Biography of RussCloer

Capt., I & R Platoon Leader, 7th Inf.,3rd Inf. Div., VI Corp., 7th Army, USArmy

Table of Contents of Russ Cloer's WorldWar Two Story

I was born in Jersey City, N. J. on January 4, 1921. Allfour of my grandparents were born in Germany and emigrated to the U. S. inthe late 1800's. My parents were both born in this country. They lived inthe Jersey City - Hoboken area, popular with other German immigrant families.My father was the youngest of five children, my mother, one of six. Neitherof my parents was educated beyond the 6th or 8th grade because they had togo to work at an early age to help support their parents and siblings. Myfather became a toolmaker, my mother a seamstress and after marriage, ahomemaker. My paternal grandfather was a carpenter and lived to the age of91. My maternal grandfather was a construction worker and he died in hislate 30's when he fell from the roof of a building. There was no Social Securityin those days, no unemployment insurance, no workman's compensation, no childlabor laws, and in immigrant families, no relatives on whom to lean forsupport.

My earliest recollections go back to my first 4 years.We lived in a 3rd floor "railroad" type walk-up apartment in a wood frameapartment building in Jersey City, N. J. And we shared a bathroom with theadjacent apartment on the same floor. We had no telephone, no radio and nocar. Nor did many of our neighbors, in those early 1920's. But my fatherhad a red Indian motorcycle with sidecar that he kept in a nearby rentedgarage. On summer Sundays, my mother, my younger sister and I would pileinto the sidecar and we would go for a ride, usually to visit one of my manyaunts and uncles, all of whom lived within easy driving distance. In winter,my father stored the engine and transmission under his bed, when he wasn'tworking on it on the kitchen table.

When I was four years old, my parents bought a very old2 bedroom wood frame house on a 50 by 100 foot lot in Roselle Park, N. J.We thought we were living in the country! We were happy there, despite theconstant home maintenance required. The school system was good, the neighborswere amenable, stores were just around the corner and the railroad, whichtook my father to work, was only a 3 or 4 block walk. (Or run, if he waslate, which was more often than not.)

I entered kindergarten at age 5, and since the cut-offdate was January 1 and my birthday was January 4, I was the oldest kid inmy class all through school. This had certain advantages for a boy! The only‘disadvantage' was that I would graduate from high school one year later.(And as it turned out, enter the Army one year later!)

My childhood was a happy time, even though I didn't havemany of the things my friends had. Despite growing up during the GreatDepression, I don't remember ever going hungry nor lacking suitable clothesfor school. Of course Christmas and Birthday gifts were pretty sparse andmost of my few toys (precious to me) were home made or second hand. And Iwasn't alone. That was the norm during the Depression. (Home-made scootersmade from a discarded roller skate, a 2 x 4 and a discarded orange crate;home-made wooden stilts; sling shots from slices of an old inner tube anda Y shaped tree branch; rubber band guns from slices of the same inner tubeand a piece of wood; a bag of scratched marbles and a "nickel rocket" baseballthat we would wrap with friction tape when the seams broke.

In 1933, my father was laid off and there was no longera pay envelope on Fridays. Our mortgage payments on the house were $22 amonth and my parents didn't have it. We were in danger of losing our house,our place to live. But the mortgage holder couldn't resell the house in thoseDepression days, so he agreed to accept interest only, no payment of principal,"until times got better." The payments became $11 a month and we hung on.I distinctly remember being entrusted to take the $11 in cash to the bankonce a month. Of course we had no checking account. I remember my fatherleaving the house every morning at the same time, to look for work. And returningin late afternoon with a haggard look. Machine shops at that time would hireworkers only when they got a contract, and when the deliveries were completed,they would lay off the workers. Somehow we struggled through until war cloudsloomed and the economy began to recover in 1939.

Also in 1933, a new Boy Scout Troop was formed in our smalltown. I had just reached my 12th birthday and was invited to join. But joiningrequired that I have a Boy Scout uniform. The uniform cost $7 and my parentsdidn't have it. (Plus $3 for the hat which was optional. I knew only 3 boyswho had a hat!) But somehow the uniform, (less hat,) appeared and I becamea Boy Scout. The troop was sponsored by the local Rotary Club, and I suspectthey had a hand in making the uniform available. I was active in Boy Scoutsfor 5 years and it was one of the greatest experiences of my life! I knowof no better way to instill a set of worthy values in our youth. "On my honor,I will do my best to do my duty to God and my country and to obey the ScoutLaw. To keep myself physically strong, mentally awake and morally straight.""A scout is trustworthy, loyal, helpful, friendly, courteous, kind, thrifty,brave, clean and reverent."

And when I grew old enough to notice girls, I had to lookno further than the house next door. Living there was Beverly, the girl ofmy dreams who is now my wife of 59 years!

I always did well in school, making the Honor Roll everyyear, but in those times there was no thought of going to college. Few peoplehad the money. I remember when I entered High School, (9th grade) in 1935,having to choose between the "College Course", the "General Course," or the"Commercial Course." Like 80% of my classmates, I elected the "General Course."For electives, I chose what I thought would help me get a job when I graduated:Bookkeeping, Typing, Shop, Junior Business Training, etc. My parents didn'thave sufficient education to give me much guidance and no one else offeredto.

But a wonderful thing happened to me near the end of my secondyear! My History teacher told me she had been looking at my grades and wonderedwhy I was not taking the "College Course." I told her we couldn't affordcollege. Actually, I had never given it any serious thought for that reason.She said she thought she could get me a scholarship when the time came andshe would help by guiding me through the application procedures. I didn'teven know what a "scholarship" was at that time! She arranged for me to taketwo years of a language and two years of algebra as electives in my lasttwo years to meet minimum college entrance requirements. I am eternally gratefulto that lady.

In my third year of high school, my algebra teacher, whowas also coach of the track team, suggested I "come out" for track." "You'retall and skinny," he said, "just the right build for the high jump." I tookhis advice and won the high jump in 10 out of 10 dual meets that season.I was elected captain of the track team in my senior year, won the Statehigh jump championship and set a new State record for the event. I thinkthat too, may have had a bearing on the scholarship award.

I graduated from high school in 1939 as valedictorian ofmy class of 128 graduates. I applied for academic scholarships at two colleges,with help from my teacher "angel", and was offered a full tuition scholarshipat both. I chose Rutgers University.

In high school, competence in sports was the key to popularity.At my 50th High School Reunion, everybody remembered my track record. Onlyone person remembered that I had been valedictorian. She was the salutatorianand she introduced me to her husband as follows: "I'd like you to meet RussCloer. He's the one who beat me out for valedictorian!" And then, by wayof explanation, she added: "They always chose a boy in those days."

When I registered, I was asked in which College of theUniversity I wanted to enroll. I told the advisor. " I want to be a MechanicalEngineer." She said, "There is no way we can admit you to the College ofEngineering. You're lacking too many prerequisites. In fact, we are makingan exception in admitting you at all, only because your high school gradesare so good."

"What is the closest you can give me?" I asked. And shesaid, "I can admit you to the College of Arts and Sciences, with a majorin physics and a minor in math." So that's what I did. She suggested thealternative of going back to high school for a post graduate year to getthe needed prerequisites, but the scholarship would not carry over so I couldn'tdo that.

I started at Rutgers in September 1939. The scholarshipcovered only tuition and fees, not room, board and books. So I commuted thefirst year, lived in an inexpensive rooming house for the second and thirdyears and in a college dorm for my last year. I worked part time during theschool year in the College bookstore, as a typist in the Personnel office,as an usher at football games, as a free lance typist and as a Physics labassistant. I worked summers as a YMCA camp counselor, for the college bookstore,and in the Assembly Department of the Western Electric Company. These jobs,along with a what help my parents could afford, paid for my books, room andboard.

My jobs paid only minimum wage, which at that time was40 cents/hour. But the tuition and fees of $330/year were covered by thescholarship. Room and board of about $350/year is what I had to earn.

Rutgers was a land grant college, which required all physicallyfit male students to take two years of basic ROTC. (Military Science andTactics). Fifty students would be chosen from among those who volunteeredfor Advanced ROTC. Those who completed the four years of ROTC would go toa 6 week summer camp for field training between the 3rd and 4th years andwould be commissioned 2nd Lieutenants in the Reserve at graduation. Eachweek, there were three hours of class room work and two hours of close orderdrill, in uniform. (3 credits/semester). The Rutgers ROTC staff was Infantryonly at that time, but we were told that we would be allowed to choose ourarm of the Army when we graduated. A reserve commission in ordnance or signalcorps appeared attractive to me because of their utilization of engineers.I volunteered for Advanced ROTC and was accepted. There were no financialawards offered for ROTC at that time, but we did get one complete officer'suniform, tailor made.

