Later I found out that the two men I saw killed by the machineguns were both lieutenants. I latter learned that every officer in B Company was killed by noon that day. If I had taken the battlefield commission I was offered only a few days earlier I would have advanced to company commander.

The objective was to push through the Siegfried Line. The line had row upon row of trenches and tiger teeth anti-tank defenses. There were concrete pillboxes with interlocking fire, barbed wire and the defenses were spread out two miles deep.

It was a good defensive line but ol' Hitler was running out of men to defend it. Even with their best soldiers we could have gotten through. You can't imagine what 1,000 bombers could do to that impenetrable line. I was convinced then and always have been since that nothing could have stopped us at that time. Not even today. The American G.I. is one of the best soldiers in the world.

Methods for attacking pillboxes had been developed that worked. The weak part of a pillbox was the opening. We used a lot of smoke in front of the opening so the enemy could not see as we would approach close enough to use a flamethrower or a pole charge in the opening.

It took one hell of a lot of guts. The men that did this or were involved in any way should all have received at least a Silver Star.

The pillboxes that had larger guns meant we had to call in the air corps with bombs and napalm. Tanks were sometimes effective if the terrain was favorable. I remember one time a bulldozer was used to push dirt to close the aperture then welders welded the steel doors closed in the rear so nobody could get out.

Our first try to punch a hole through the enemy line met with much resistance so we pulled out and went to an area where the ground was more favorable. We moved into a slaughterhouse as mortar rounds crashed all around. The rich soil was churned into fountains of dirt. Machinegun bullets cracked all around.

Things got confusing as men were hit and those that were left continued to advance into the Hell of the Siegfried Line.

The enemy had a mortar that fired a 1,000-pound shell. When it hit the earth it blew a hole ten feet deep. It gave me a bad case of nerves. The shells came over about every 20 minutes.

They were meant to harass because they didn't have a real target. There was nothing we could do to stop it.

My squad had a roadblock on a road that went right through the Siegfried Line. The rifle companies were about 200 yards forward.

For the time being things were quiet, when all of a sudden I heard the most powerful noise coming out of the sky. I looked to see my first jet airplane. It was German and I had never seen an airplane go that fast before. Anti-aircraft fire never came close. The shells burst five miles behind the airplane as it sped away.

This event didn't do my morale well to know that the Huns had a better airplane than ours. We were occupying a small house along the side of a rural road that ran directly through the Siegfried Line. We had our roadblock established at this point. From the house we could see right down the road.

Since it was a dirt road we dug holes in the road about 50 yards ahead of the house and placed anti-tank mines in the holes camouflaging them as best as we could. All the bazooka teams were ready with bazookas loaded and ready to fire. Our .50 caliber machinegun was dug in and the first round rested in the chamber ready for any enemy infantry attacking through the surrounding fields. This was the best we could do until our anti-tank gun arrived. That wouldn't be for a few hours and I always felt weak with out it.

A Million Dollar Wound

About 0900 in the morning a young soldier from one of the line companies came to the house looking for a medic because he had been shot in the leg. It was only a flesh wound in the calf of his leg and of course it was very sore to walk on.

We got him comfortable and gave him a hot cup of coffee and tried to get him to eat something. I called the medics to come up with a jeep and get him evacuated. The medics told me it would be a two to three hour wait since he had taken sulfa pills and had what was referred to as a "million-dollar wound".

(ed note: million-dollar wound: military slang referring a combat wound that is will get a soldier off the front but is not fatal or crippling.)

The wounded soldier sat on the floor in the corner of the room and we didn't pay much attention to him. We thought he was trying to sleep.

An hour later one of the men in my squad went to see if the wounded soldier needed anything and he was dead. Shock apparently took him. Everyone was blaming themselves for letting it happen.

Then it Happened

Around noon we moved into another room of the house and sat on the floor to open our noon K Ration. Someone was heating a cup of coffee on our single burner Coleman gas stove. I was sitting in a window opening. The window glass had probably been broken by airplanes shooting up the roads earlier. Then it happened.

There was a blinding flash and I came to lying on the ground. I had been blown out of the window and landed on my head about ten feet below. There was a good crack on my head and in fact I had suffered a skull fracture. I was confused about what had happened. I had to claw my way up the hill and back into the house.

There was only one person alive. He was lying face down on the floor with his head turned so he could see me. He said, "Help me, help me&qout;. I couldn't hear anything. I was only seeing his lips move. I looked at him to see if there was anything I could do.

There was nothing left of him from his waste down and he died a second later. I was there in the blood and gore trying to think what I should do. I left and went to the rear and found Sergeant Leaser. I had no helmet, no rifle, I was bleeding around my face from small pieces of sand blown into my skin. I was a mess and certainly didn't look like soldier.

Hospital

Sergeant Leaser listened to my story. When I finished I completely broke down and started to sob uncontrollably. Sergeant Leaser took me to the aid station and I got a shot of morphine was shipped by ambulance to a hospital. In 15 minutes the morphine calmed me and within two hours I was at a hospital.

I don't remember where it was I do remember that the beds were just fold-up army cots with no sheets. After two nights and three shots of morphine I was shipped to a much larger hospital in Nancy, France. Clean sheets, flush toilets, showers and best of all the nurses wore dresses.

The doctors dug the pieces of sand out of my skin after I was cleaned up. I found myself wanting to sleep much of the time probably from the conk on the head and just complete nervous exhaustion.

Charles O.

Beardslee | Prelude | Signing Up | Africa | Sicily | Italy | Anzio |

Southern France | Vosges | Colmar | Wounded | Going Home

Memoir appears by permission |