When War was declared, the rules were changed, one at atime:

1. The six week summer camp was abolished.

2. Instead, we would have to go through Infantry OCS (OfficerCandidate School) upon graduation, and those who made it would then becommissioned. Those who didn't, would be sent to Infantry Replacement TrainingCenters with the rank of Corporal.

3. We could no longer choose our Arm of the Army. We wereneeded in Infantry. We were pressured to volunteer for the ERC (enlistedreserve corps) and we would go on active duty on campus as Infantry privatesfor the last semester, then be ordered to Infantry OCS.

4. Anyone that did not volunteer for the ERC would be droppedfrom the ROTC program upon graduation and would have to register with hisdraft board at that time. (Not previously required because we were consideredReservists.)

Spending the last semester as an Infantry Private on campusmade no sense to me, so I was one of five Advanced ROTC seniors (out of 50)who declined to volunteer for the ERC. We five spent the last semester ascivilian members of the ROTC. The other 45 were privates in the Army, assignedto a barracks in one of the dorms, and fed in a section of the college cafeteriaset aside as a mess hall. They couldn't leave campus without a pass signedby the ROTC Major. Just before graduation, we 5 were asked again to jointhe ERC. If we joined now, we would receive orders to report to Ft. BenningInfantry OCS along with the other members of our ROTC class. If we did notvolunteer for this alternative, we would be dropped from the program andwould be required by law to register with our respective draft boards. Twoof the five, including me, signed on and reported to Fort Benning with therest of our ROTC class. The other 3, to the best of my knowledge, never servedin the military. Of the 21 Rutgers 1943 ROTC graduates who were commissioned2nd Lieutenants, Infantry, on September 20, 1943, eleven were killed in actionby War's end.

I entered the Army 6/15/43 after4 yrs of Infantry ROTC at Rutgers University, New Brunswick, N.J.

WWII Infantry OCS, (Officer Candidate School),at Ft. Benning, Georgia, was a 13 week training program turning out Infantry2nd Lieutenants at the rate of 140/day. Those graduates who did not measureup to expectations when later assigned to units, were disparagingly referredto by their men as "90 Day Wonders", due in part to the limited durationof their training.

I reported to OCS Class #298 on June 15,1943, along with thirty of my classmates who had volunteered for InfantryOCS after four years of ROTC at a land grant college. I was in civilian clothesand it was my first day in the army. Ninety-seven day later, twenty-one ofus from my college ROTC class were commissioned 2nd Lieutenants, Infantry.By War's end, eleven of the twenty-one had been killed in action. I haveno way of knowing how many of the rest of class #298 were lost in the War,but I have no reason to believe that the same 52% loss rate did notprevail.

I remember OCS as being one of the most intenseepisodes of my life, aside from infantry combat, which of course was whatit prepared us for. Our determination to successfully complete the programwas the primary goal of our young lives. Our TO (Tactical Officer) jotteddown notes about our performance in his little black book, but we were nevertold how we were doing. Those of us that he decided couldn't hack it wereordered to report to the orderly room, without explanation, at the end ofthe next daily morning formation. When we returned to the barracks at theend of the day, the space on the floor where their cot and foot locker hadbeen was bare. It was quite motivational!

I remember running the uphill bayonet courseunder the hot Georgia sun in mid-July. Bayoneting straw dummies or breakingtheir heads with a "horizontal butt stroke." I remember following a compassheading in the middle of the night through three miles of pitch black woods,while falling into ravines and avoiding simulated enemy lurking in the dark.And qualifying with every infantry weapon on its respective range.

I remember believing that the 37 mm anti-tankgun would penetrate the armor of a German tank. And I remember my first 60mm mortar round overshooting the target by 150 yards. Then correcting rangeand direction to see the 4x6 foot orange canvas target disappear in the smokeof the second round's impact. I crawled under double apron barbed wire carryingan LMG on my forearms, with live machine gun fire four feet overhead. Whilehidden school cadre threw OD pineapple grenades at us with their safety spoonsgone and 4 second fuses hissing. We didn't know that the bursting chargehad been removed, but exploding 1/4 lb. blocks of buried TNT added sufficientrealism. I remember running the obstacle course against a stop watch withthe TO yelling FASTER, FASTER! And swinging hand over hand across theChattahoochee River on a rope stretched between the banks. Running the villagefighting course, firing our rifles at pop up targets in doors and windows.Being ambushed in a ravine by live overhead machine gun fire which tore upthe opposite bank and seeing the student leader of our patrol sit on theground and cry. (He was gone next morning!) Marching back into the companyarea at the end of each day, exhausted in our sweat soaked green coveralls,but maintaining perfect formation at quick step march, with heads held highwhile loudly singing, "I've Got Sixpence."

And how well I remember my college ROTC andOCS buddies, Cox, Dupuis, Everett, Hutcheon, Lipphardt, Pangburn, Potzer,Schweiker, Stavros, Thompson, and Young. They too earned their gold bars,but they never came back from Italy, France, Germany and Okinawa.

I think the Army did a good job with InfantryOCS. The program was carefully planned, well implemented by a trained schoolcadre and managed by a capable staff of officers. The emphasis was alwayson leadership skills, consistent with the OCS motto, "Follow Me." It instilledin the officer candidates an intense need to destroy the enemy and to carefor their men. The result was not perfection, but it provided the best possibleleadership training in the short time available, while weeding out the unfitand developing good leadership qualities in those who showed promise. Myclass started with 200 men and 140 infantry second lieutenants were commissioned97 days later. And as best I can remember, a new class started every day.(Overlapping).

Three months after graduating from OCS, Ishipped out as an overseas replacement and was assigned to the Division thatsaw the most combat of any Division in the U. S. Army (3rd Infantry Division,7th Infantry Regiment) on the Anzio Beachhead in Italy. And to the best ofmy knowledge, I was never referred to as a "90 Day Wonder."

And yet the term "90 Day Wonder," disparagingthough it was intended to be by some, is really quite accurate when takenliterally. When our country was suddenly attacked on two fronts by massiveforces of tyranny, we were far from ready to defend ourselves and other freepeople of the world against this treachery. But the American people reactedswiftly and Infantry OCS was but one of many such programs of selection andtraining which made it possible for us to defeat the best armed, best trainedand most experienced armed forces in the world at that time. We could havedone even better with more time, but there was no more time. Schoolboys whoseexperience was limited to the Boy Scouts and high school sports rose to thechallenge and became leaders of men in a life or death struggle. And theresults of that effort and sacrifice, which was truly a "Wonder," is nowa matter of recorded history. I was a "90 Day Wonder" and I say that withpride!

I met lots of people and made many friendsduring my army years in WWII. But they weren't friends in the way that wethink of friends in civilian life. These were fleeting rather than lastingrelationships. Perhaps a more fitting term would be buddies. Some might evenuse the word comrades, but that seems too stilted, like something out ofa WWI novel. These friends were a port in a violent storm, an oasis on anendless desert of boredom, an island on a sea of loneliness and apprehension.They were someone to lean on, with whom to share the misery and uncertainty,or just kindred souls who briefly filled the lonesome void.

"Hey, soldier, where ya from?" These areamong the saddest words I know, the words of a lonely, homesick soldier.He reaches out for a buddy who will ease the terrible loneliness with talkof home. These friendships might last for only a minute or two, for a day,or at most a few weeks, before the soldiers are sent their separate ways.The one thing they had in common was that once they parted, they rarely saweach other again.

I met John Rahill when we dumped our gearon adjacent cots at Ft. Meade, Maryland. I'd been in the Army for just sixmonths. We were on the second floor of a barracks at the overseas replacementcenter. We shared the dubious distinction of being infantry replacement 2ndLieutenants, headed we knew not where. Rahill had been plucked from the 10thMountain Division in Colorado. I had been sent from the 13th Airborne Divisionin North Carolina. In neither case did we know why we were chosen, wherewe were headed, nor what the future held.

"Hey Lieutenant, where ya from?" we discoveredthat our homes were both in New Jersey, in towns only 20 miles apart. Rahillwas tall and rangy and had played football at Caldwell High School. I hadbeen captain of the track team at Roselle Park High School. We got alongwell and a tentative bond began to develop. As we went through our overseasprocessing, we joked with each other, with forced bravado, as we reaffirmedthe beneficiaries of our G.I. life insurance and made out our last will andtestament. All at the age of 22.

On a January night in 1944, we boarded atroop transport carrying a cargo of 5,000 replacement infantrymen out ofNewport News, Virginia. Each of us felt alone. Rahill and I made a pointof finding bunks in the same compartment in the hold. As we zig-zagged ourway across the Atlantic to Casablanca, we gave a lot of private thought towhat probably lay ahead. Foremost in our thinking was our determination tooverride our fears and carry out our responsibilities honorably, as we hadbeen trained to do. "Follow me" was the motto of Infantry Officer CandidateSchool and we both knew what that meant. Between these periods of direintrospection, we swapped paper back books and forced ourselves to make cheerfulconversation. Upon arrival in Casablanca, we were trucked to a tent studdedreplacement depot outside the city where we found bunks in the same eightman pyramidal tent. Rahill and I ignored the restriction to camp and wentthrough a well worn hole in the fence after dark. Having seen the hit movieCasablanca, we hitchhiked into the city to see the real thing. We felt anurgent need to make the most of the time left us.

Next morning, about 1,000 of us boarded along freight train composed of ancient 40 and 8's. (Freight cars with a capacityof 40 men or 8 horses). Rahill and I disregarded our car assignments andboarded the same box car for the three day trip across the Sahara Desertto Oran. Then, after a few days in yet another tent city, we boarded a smallBritish steamer headed for Naples. We were part of a priority shipment ofreplacement infantry lieutenants urgently needed in Italy. Once again wewere restricted, this time to the replacement depot at a race track northof Naples. Ignoring the order, we took off next morning and hitchhiked toPompeii where we toured the ruins of that historic civilization. (What couldthe Army do to us? Send us overseas?)

A few days later, I was ordered to reportto the 7th Infantry on the Anzio Beachhead and I boarded my LST for the overnighttrip. I vividly remember trudging up the ramp and seeing large white lettersover the gaping entry maw which read, "GATEWAY TO GLORY." (A patriotic gesture?Or a swabby's gallows humor?) I was alone now. My buddy Rahill did not yethave an assignment. We parted at the "repple depple" and I never saw himagain.

That might well have been the end of thisstory, but in early 1946, now a civilian, I went to work as an engineer forthe Curtiss-Wright Corporation in their Caldwell, N. J. plant I was in anoffice separated from the next room by a six foot high, wood and frostedglass partition. The next room was occupied by 6 or 8 Engineering Assistants,young college women hired during the War to perform some of the more routineengineering work. One of my co-workers, who had been a draft deferred engineerat Curtiss-Wright throughout the War, entered my office and I said, "HeyGeorge, what's all the laughter about next door? Sounds like they're havinga party."

"Yeah," he grinned, "One of the girls whoworked here during the War came back for a visit and they're reminiscingabout old times. Her name is Clarissa Rahill.

I was suddenly very attentive. Hey soldier,where ya from? I remembered that John Rahill was from Caldwell. Wouldn'tit be great to see him again, to compare the experiences which followed ourseparation in Naples two years ago? We had some reminiscing to do too. Myspirits rose in anticipation.

"Does she have a brother named JohnRahill?"

There was a pause, then George said, "Shedid, but he was killed in action in Italy." Then another pause as Georgeread my reaction. "Did you know him?" he asked somberly? I was stunned! Ishould not have been surprised that he had been KIA knowing the horrendouscasualty rates suffered by Infantry Lieutenants in Italy, but the War wasover, the killing had stopped and this was now. Rahill was my buddy! Thecoincidence of all this information coming together so suddenly at this place,at this time, with Rahill's sister in the next room was mind boggling. Isaid nothing, but George was perceptive and he knew the answer. After a furtherpause he said softly, "Would you like me to introduce you?"

My mind raced. What can I tell her? I wasn'twith him when he died. I don't know where or how he died. Those are the thingsshe would want to know. She's enjoying this moment of happiness. Why dredgeup those painful memories of his death, which time has healed at least inpart? What good could it possibly do? And I said, "No George. Let it rest."He understood and never mentioned it again. But I wonder to this day if Idid the right thing. Hey soldier, where ya from?"

Addendum: 1/3/03

I was able to make contact with John Rahill's family viathe Internet during the past year. His nephew, Major Roger W. Rahill sentme the following article which appeared in the 5/28/02 issue of "Herald Union",which is printed by the "Stars & Stripes" in Germany. I will be 82 yearsold tomorrow. - Russ Cloer

Article honoring Lt. John Grant Rahill, CO BakerCompany, 1/1-179th Infantry, 3 Purple Hearts, Silver Star

***

I was commissioned a 2nd Lieutenantin the Infantry on 9/20/43 at Ft. Benning, Ga. Inf. OCS. Of the Twenty-oneRutgers Class of ‘43 ROTC grads commissioned 9/20/43, Eleven would beKIA in World War Two.

I was assigned to the 13th AirborneDivision, 190th Glider Inf., Ft. Bragg, NC. on 10/10/43. Then I was reassignedto Ft. Meade, MD Overseas Replacement Center about 1/4/44 as replacement2LT.

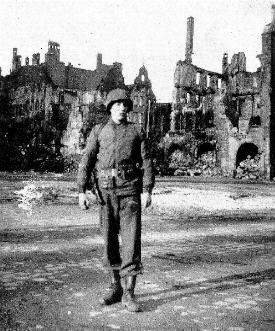

I left Newport News, VA about 1/23/44aboard SS General Horace A. Mann, with 5,000 Infantry replacements. Afterbrief stops at Repple Depples in Casablanca, Oran and Naples, I was assignedto 7th Inf. Reg't, 3rd Inf. Div. on the Anzio Beachhead. I was assigned platoonleader of the Intelligence & Reconnaissance (I&R) platoon out ofHq. Co. late Feb. 1944. Our primary assignment was recon, working out ofRegimental HQ. I led one of the 1st patrols into Rome on 6/4/44.

A photo of me, on the left, in one of my recon jeeps,taken on the Anzio Beachhead in early 1944. The driver's name was LeoPerrault.

I had just turned 23 when I arrived on theAnzio Beachhead, 30 miles south of Rome, and was assigned to the 7th Infantry,3rd Division. It was February 1944 and I was a replacement Infantry Lieutenant.Vivid memories of the combat which followed were etched in my memory forever.At night, the constant rumble and flutter of artillery overhead, theirs andours. The rattle of machine gun fire, ours slow, theirs rapid. The ricochetof brilliant tracers skyward; ours red, theirs green or white. The waveringlight of a parachute flare, lighting the flat and desolate landscape. Thesolid mass of white searchlight beams and red antiaircraft tracers over theharbor during air attack.

Outnumbered by the enemy two to one, withour backs to the sea. The sheer terror of incoming 88 mm fire from a GermanTiger tank. The haunting cry of "Medic!" echoing through the night. And ona rare quiet night, the sound of the Krauts singing Lili Marlene. Bloatedcorpses and black flies. The sickening odor of death. Cold C or K rations.No sleep. Rain. Mud. Trench Foot. Malaria. The incredible loneliness. Thejoy of a letter from home! Sixty-seven days without a change of clothes.Horrendous casualties! More than 100% in the 7th Infantry Regiment plus anequal number lost to malaria and trench foot. Thousands of good men diedthere, three thousand in the 3rd Division alone.

And finally, reinforcements and the "breakout"at dawn on May 23, 1944. My Division lost three thousand men killed or woundedin the first three days. We fought our way through the battered town of Cisternaat night. Fires were everywhere from artillery and white phosphorous mortarfire. We choked on smoke, cordite, and cement dust from the shattered concretebuildings. A Sherman tank supported us, obliterating enemy strong pointswith its 75mm cannon at point blank range. The streets were littered withcorpses lying where they fell, abandoned weapons, destroyed vehicles andcollapsed buildings. This was what Hell must be like.

We fought our way north through the mountainvillages of Cori, Giulianello, Artena, Valmontone, to Pallestrina. The fightingwas savage. We left a scene of desolation behind us, burning tanks and vehicles,dead men and horses bloated in the Italian sun, their eyes and wounds coveredwith swarms of huge black flies, the odor indescribable. Fire, smoke andcollapsed buildings destroyed by tanks, artillery and fire. Abandoned weapons,helmets, ammo and equipment of every description littered the landscape.Columns of Kraut POWs trudged to our rear in shock, helmets and weapons gone,hands clasped above heads bowed in submission. The residue of war.

Twelve days of bitter fighting and on thenight of June 4, 1944, I reported to Colonel Wiley O'Muhundro's dugout, asordered. "Lieutenant, there's a rumor that the Krauts have declared Romean open city and are pulling out. I want you to take a patrol into the cityand find out if it's true. And get back here fast. I'll have the 2nd and3rd Battalions on trucks. I want my Regiment to be the first to enter Rome."I took four jeeps with 50 caliber machine guns and headed toward Rome with 15men. It was pitch dark. Smoke made visibility worse. We passed burning Americantanks and recon vehicles, and dead soldiers along the Appian Way. We metno resistance. We saw nothing alive.

After five miles, we entered the city whichwas ominously silent. No trace of light anywhere. We saw no Krauts, no Americans,no civilians. In the total darkness, we expected to be ambushed at everycorner. It was deathly quiet. Spooky. I had a street map, but I dared showno light to read it. We pressed on but were soon lost amid the narrow windingtunnel-like streets. Until we rounded a bend, entered a huge cobblestonepiazza and there before us stood the Coliseum, silhouetted against the firstblush of pink light in the eastern sky! It was a sight I'll never forget!The thrill of a lifetime! I stood in the midst of 2,000 years of historyand I felt a strong sense of having added to it.

My driver found the way back and I reportedto the CO. "How far into the city did you go," he accused? "As far as theColiseum," I told him. He grinned and ordered the 2nd and 3rd Battalionsin on trucks. Two days later the Allies invaded Normandy. We were no longerfighting alone.

Our decimated Division garrisoned Rome forone week. I visited St. Peters, the Vatican, the Sistine Chapel, the Catacombs,the Aqueducts, the Coliseum, the Forum, a wealth of history. Only one otherLieutenant from my group of twenty-one junior officer replacements, who joinedthe Regiment on the same day, made it to Rome. -- It was good to be alive!

In May of 1944, during the Breakout from the Anzio Beachheadin Italy, the Third Infantry Division suffered twenty-eight hundred battlecasualties in the first three days of the attack. The ancient town of Cisterna,which controlled access to NS Highway 5 (The Appian Way), was the initialobjective. Having taken that objective, the next problem was to move northeastthrough the Alban Hills which surrounded us on three sides. Only in Italywould these be called hills. They reached 3,000 feet and had only a few unpavedroads running EW on which to bring our tanks, artillery and supply vehiclesforward. The entire Beachhead force, some seven Divisions and their supportingunits, took to the few roads available and conditions quickly becamechaotic.

As Platoon Leader of the Intelligence and Reconnaissance(I & R) platoon, I was ordered to patrol to the northeast and reporton road conditions, traffic and the fighting. At dusk, I left the 7th InfantryCP, which would soon be abandoned on the basis of my report on conditionsahead. Before we reached the first rise in the ground, my jeep was stoppedby a line of traffic all trying to move eastward on the single, narrow, unpavedroad to Artena. Field artillery, tanks, antitank guns, engineers, medics,wiremen, and service company trucks carrying ammo, rations, water and gasolinewere parked in a seemingly endless line at the side of the narrow, unpavedroad. I was impressed with the training and discipline of the drivers. Althoughthere was no traffic coming toward us, not one of the hundreds of eastbounddrivers tried to move up by driving on the left side of the road. They allpulled over and turned off their ignition switches. We waited like everyoneelse.

Around midnight, we saw and heard a small airplane witha muffled engine coming toward us from up ahead. As we watched, I could tracethe trail of a Feisler Storch, a German light reconnaissance aircraft similarto our Piper Cub, by following the tiny blue flames from its single engine'sexhaust stacks, a few hundred feet overhead. The Storch was easy to recognizebecause of its two unusually long landing gear struts, which gave it theappearance of a stork in flight, hence the German name Storch. It was flyingvery low, very slow and very quietly. It flew directly above the road headedwest, no doubt counting the tanks, trucks and artillery pieces of the advancingAmerican Army. When it had disappeared from sight, I thought to myself, "He'sgot to come back this way to get to his base. He'll probably come back downthe same road for a second look."

I told my driver to move the jeep about 50 yards into thecleared field on our right and park it. The jeep had a 50-caliber machinegun mounted on a pedestal in the center of the vehicle. I checked to be sureit was ready to fire and that the feed had a full box of ammunition. I thenpointed it at the spot over the road where the Storch was likely to reappear,if he did in fact come back. And I watched and I listened and I waited.

About five to ten minutes later, I began to hear the samemuffled engine noises as before. Then, the blue exhaust stack flame becamevisible. I took careful aim, leading the target by a plane length to compensatefor its forward speed. I fired about 30 rounds while swinging the muzzleto the right. The Storch went into a violent left bank and disappeared inthe darkness. I didn't bring him down, but I may have put some holes in hisairplane and apparently terminated his observation for the night.

Next morning at daybreak, the column began to creep forwardslowly, in fits and starts, as we climbed into the hills. The narrow, unpavedroad, through the wooded hillside, was littered with dead Germans, dead horses,wagons and equipment of every description. (A German Infantry Division atthat time had more horses than men. They were draft horses, not riding horses.)I vividly remember seeing my first German Mark VI Tiger tank up close. Itwas huge! The tracks seemed at least three feet wide and its fearsome 88mmgun, with its characteristic muzzle brake, seemed impossibly long. The tankappeared to have been abandoned at roadside because of mechanical failureor lack of fuel. Those were the only things that could stop the 72-ton MarkVI Tiger with its eight inches of armor plate! After another half mile, thecolumn stopped again and the drivers dutifully pulled over, turned off theirengines and settled in to wait.

Even though only a 2nd Lieutenant at the time, I felt Ishould be doing something to help untangle this mess, but I didn't know what.I was reluctant to go forward, to pass all the stopped drivers doing whatthey had been trained to do. Fortunately, there was no air threat, or wewould have been strafed. Our Air Corps had complete air supremacy. In fact,there was a story going around at that time about a Kraut replacement beingindoctrinated by his sergeant. "Look up," the sergeant said, "always lookup! If you see silver airplanes, they're American. If you see camouflagedairplanes, they're British. If you don't see any airplanes, it's the Luftwaffe."

In Infantry OCS we had been taught to exercise initiativeand to be decisive. "Even a bad decision is better than no decision at all,"we were told. I decided to have my driver take me forward in the left lane,despite standard operating procedure. My objective was not to get a betterplace in line, but to see if there was anything I could possibly do to helpbreak this logjam.

Steele pulled out and we made our way forward past somepretty mean looks from the parked drivers, who were now spending their secondday in line. "Lookit that smart-ass 2nd Lieutenant movin' up to the headof the f---in' line! Who the f--- does he think he is!" One more mile andthe woods ended. There were rolling fields ahead and the sound of heavy rifle,machine gun, and incoming artillery and mortar fire assaulted our ears. Justinside the last patch of trees, two jeeps were parked off the road and twoLt. Colonels were studying a map spread out on the hood of one of the jeeps.Several staff members were standing around at a respectful distance. Smallarms fire crackled overhead. I had Steele park close enough so I could seeand hear what was happening. It became obvious that the column of vehicleshad caught up to the rifle companies and could go no further. One of theColonels was an Infantry Battalion commander agonizing over the fact thathis attacking battalion was being chewed up by the Krauts because he hadno artillery support. The other colonel was the Artillery Battalion commanderwho could offer no help because all of his guns had bogged down in the trafficjam, while attempting to move up within firing distance.

I walked over to the two Colonels, a lowly 2nd Lieutenantwith a single tarnished gold bar, and said, "Sir, I'm Lt. Cloer, 7th InfantryRecon Platoon. If you tell me which artillery unit you want, I'll pull itout of that traffic jam and get it up here." They looked doubtfully at meand each other but their demeanor said, "What have we got to lose?" The artilleryColonel said, "I need any vehicles from the 10th Field Artillery. The gunsare being towed by 1 ½ ton trucks with gun crews and ammo aboard."

Steele and I hurried back down the column. We knew, ofcourse, that the Army used a uniform marking system on its vehicles whichmade it easy to identify the unit to which they belonged. On the front andrear bumpers, the unit designation was stenciled in white on an olive drabbackground, in this case, "3-10 FA," Third Division, 10th Field ArtilleryBattalion. We hurried back down the column, slowing only when we identifieda 10th Field truck. I yelled, "10th Field only, pull out and move to thehead of the column!" Response from the drivers was magnificent! In the firstmile and one half, we sent four trucks forward, towing their 105mm howitzers,complete with gun crews and ammo. We then went forward again, but this timeI got no dirty looks from the drivers still waiting in line.

When we returned to the edge of the woods, the first twoguns were firing. The Artillery Colonel had marked out positions for theremaining two and they too were firing within a few minutes. I felt reallygood about what I had done. Not only was it essential to continuing our advanceon Rome, but it almost certainly saved American lives as well. And nobodyelse had thought of it! Or perhaps they had, but their training, disciplineand the old adage, "Never volunteer," were too ingrained for them to act.It takes a certain amount of guts for a 2nd Lieutenant to walk up to twoLt. Colonels in a critical situation and tell them what they should donext.

The word "Thanks" is not one you hear very often in theArmy, and never by a Lt. Colonel to a 2nd Lieutenant. And I didn't hear itthis time. It just wasn't done. If you did something right, it was considerednothing more than what you had been trained to do. But the Artillery Colonelwalked over to me after the fourth gun was firing and his words still ringin my ears, "Lieutenant, you sure earned your pay today!"

Following the breakout from the Anzio Beachhead on May23, 1944, the 7th Infantry fought its way north through Cisterna di Littoria.By May 27, in hard fighting, we were still pushing north about 1 ½ milesNW of Artena. The Regimental forward Command Post was located in a gullyrecently vacated by the 1st Bn. C.P. It was about 200 yards off the unpavedroad leading to Artena. We had been advised by 1st Bn. that this area wasunder enemy observation and any activity between the ravine and the roadwould bring accurate enemy shellfire into the ravine. Any vehicle which foundit necessary to approach the C.P. in daylight was to stay on the road andturn off at a wooded area which provided a concealed path back to theravine.

As platoon leader of the I & R platoon, I was responsiblefor C.P. security along with my Intelligence and Reconnaissance duties. Iwas also responsible for the movement of enemy POW's from the three Bn. C.P.'s,back to Regiment for interrogation and then on to Division. To this end,I had two of my men assigned to each Bn. Hq. Co. on a rotating basis. Oneof these men was Sam Aldrich, an easy going southerner, always agreeable,always good natured. He smoked an old corn cob pipe, which when not in hismouth, was stuck stem down in the top of his combat boot. He was kiddedunmercifully by the other men because the acrid ‘juice' from the bowlhad to be seeping down into the stem and then into his mouth when he litup. Sam took it all good naturedly and just grinned.

The day before we moved forward into the 1st Bn. C.P.,Sam's partner came back guarding two Kraut POWs with the news that Sam hadbeen hit by 88 mm shell fire, had lost his leg at the knee and had been evacuated.When we moved forward into the former 1st Bn. C.P., one of the first thingsI noticed was a bloody human leg, severed at the knee, lying in the bottomof the ravine. There was an old corncob pipe stuck in the top of the combatboot. It was Sam's leg and I had the men bury it. It was a very soberingexperience.

I had the men dig two man foxholes deep in the sides ofthe ravine and after seeing Sam's leg, they needed no encouragement. Theydug like ferrets! My platoon runner, PFC Bigler, dug a hole for me and himselfat a location I designated. The colonel and his immediate staff moved intoa sandbagged room-size bunker built into the side of the ravine earlier,either by the 1st Bn. or by the Krauts before them.

We hadn't been there long when one of my lookouts announcedthat there was a jeep approaching across the field via the most direct routefrom the road. We had been warned not to use this route in daylight becauseit was under enemy observation. As the jeep drew closer, we could see thatthere were three people in it and there was a one foot square red placardon the front bumper with a large silver star in the middle designating thatone of the occupants was a General. My lookout swore softly. The jeep pulledup to the rim of the ravine, the General scrambled down the steep 25 footslope and headed for the C.P. bunker at a very fast walk. The other two peoplewere his aide, a major, and his driver, a sergeant, Neither of them followedhim into the bunker. They stood in the bottom of the ravine to await hisreturn.

As the jeep approached the rim, I had yelled for my mento take cover in their foxholes. I then waited just long enough to see thatthe General was in fact a General and had entered the C.P. bunker safely.I then ran to my foxhole. My runner, PFC Bigler was already in it. It tookmaybe ten more seconds before the first shell came in. It was terrifying!The 88 mm high velocity, flat trajectory shell travels so fast that the firstsound you hear is the ear-splitting crash of the shell burst. This is followeda fraction of a second later by the fearsome crack of its supersonic flightand then by the soft boom of the muzzle blast a half mile or so away. I wasn'tcounting the shell bursts but there must have been about five and they wereall inside the ravine!

There was then a lull of about 30 or 40 seconds and Biglersaid, "Lt., shouldn't we be checking to see what we can do for the wounded?Nothing was further from my mind! How did we know the 88 was through firing?I waited another 10 seconds and then my sense of duty forced me out of ourhole to check the ravine. All of my men were in their deep foxholes and seemedOK. But the General's aide and his driver had no foxhole. The sergeant wassitting on the floor of the ravine exploring his face with his hands. AsI came up beside him, I saw in profile that he had no face! It was gone,from his eyebrows to his neck! The eyes, the nose, the mouth, the chin, nothingwas left but a bloody red maw which he pawed at, fully conscious and tryingto understand. He was choking from the blood in his throat. What can youdo for a man like that? You feel helpless and frustrated because you knowthere is nothing you can do!

I moved to the major who was lying on his back. He hada bloody hole in the center of his chest, but he too was conscious. Therewas no arterial spurting, but blood was leaking out steadily. He asked forwater. Perhaps he shouldn't have it with a chest wound. But I didn't havethe strength to deny it. After warning him of that, I tilted my canteen andlet an ounce or two drip into his mouth. He asked me to lift his head sohe could swallow it. He couldn't raise his head alone. I did.

About then, a medic showed up from the bunker. He gavethe sergeant a shot of morphine and began wrapping his head in white gauze,from his neck up to the top of his head, round and around and around. Bythis time, the sergeant was unconscious. The Regimental Surgeon now showedup from the bunker. He had called for an ambulance by radio or field telephone.I asked him if he thought the sergeant would "make it," our euphemism for"survive." His answer was a soft, "I hope not." We now found out that oneof my men, Corporal Fennell, had been wounded in his foxhole. A shell fragmentstruck him in the buttocks and went on through to tear up his intestines.

The ambulance, with enormous red crosses on a white background,now came up the road and turned off to cross the same shortcut the Generalhad taken. I thought to myself, "Oh man! Here it comes again!" But he parkedright next to the General's jeep on the lip of the ravine and nothing happened.The three badly wounded men were loaded aboard and he then drove back tothe road and wherever they take wounded men in that condition. The Germangunner didn't fire. I know what the Geneva Convention says about firing onmedical personnel but the rules were observed only sporadically.

I wonder to this day if the General's trip was worth thecost. And whether the German gunner could see the General's ostentatioussilver star on the red plaque through his binoculars. And whether the Generalknew that he should not have approached the C.P. by that route, or if hethought rules don't apply to Generals and besides, if he moved quickly, hecould make it to the bunker before the gunner could fire. He destroyed thelives of three other men making his point, whatever it was.

Later in the day, the Regimental Surgeon asked me if Iwanted a Colt 45 caliber pistol. I was not authorized to wear one. My weaponwas the 30 caliber carbine. But it was a comforting feeling to have thatreserve firepower on your hip and I hastened to say yes. I was to carry itfor the rest of the War. It was only after I noticed the fresh red bloodstains on the top of the brown leather holster that I realized where it camefrom.

In May 1944, an aging 2nd Lieutenant joined the7th Infantry Regiment as a replacement officer on the Anzio Beachhead inItaly. He was in his late thirties and in civilian life he had been a schoolteacher. Because of his age, he was not assigned to a rifle platoon, butrather, was made a Liaison Officer on the Regimental Staff. Lt. White, wasa rather prissy individual and being the junior officer on the staff, hewas singled out as the butt of jokes on those rare occasions when timingand environment made jokes acceptable. Some thought him rather strange becauseof his huge handlebar mustache which he kept waxed and carefully groomedwith the tips curled up into half circles. His small, perfectly round,steel-rimmed G.I. glasses rounded out his bizarre appearance.

Jokes and horseplay were a rare commodity in anInfantry Regiment, what with the maiming and dying that went on daily. Whatlittle humor there was, was of the black variety, as illustrated by BillMauldin's cartoons in the Stars and Stripes, the Army newspaper. They werepertinent, subtle and timely, poking fun at the Army, the rear echelon, officers,and the hardships of the Infantryman's lot. The men regarded Mauldin as oneof their own, which he had been as a private in the 45th Infantry Division.He showed a remarkable insight into the mind of the Combat Infantryman. Thattype of humor, frequently misunderstood or not understood at all by outsiders,gave the men a much needed chuckle and a release from the terrible stressand pressures of War.

"I need a couple guys what don't owe meno money fer a little routine patrol"

After the Anzio breakout and the taking of Rome,the Third Division, decimated by battle casualties, moved from Rome to awooded area near Naples for a few weeks, to take on replacements and to trainfor the amphibious assault on southern France. During one of these trainingexercises, Lieutenant White was assigned as loading officer for a group ofLCTs (Landing Craft, Tank) taking aboard thirty-five ton Sherman tanks. Thefirst LCT pulled up to the dock, bow first, and lowered its ramp onto theconcrete at a twenty-degree angle. There was no convenient bollard to tieup to, so the Navy crew applied forward thrust to hold the LCT against thedock. Lieutenant White, in charge of loading, waved the first tank forward.When the tracks were half on the ramp and half on the dock, the climb provedtoo steep and the engine stalled. The driver restarted, shifted to a lowergear, raced the engine and let out the clutch. The thirty five-ton tank leapedforward, and with the rubber padded steel tracks gripping the concrete dockrather than the slick metal ramp, the tank pushed the LCT away from the dock,continued on, and with an enormous splash, sank in fifteen feet of water.Fortunately, all hatches were open and the tank crew members bobbed to thesurface like so many corks.

The next day, Lt. White was served with a "Statementof Charges," an Army form used to enforce the regulation which held a soldierpersonally responsible for the cost of any piece of government property lost,damaged, or destroyed as a result of the soldier's negligence, or neglect.The form read as follows: "Lt. White is held responsible, as loading officer,for the loss of one (1) Sherman tank due to his negligence during a loadingexercise in the Bay of Naples, Italy. The tank is valued at $75,000. Lt.White is hereby held liable for repayment of this sum to the government ofthe United States. Toward this end, eighty per cent of all pay and allowancesdue or to become due will be withheld from said officer's monthly pay untilsuch time as this debt is satisfied."

Lt.White didn't have to be a mathematical geniusto figure out that eighty percent of $150 per month is $120 or $1440 peryear and it would therefore take him fifty-two years to pay off this debt,assuming no interest charges.

Of course, he knew about Statements of Charges,but they were never used in combat. Soldiers routinely threw away governmentproperty; gas masks, ponchos, camouflage capes, mess kits, ammunition, leggings,and none had ever been served with a statement of charges in combat. Butwe weren't in combat now! We were training in a rear area and many high rankingsticklers for regulations routinely enforced rules in rear areas that thecombat veterans thought unnecessary. Besides, this document was signed bythe Regimental Commander, a West Point full Colonel, a no-nonsense leader,fair but not known to make jokes or even to smile. (Colonel Wiley O'Muhundro).The story spread rapidly while Lt. White worried himself sick. After allowinga few days for the story to complete its rounds, the Colonel told Lt. Whiteit was only a joke and the entire regiment had a morale boosting laugh atthe Lieutenant's expense. The butt of the joke was a member of the RegimentalStaff, not a front line soldier, and he was a junior officer besides, whichmade the joke all the more enjoyable for the dogfaces. And the Colonel cameout of it with recognition that he was a regular guy, a human being afterall. The affair had a salutary effect on morale just when it was needed most,on the eve of a bloody amphibious assault landing in Southern France.

We made the D Day landing in Southern France atH+40 minutes near St. Tropez.

D Day - SouthernFrance - 0800 - August 15, 1944

When the victorious 3rd Division marched into Romeon June 5, 1944, it was decimated after four months of vicious fighting onthe Anzio Beachhead and the breakout to Rome. In those four months it hadsuffered 9616 battle casualties (killed, wounded or missing) and 13,238non-battle casualties (mostly trench foot and malaria). (Ref. Division History.)Many of the survivors were inexperienced replacements or hospital returneeswho were still on the mend. Average Division strength during that periodwas about 10,000 men which meant that the replacement rate was 230%!

The Division was given one week of R & R inRome, then trucked to a wooded area north of Naples (near the town of Pozzuoli)to integrate replacements and to train for an assault amphibious landing.It would be on the coast of Southern France, although we were not told thelocation nor timing for security reasons. We slept in tents, washed in outdoorshowers and ate hot food in an outdoor chow line. And we took an Atabrinepill every day to suppress the symptoms of malaria with which most of ushad been infected in the Pontine Marshes on the Anzio Beachhead. There wasa curious procedure for this. Since some soldiers apparently preferred malariato infantry combat, an officer stood at the head of each chow line with acan of pills. As each soldier went by, he opened his mouth, the officer insertedthe Atabrine pill on his tongue, and the soldier then took a swallow of waterfrom his aluminum canteen cup. The officer was responsible to see to it thateach man swallowed his pill. Once back in combat, the Atabrine pillsdisappeared.

On the other end of the chow line there were threelarge garbage cans. The first was for any food left over after the soldierfinished eating. The second was hot soapy water in which he swished his emptymess kit to clean it and the third was very hot clear water to remove anysoap and sterilize the mess kit. In Italy, there were usually a half dozenragged Italian kids, each holding an empty gallon can that the kitchen crewhad disposed of, begging for scraps of food before the soldier emptied hismess kit into the garbage can. Two rather famous cartoons came out of this.Bill Mauldin shows "Willie" in his combat regalia, holding his full messkit while a ragged little girl with an empty gallon can looks up at himhopefully. The caption is "The Prince and the Pauper." The other was, I think,a "Sad Sack" cartoon. The first frame shows a similar scene. But the followingframes show the little girl carrying her full can home and dumping it intothe hog slop behind her house.

We had excellent maps and an accurate 20 foot sandtable model of Red 1 beach on which we would land near Cavalaire-sur-Mer.There were detailed lectures on what we could be expected to encounter andhow to cope with the defenses. We practiced endlessly loading and debarkingfrom our landing craft, LST's, LCT's, LCI's and LCVP's. The landing craftwere not noted for their speed. (There was a joke, popular at the time. Howfast is an LST? It actually has four speeds. Ahead slow, reverse, full aheadand flank speed. Each of these is about six knots!)

The Generals gave us pep talks on how weak the enemyopposition would be and on the overwhelming strength of our Navy and AirCorps support. The chaplains were kept busy leading us in prayer and theattendance at services grew as the date of departure approached. Of course,the date and location were kept secret, but we knew we were getting closewhen a concertina barbed wire stockade was erected in the Regimental areaand about 50 GIs, who were potential AWOL suspects, were confined underarmed guard until they could be loaded aboard ship. Business picked up atthe Aid Stations as a rash of self inflicted gunshot wounds broke out. Mostclaimed to have shot themselves in the foot while cleaning their weapon.We were issued gas masks and told to discard them once ashore if there wasno gas. Service personnel would pick them up later. It's the only time throughoutthe War that I remember having to carry a gas mask except for the trip overseasand then we turned them in at the replacement depot before being assignedto a unit.

Shortly thereafter, we were told to pack up andwe were trucked to the docks in Naples. The Italian civilians told us wewere headed for Southern France, not the Balkans as some suspected. Thatwas fine with me because I spoke French fluently at that time. No word fromour superiors until we were told to turn in all our Italian Occupation Lirein exchange for Occupation French Francs. (Two for one.) A Lire was worth1 cent American, a Franc 2 cents American. Possession of American money wasillegal. We were assigned to landing craft and we climbed aboard. My companyof approximately 150 men was assigned to an LCI (landing craft infantry).The medium sized LCI had a pointed nose, but narrow ramps on either sideof the prow which could be dropped on the beach to exit. As we slowly drewaway from Naples and out to sea on August 9, 1944, I remember looking backover the fantail at the thin trail of smoke rising from Mt. Vesuvius andwondered who would and who would not survive this one.

We had been told that the convoy was enormous;battleships, aircraft carriers, cruisers, destroyers and more landing craftthan were landed in Normandy on June 6. But the convoy was so spread outthat we could only see four or five ships from our position through the thinhaze and smoke. Six days after leaving Naples, the convoy arrived off thebeaches between Cavalaire-sur-Mer and St. Tropez. The assault was made bythree Infantry Divisions, the 3rd, 45th and 36th, all of which had compiledstellar combat records in Italy and Sicily. Naval guns saturated the shorelinebefore H Hour which was 0800. Return fire, both artillery and small armswas lighter than expected. But there were mines and tetrahedrons in the shallowwater and three of my Division's LCI's were blown up with a loss of 60 menMissing In Action. This caused some changes in plans and my platoon, whichwas scheduled to hit the beach at Hour + 40 minutes, was held up for almostan hour.

D Day Southern France, 0800, 8/15/44

(Smoke covered beach from LCI ramp)

We watched as the small LCVP's circled until allwere present for a given wave and then they separated and headed for thebeach in a more or less straight line parallel to the shore. This tacticavoided concentrations of men and landing craft which would have made theenemy's job easier. Shellfire from our Navy's big guns rumbled overhead.Nearby were flat bottom LCT's whooshing off rockets row after row with terrifyingscreams as each rack went off. Small Navy ships (destroyers?) equipped withsmoke generators raced back and forth along the beach. The beach was coveredwith smoke so the Krauts couldn't see what was coming at them.

A rope cargo net was thrown over the side of ourLCI and one of the smaller LCVP's (landing craft, vehicle, personnel) camealongside. Because of LCI losses to mines, a change of plans had been made.We clambered down the rope cargo net which had been thrown over the sideof our LCI (hold the verticals dummy, or your hands will be stepped on!)and jumped into a small LCVP which was bobbing up and down below us. Onceaboard, we joined the circle, became a line parallel to the beach and thenour wave went in.

I stood up front right behind the raised loadingramp and my 35 man platoon crowded in behind me. Enemy mortar, artilleryand rocket fire caused water spouts which we could see above the high sidesof our LCVP and small arms fire crackled overhead. We couldn't see the beach.The front and sides of the LCVP were too high. I saw no fear shown by anyone.Nor enthusiasm. We had a job to do, we had been trained to do it and Armydiscipline took over. Military discipline is a hard thing to explain. Weknew what was expected of us and we would do it to the best of our abilityregardless of the dangers. We had stopped independent thought when we boardedthe LCVP. Our minds went into a different mode. Our actions were programmedand we would follow the script.

D Day Southern France

88 mm gun on beach

My first surprise was that the Navy Coxswain ranthe LCVP right up on the beach, dropped the ramp and I stepped off onto drysand! Didn't even get my feet wet! This was very unusual because of the Navy'sfear of mines in shallow water. We had been trained to "GET OFF THE BEACH!"because that's where the mortar and shellfire was falling. So I ran forwardwith a loud "Follow Me" and found that the 50 yard wide strip of trees betweenthe coast road and the sand, unlike our sand table model, had all been felledtoward the water, creating an almost impassable barrier! I got my 3rd surprisewhen I looked back for the first time and saw my men in single file, joggingafter me in my footprints! If someone was going to step on a mine, let itbe the Lieutenant! Some of these men had made as many as five previous landingsunder fire, Casablanca, Sicily; Salerno, Italy and Anzio. I quickly founda passage through the felled trees that someone had gone through before andtherefore seemed less likely to be mined or trip wired. We took up firingpositions along the slope of the slightly elevated coast road with one ofthe rifle companies.

Resistance at this stage was surprisingly light.Instead of a solid wall of concrete bunkers like those encountered in Normandy,we met only scattered small arms fire and intermittent artillery and mortarfire on the beaches. There were a few 88 mm guns in log surrounded emplacements,but it appeared that the crews had fired a few shots at the landing forceand then fled. The POW's we took fitted the mold we had been told to expect.Lots of older men and young boys with a large percentage of Russian and Polishvolunteers who had apparently accepted this assignment in lieu of forcedlabor in German POW camps. And one fairly large group of German soldiersthat I saw, had small rectangular black mustaches under their noses, justlike Adolph Hitler's. It was not apparent whether they were doing thisvoluntarily as a show of support for the Nazi cause, or whether they hadgrown the mustache under orders from their superior officers. By the timemy platoon landed, about an hour after the first wave, the beach area hadbeen pretty well cleared of enemy resistance by our Battle Patrol. Despitethe lighter than expected resistance, my Regiment lost 58 men KIA and about250 WIA. Many of these were from mines rather than aimed fire. The 3rd Divisiontook 1627 enemy POWs on D Day.

The stiffest resistance was met at Cape Cavalaire,a promontory jutting out into the sea and capped with artillery, mortarsand machine guns covering the landing beaches. This was similar to PointDu Hoc in Normandy. The relatively light casualties in the 7th Infantry intaking this vital strong point, were largely due to the bravery of one man,Sergeant James Connor of the Battle Patrol. Conner was knocked down and seriouslywounded in the neck by the same hanging mine that killed his platoon leader.Refusing aid, he urged his men across several hundred yards of mined beachunder heavy fire from mortar, 20 mm flak guns, machine gun and rifle fire.Taking over as platoon leader, Sergeant Connor inspired his men forward.He received a second painful wound which lacerated his neck and back, buthe refused evacuation and impelled his men to assault the enemy gun positionson the hilltop. His third grave wound, this one in the leg, felled him inhis tracks, but still he urged his men on from the prone position. Less than1/3 of his original 36 man platoon remained, but they took the enemy position,killing 7 and capturing 40 of the entrenched enemy. They stopped all enemyfire on the landing beach from this vantage point. Sergeant Conner was awardedthe Medal of Honor.

The principal mission of my platoon the first daywas to move about a half mile inland, establish and secure a new RegimentalC.P. ashore and to assist the rifle platoons in the guarding and evacuationof the many POW's by loading them aboard returning LCVP's. Engineers sweptthe beach for mines and marked cleared paths after which our vehicles startedto come ashore.

We moved inland rapidly against relatively lightresistance. We were told that a radio intercept had ordered the Krauts todelay their counterattack until they were out of range of our naval gunfire.D-Day objectives were achieved by noon of the first day. Our vehicles cameashore and we moved rapidly northeast toward Avignon and the Rhone RiverValley which was the primary road, railroad and river route north towardBesancon, Montelimar and the Belfort Gap. My recon platoon was on the movealmost continuously, feeling out the next defensive stand of the fleeingenemy. We were overwhelmed with Kraut POW's, many of whom seemed glad tohave the opportunity to surrender to the Americans. When one of my reconjeeps with four men was late getting back from what I thought was an easymission, I went looking for them in another jeep. I found them eating ripemelons at the side of a road which bordered a huge melon field. The weatherwas beautiful and you would think they were on a picnic!

We bypassed the ports of Marseilles and Toulonand left the mop up of enemy, who were now completely cut off from retreat,to the French forces which had landed on our left. The town of Montelimarwas a key early objectives because it controlled the entrance to the RhoneValley passage north. This escape route was choked off early by our artillery,infantry and air force and the retreating enemy forces were trapped betweenour attack and the Rhone River. Twelve miles of roadway was covered withthousands of dead horses, smashed carts, burned out vehicles and blackenedcorpses. It later served as an introduction to War for replacements cominginto Marseille and moving up to join us in the Vosges Mountains and the ColmarPocket. At that time, August 1944, the Germans had more horses in an InfantryDivision than they had men. These were draft horses pulling carts, wagons,and artillery pieces. There were some vehicles, but the Germans were criticallyshort of gasoline and diesel fuel. Many of the military vehicles and mostof the confiscated civilian vehicles were run by charcoal burners which pipeda combustible gas to the engine. What little fuel was available was apparentlysaved for tanks and aircraft.

Montelimar, France - August 1944

(Remains of German 19th Army fleeingnorth.)

We fought our way north against relatively lightresistance in what the G.I.s called the Champagne Campaign. Little did werealize what bitter fighting lay ahead in the Vosges Mountains and the ColmarPocket.

(There are German soldiers in thecellar!)

Another jeep Recon patrol in Southern Franceon a beautiful Indian summer day in 1944, this time to find a suitable locationfor the forward displacement of the Regimental CP. I took all four of myjeeps and fifteen men, since we carefully marked the route for others tofollow, eliminating the need to go back. There were no front lines, as such.The Krauts were slowly withdrawing to the north, stopping only to defendfavorable terrain. The situation was "fluid" which means in this case thatneither side knew for sure where the enemy was.

We drove through a small French town to thecontinuous ringing of church bells. French civilians of every age and descriptionlined the road, cheering, throwing flowers, offering wine and fruit, manycrying with joy after four years of brutal occupation. A very pretty youngwoman danced up to our jeep on the driver's side. Steele braked to a stop,and she gave him a big hug and a kiss. I was riding in the front passengerseat. She leaned forward between Steele and the steering wheel and was aboutto give me a kiss too, when she suddenly recoiled and backed away into thecrowd. I couldn't imagine what I had done to cause this reaction. I turnedto Steele and said, "What do you suppose that was all about?" He gave mea salacious grin and said, "I squeezed her titty!" I said, "Steele, you maybe the best jeep driver in the company, but you're no gentleman." To whichhe replied, "You got that right, Lootenant."

I found a large chateau in late afternoonin the area that the Colonel had designated on his map. I reserved the mainhouse for the War Room, the Colonel and his staff. There were a number ofsmall workers' cottages on the land and after setting up defensive positionsaround the CP, I occupied the northern most cottage with Steele and my platoonrunner, Bigler. The house was on the side of a hill abutting a small lakewhich was surrounded by trees. The rest of my patrol moved into other isolatedworker's cottages within a few hundred yards.

I enjoyed conversing with the farm workerand his wife in their language. My four years of French language study servedme well. It was almost dusk and they invited the three of us to have dinnerwith them. We offered to share our C rations, much to their delight. Thewoman went down the cellar stairway to get some potatoes and several minuteslater returned with an apron full. But her face was as white as a sheet!She whispered in my ear, "Il-y-a des Boches en bas!" "Combien?" I asked."A-peu-pres douze!" "Est-que-ils a des fusils?" "Oui, beaucoup de fusils!"She was telling me that there were twelve armed German soldiers in the cellar!

I acted reflexively. "Bigler, cover the cellardoor with your Thompson. Steele, round up as many men as you can find quickly,including Nessman with his machine gun. I'll cover the cellar door and windowsfrom outside. Move!" In a few minutes we were in position. It was almostdark. Corporal Nessman was fluent in German and I had him shout at the outsidecellar door, "We know you are in there. Drop your weapons and come out withyour hands up." No response! Could the woman have been mistaken? Not likely.Once more, in German, "Kommen sie hier mit der hande hoch, Raus!, Schnelle!,or grenades are coming in through the door and windows!"

After a brief hesitation, we heard shufflingnoises and then "Kamerade!" the standard Kraut expression for surrender.Three Krauts came out with their hands clasped overhead. Where were the othernine? The lead Kraut then told Nessman that their sergeant, having seen usenter the area, hid them in the cellar and was waiting for dark to escape.When the French woman entered the cellar, they held her as long as possiblewithout alerting us to their presence, then went out the window nearest thewoods. Three decided to give up and lagged behind. I checked out the cellarand the rest were gone.

They could just as easily have crept upthe cellar stairs and killed the three of us before we realized we were indanger and then made their escape through the woods. They had rapid firemachine pistols, while our weapons were stacked in a corner, except for the45 caliber pistol on my belt. In retrospect, I think they may have been aRecon patrol like us, with orders to get information but to shoot only iffired upon. Or possibly, they were a combat patrol left behind to shoot upwhat was a likely command post location. But after seeing the four jeepswith 50 caliber machine guns, they decided that their chances of escape werebetter if they didn't start a firefight.

My earliest recollection of a motorcycle goes allthe way back to 1925 when I was four years old. My parents, my sister andI lived in a second floor apartment in Jersey City, New Jersey. We had nocar, but my father owned a red Indian motorcycle with a side-car which hekept in a nearby rented garage. On a pleasant Sunday, my mother would sometimessay, "Let's take a ride up to Sussex County for a breath of fresh air." Myfather would get the motorcycle while my mother fixed a picnic lunch andoff we would go to spend the day in what was then sparsely populated farmcountry. In winter, my father removed the engine and transmission and storedthem under his bed when he wasn't overhauling them on the kitchen table.

So, not surprisingly, my first ride on a motorcyclewas a very memorable event. It took place in France in 1944. I was platoonleader of the 7th Infantry I & R platoon and I spoke French quite fluentlyat that time. We had just liberated another French farming village and thevillagers crowded the roadside to offer us hugs, kisses, fruit and wine.But one old farmer heard me speaking his language and came over to my jeepto begin jabbering away, as the French were wont to do. He had a greatergift to offer. He told me that the Germans had left behind a motorcycle inapparently good condition, because they had run out of gasoline, a constantproblem for them. He had put it in his barn with the intention of turningit over to the Americans. We had a policy of not using enemy vehicles becausewe had enough of our own and to drive Kraut equipment was an invitation todeath by "friendly fire." Besides, we had an image to maintain. We were anadvancing American Army, not a bunch of gypsies!

But there is a certain mystique about motorcycles.My curiosity and pleasant memories of the old Indian demanded that I at leastgo look at the German machine. I told the farmer to climb in the back ofthe jeep and he guided us to his barn. I wheeled out the huge BMW (BavarianMotor Works) machine and was fascinated by it! It radiated raw power andsuperb German workmanship. It was painted in the Wehrmacht light earth/darkearth flat camouflage colors and it was beautiful! I turned to my jeep driver."Steele, how about getting that spare jerry can of gas off the back of thejeep and let's see if we can start this monster." We filled the tank, I turnedon the ignition, kicked the starter crank, and was rewarded with the throatyroar of the engine. It was sweet music to my ears and my spine tingled. Ifamiliarized myself with the controls. The temptation to ride it was justtoo great.

I had never ridden a motorcycle before, but I convincedmyself in no time at all, that years of experience on a bicycle were sufficienttraining. I shifted to low gear and sedately cruised out of the drivewayand onto the paved road. For the next half hour, I rode serenely throughthe beautiful French countryside at a leisurely pace. The feeling ofexhilaration, the joy of the wind in my face, the sensation of controllingsuch power, and the complete sense of freedom I felt is indescribable. Itwas truly a one of a kind experience.

I took a different route on the way back and soonfound myself on an unpaved road. I drove slowly and carefully, but as I leanedinto one curve, the wheels slid out from under me and I found myself slidingdown the road on my hands and knees at about 20 MPH. I picked myself up andsat at the edge of the deserted roadside for five or ten minutes and examinedmy scrapes, cuts and bruises while the shock wore off. The knees were gonefrom my wool O.D. trousers and both knees were raw and bloody. But my handswere worse. Both palms were lacerated and bleeding. The BMW was lying onits side, stalled out, but apparently no worse for wear. I cursed it soundly,stood it up and climbed back on. No piece of Kraut equipment was going toget the better of me! I started it up and the engine responded with a smoothmusical burble which I took as a welcome apology. I drove back to the barnand told the farmer to hold onto the Hog and give it to the rear echelontroops which would follow us. Only then did I stop at the aid station tohave the cuts and abrasions cleaned and sterilized.

But by far the worst part of the experience, wasfacing the men of my platoon. The story had traveled like lightning, andalthough no one said a word, I knew what they were all thinking. "How thehell could the Lieutenant do such a damn-fool thing? We would never havefallen off!" But we moved out the next morning, the lacerations healed andthe motorcycle adventure was history.

I never rode a motorcycle again. The closest I camewas on a Bermuda vacation, forty years later, when my wife and I rented Hondamopeds to tour the island. The moped was a far cry from the BMW and doesn'teven count as a motorcycle. But I do remember passing a teen age native onhis beat up moped. As I breezed by, he shouted after me, "GO, GRANDPA,GO!"

From Maxonchamp, the 7th Infantry clearedRemiremont and pressed on toward Vagney, France and the Vosges Mountains.In early October 1944, our CP was established in a large two story stonehouse in an open field on the edge of Vagney. A two-lane road on our leftled into the center of town. To the left of the road was heavily wooded highground. Fighting had been heavy and we hadn't moved in several days.

Early one morning, I was ordered to lead a small patrol into the center of town and check the condition of the 1st Battalion CP, since all communication had gone out during the night. This was vitally important because with no communication from the Battalion CP, the rifle companies had no direction and Regiment and the Field Artillery could provide no support. I was also ordered to be on the lookout for "stragglers," a term used to describe men who had become separated from their company, for one reason or another, and were in no hurry to get back. Some were careful to not go far enough to the rear to be considered deserters, just close enough to be able to claim that they were trying to find their way back. They wanted a few days to collect their senses. Thankfully, I wasn't called upon to do this very often because I hated it. It was a Military Police function but there were no MPs this close to the rifle companies.